In early February, Curatorial Assistant Ingrid Langston and IFA MA Candidate Ashley McNelis toured the MoMA galleries. Langston assisted MoMA PS1 Curator Peter Eleey in organizing the exhibition Sturtevant: Double Trouble at MoMA, which runs from November 9, 2014 to February 22, 2015. Double Trouble is timely not just in light of the artist’s recent passing, but also because it is only Sturtevant’s second American-organized solo show since the 1970s. The intervening four decades—in which Sturtevant was largely ignored by the art world—have afforded her audience the time and hindsight to catch up with her intelligently penetrating vision. Sturtevant: Double Trouble also juxtaposes traditional art historical narratives (represented by works in MoMA’s permanent collection) against works from Sturtevant’s reactionary oeuvre. The exhibition will be on view in the third floor Special Exhibitions Gallery and the fifth floor Sue and Edgar Wachenheim III Painting and Sculpture Gallery at MoMA until it heads to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles from March 21 to July 27, 2015.

Ashley McNelis: I understand that Sturtevant actively combated the use of curatorial strategies at other institutions. What was working with her at MoMA like?

Ingrid Langston: Unfortunately, I never got to meet her personally. She was working with Peter Eleey closely and was planning to come out for the installation before she passed away in May 2014. Peter went to Paris every few months to meet with her, but by the time I came on the project she was not really traveling much. So I never worked with her directly, which is a shame, but probably also made my life a lot easier. We did work closely with her daughter, Loren, too, who, along with her gallery in Paris, is the executor of the estate and the co-producer of Sturtevant’s video works.

In starting with the long hallway to the exhibition space that we were given, there is a puzzle right off the bat. It can be a challenge to draw people in and to make them understand that there’s an exhibition at the end. One of the very first pieces that Peter and Sturtevant placed was the dog, Finite Infinite (2010). It’s striking, like you’re literally running along with the dog down the hallway to the target at the end [Sturtevant’s Johns Target with Four Faces (study) (1986)]. The dog runs again and again into the wall; it’s endlessly repeating. It sets up the notion of the frustration of progress, related to how her whole project went against the idea of a straight, progressive narrative of art history.

Here, in Study for Muybridge Plate #97: Woman Walking (1966), she strides in front of the lens like in an Eadweard Muybridge, positioned in front of her own versions of Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol, and James Rosenquist. It’s a nod to photography, the most “copying” medium. It’s about action, the circulation of images and the frustration of circular motion like this wallpaper of an owl whose head keeps turning. It’s so weird—we’re pretty sure she just grabbed it off the internet for her 2013 Serpentine show. The exhibition is trying to speak to the consistency of her project. It’s almost shocking how she stuck to her guns pretty much from 1964 when she began recreating the works of other artists.

AM: Even with all of the criticism.

IL: Absolutely. The more you learn about her the more you realize she played an incredible long game. It took a really solid internal compass and mind to stay on this path. She had nothing if not a strong mind. Strong mind, strong opinions, strong personality. I really wish I could have met her.

AM: The way that Warhol Cow Paper (1996) is installed reminds me of the same cows in the stairwell in the education wing.

IL: Yes. And we have the Target with Four Faces by Jasper Johns upstairs. We get asked a lot if we are going to hang the originals with her works side by side. I understand the impulse but I think to her, direct comparison was less interesting than having to hold the original works and repetitions in your mind. If you put them side by side the differences would be quite extreme. But while you’re looking at it here, if you’re not fooled, you’re at least going to go along with the fact that it’s the Johns target. She hated when people would call her work a “copy” because copy implied something different. She said in interviews, I do it as closely as I can without copying it because once you copy it, it becomes something else. Two ideas she often returned to that are helpful and also infuriating are, “The object is crucial but not important,” and “Process is crucial but not important.” So yes, she had to learn how to paint like all these people, yet that was never the end objective.

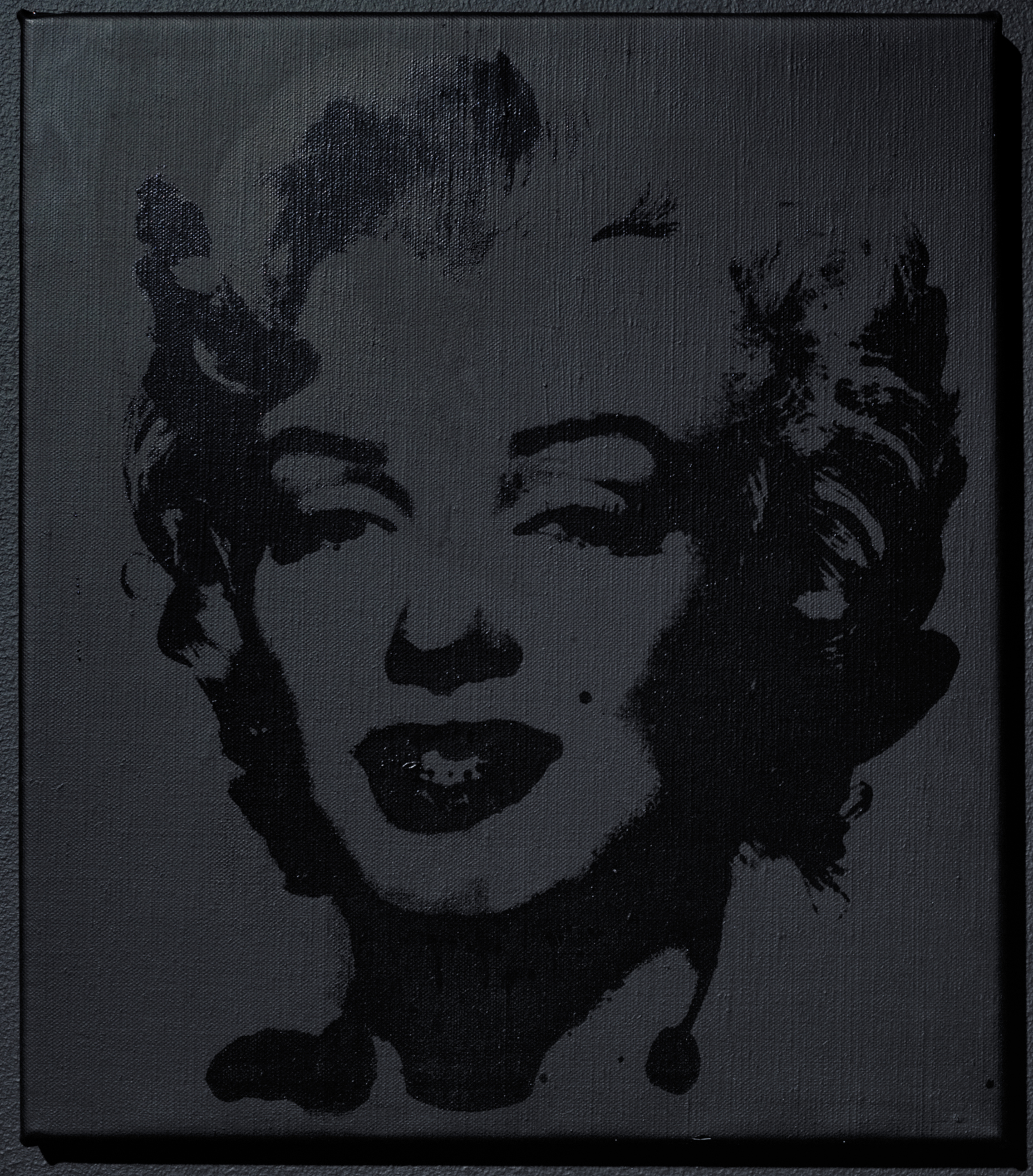

This little nook is a self-portrait gallery that’s not self-portraits, they are like stand-ins for Sturtevant. Traces of her. Here she is dressed up after the Man Ray photograph of Marcel Duchamp for the Monte Carlo Bond masqueraded in disguise. One reason why Duchamp was such an important artist to her was that she loved how he was always disguising himself. All his alter egos. And this great Warhol Marilyn, this black-on-black combination, is one Warhol never did himself.

AM: Both Warhol and Lichtenstein gave her a lot of room to do whatever she wanted with their work.

IL: It’s a gamut of responses. Artists like Warhol seem to have been supportive, or at least, not obstructing. She basically called his bluff. He said, wouldn’t it be great if everybody used silk screens so no one could tell if the artwork was by the painter or someone else, and she said okay, give me your screens! The apocryphal story is that she went to The Factory in the 1960’s and found the small flowers screen but not the Marilyn screen. So she went back to the same film still, took it to Warhol’s screen guy, and had a new screen made. It’s as though Warhol Black Marilyn (2004) was a copy of the screen itself. But there were other artists who were pretty actively hostile to her.

Duchamp Relâche (1967) is her and Robert Rauschenberg recreating Duchamp’s 1924 photograph that was originally modeled after a painting of Adam and Eve from the Renaissance. With these layers of repetition, it’s not as straightforward as it seems. This early film project, Duchamp nu descendant un escalier (1968), is after a movie from the ’50’s by Hans Richter called Dreams Money Can Buy for which Richter invited artists to make dream sequences. Duchamp’s dream sequence featured a nude descending the stairs. Sturtevant repeated it and interspersed rotary discs. Along with her fascination with Duchamp and his alter egos, Duchamp Wanted (1969) suggests Sturtevant positioning herself in the role of an outlaw and acknowledging the fact that she operated outside of the system.

This show is the only solo museum show dedicated to her work organized by a U.S. museum since the 1973 at the Everson Museum in Syracuse. It included a selection of Sturtevant’s work after Joseph Beuys, Warhol and Duchamp. This room is a nod to those key players.

AM: To clarify, is Double Trouble a retrospective? She once said, “Nobody wants a retrospective; once you’ve had a retrospective, you’re done.”

IL: She was pretty adamantly opposed to the idea of a retrospective. She also didn’t love to be in group shows because she liked to think in what she called “total structures.” Her work relies upon tensions and contexts that are greater than any one piece. A retrospective implies a chronological march through an artist’s production; her work doesn’t really work that way. Again, there’s sort of a frustration of development. We felt, too, that that wasn’t the most fruitful way to present her work. We added a few pieces and a few things moved around after she passed, but she had seen a floor plan that I would say is about ninety percent of what we have here. In the end, she really did say to Peter that this was his show. Which is a big deal for her, considering her position regarding the notion of a retrospective and her preference for total structures. She was very, very involved, as was the case with every other show that had been done. For her to relinquish control was a very big deal.

These Fresh Widows are actually versions that she had made in 2012. She had originally repeated these works in 1992 for a show. Then she did a show where she wanted more of them so she just made more. That’s where it really starts getting interesting. At that point, is she repeating herself or is she still repeating Duchamp?

AM: Was it difficult dating the works?

IL: Absolutely. Quite purposefully, the studio and the estate’s archival record-keeping has been very bad. She perpetuated misinformation, questioning what we really gain from putting so much emphasis on biography. I have a lot of sympathy for people who were working on the catalog raisonné!

Another great anecdote about her and Joseph Beuys: she claims that she started working with Beuys to counteract the criticism that she was only interested in artists who were kings of the market. In the early ’70s, he was not a big market name. After the Everson show, she did a show at a gallery here in New York of all Beuys works. That show closed in spring ’74, which was before Beuys arrived in America for his first visit. So American audiences’ first exposure to Beuys was actually through Sturtevant.

Prior to her engagement with the repetitions she was part of the whole downtown scene. She participated in happenings and was close to Rauschenberg, Johns, and Claes Oldenburg. But in ’67 she recreated Oldenburg’s store and he felt quite threatened by it. She found an empty storefront in the East Village just a couple blocks away from where Oldenburg opened his in ’61 and she made her own versions. It doesn’t look exactly the same but it’s close. When we were putting the catalog together we found Virginia Dwan’s photographs of the opening of Sturtevant’s store which had been labeled in the Dwan archives as “Oldenburg at the opening of his store.” (laughter)

Dillinger Running Series is another great work that plays with her notion of herself as an outlaw. It’s loosely based on Beuys’s Dillinger action. On his first visit in 1974 to America, Beuys found himself in front of the Biograph Theater in Chicago outside of which Dillinger, the gangster, was shot. Beuys decided to do an impromptu performance based on that. He ran out of the doors, fell down in the street as if he’d been shot, then got up and did it again. So, in Sturtevant’s version, she had herself photographed running dressed in her great Beuys-like shearling coat. These are still images that she then activated by placing them on the rotating turntable. One stipulation of the piece was that it must be in its own room, but it has exit points letting the projection, at times, escape.

In 1974 after the New York show, she reached the ultimate point of frustration with the continued misunderstanding of her project. She was worried that if she kept putting work out there to have it misinterpreted it would lose its power; so she completely withdrew for about a decade. We don’t know of any works that she produced at the time, but those could very well come to light later. Obviously during that decade some really interesting things started to happen in the art world.

AM: Appropriation Art.

IL: Exactly. In 1985 within this new context she had an amazing reemergence in group shows and a solo show at White Columns. Everyone was very eager to rewrite her as the “grandmother of appropriation.” While she was quite adamant that that was not her project, she did appreciate it as something to negatively define herself against. There is a difference in the quality of reproduction: with her there is still a craftsmanship-like nature to it.

What’s always interesting is who she chose to repeat. One of the first things you notice is that it tends to be mostly all men. There are three known exceptions. Very early on she did a few Niki de Saint Phalle pieces. They’re all destroyed now. She repeated a Yvonne Rainer dance, too. What does it mean to repeat a dance? Every time a dance is restaged it’s a repetition. In 1995 she did a Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster work. A lot of people tend to think she’s making a feminist critique. While she has a really complicated relationship with feminism, in the interview we published in the catalog between her, Bruce Hainley, and Michael Lobel, she says: no, it’s not that I’m not a feminist, it’s just that I don’t think about things in that way. Nobody says “male artists.” If you consider that her project relies on the moment of confusion through instant recognizability, well, who are the most recognizable figures in the market? That’s what she had to work with. Maybe it’s an innate feminist commentary but not one she necessarily foregrounded. It’s still amazing who she honed in on.

AM: I thought it was incredibly uncanny.

IL: Especially when she started engaging with this new generation. A lot of them are outsiders, gay males like Felix Gonzalez-Torres and Robert Gober. Also, the Gober show [Robert Gober: The Heart Is Not a Metaphor at MoMA, October 4, 2014 to January 18, 2015] was up concurrently with ours and the same wallpaper ended up being a happy coincidence.

AM: Oh, you didn’t choose that on purpose with the Gober show curators?

IL: Gober Genital Wallpaper and Gober Drain (1994/95) was always going to be in the Sturtevant show.

AM: There are so many connections to the MoMA collection and current exhibitions. Why was it decided to hold the exhibition at MoMA as opposed to MoMA PS1? Do you think that MoMA’s collection better represents the history Sturtevant interrogated and inserted herself into?

IL: It had to be here. Both Peter and Sturtevant felt really strongly that the exhibition would have a lot more power here because of that tension with the permanent collection. It needed something to push back against. There needed to be the possibility of wandering in through Sturtevant: Double Trouble’s photo gallery and thinking that you were in a collection installation. I think her work really thrives on that moment of confusion. That’s how I encountered her work. I saw it in a group show somewhere and recognized it, then I saw the label and got frustrated. That was as far as I chose to engage with her. So getting assigned to the show has really been a process for me. I love what a friend of mine said while walking through the gallery: wow, she’s really an artist who makes you meet her more than half way. I responded, yes, but if you do, you’re rewarded.

For this to be a homecoming for her, I think this is the only real place that could have that power. It’s funny, there are always tons of people taking photos in front of the Gober wallpaper and in front of the double Marilyns. My guess is that nine out of ten of them have no idea or don’t care that they’re not real Warhol’s.

AM: (laughter) Since we’re so deeply engaged with art and its history, it’s difficult for us to think that people don’t care, but it happens.

IL: Right. Here we have Pacman (2012). She started doing video in 1998 and that became the primary focus of her output for the last decade or so of her life. In this work it’s clear she’s a crazy genius. In the 2000s she started to do video works that go beyond direct repetition. She started pulling not just from the art world but from visual culture as a whole. I think it’s no accident that this is from right when the Internet and camera phones were starting to thrive. I think she was beginning to wonder if her project of repetitions was still as powerful in a place where suddenly everything could be Googled. This is Sturtevant responding to and expanding on that while still keeping her project consistent without working in a traditional fine art context.

If there was anyone who was constantly paying attention it was Sturtevant. This wall has the earliest repetition in the show and her latest work in the show. Ethelred II is an abstract 1961 painting from a series before she started making the repetitions. When you get up close you can see what it actually is: a paint tube that she sliced open. Another phrase she always returned to was “looking at the understructure of art.” It’s fascinating that as early as 1961 her project was literally cutting open the tools of art-making. It looks like a bloody mess. It was about what we value as a society and how art and aesthetic production mirrors that. I think she thought that our society was inherently violent. There is the sense of almost cautionary anxiety about what society really values and why.

AM: And that brings us to the Quentin Tarantino piece the painting is mounted on: KILL (2003/2014).

IL: Right, which she claims she got from a Kill Bill poster. She hated the movie. She found it completely gratuitously violent. She talked about Quentin Tarantino as an example of the vast, barren interior of man. Again, there’s the notion that society is a pretty violent place.

AM: And that within all this time it has not changed and perhaps become worse, more obvious.

IL: Right. Sturtevant moves from hands-on traditional work to digital work – the form changes – but the content is strikingly consistent. This is a vinyl wallpaper. The cow and the Gober wallpaper were both hand silkscreened for the exhibition. We actually worked with the same company out of Brooklyn that produces Andy Warhol’s wallpaper. We had to get special permission from The Warhol Foundation.

This is one of the works that she considered to be the crowning achievement of her video work: Elastic Tango (2010). It’s her own little greatest hits of her video works into which she randomly interspersed clips filmed from the television. Confusing repetitions with random cultural detritus. I don’t think it’s any accident that it looks like a display in a store, in a Best Buy.

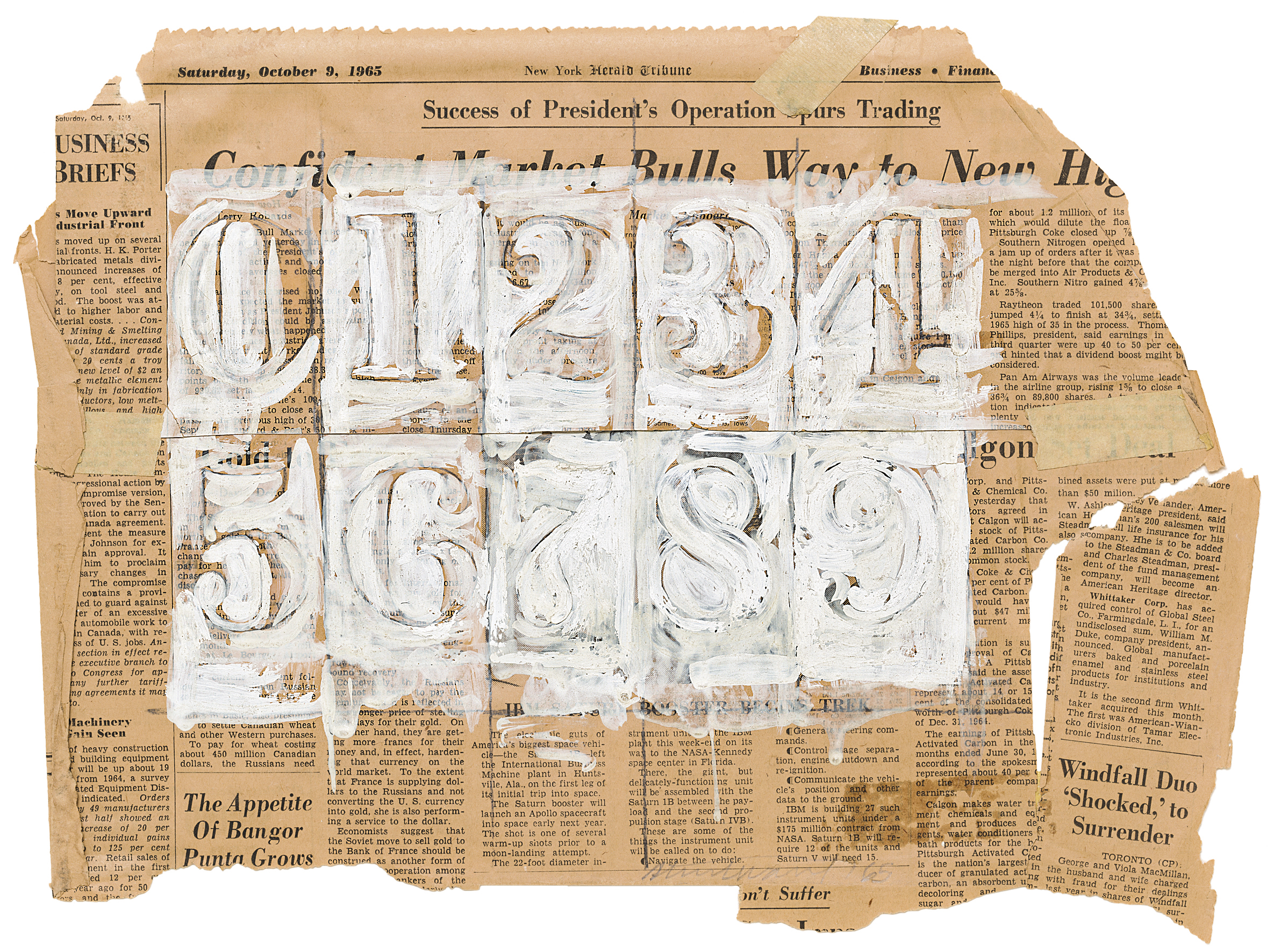

This is one of my favorite works: Johns 0 through 9 (1965). It’s so subtle but to me really drives home how she called out other artists on their own claims. The zero to nine motif was one which Jasper Johns has returned to more frequently than any other throughout much of his practice. And he worked on newsprint quite frequently. Here you have Sturtevant’s version. She conveniently left the headline of the newsprint quite visible. It’s the front page of the business or finance section of the Herald Tribune from the same week in 1965 in which her first solo show opened at the Bianchini Gallery. It’s an article about a new high in the stock market that had been precipitated by the president’s successful gallbladder operation or something and by the escalation of the war in Vietnam. Johns has always claimed that he picked these numbers because they are completely impersonal and they just are what they are. When he originally started working with them he layered them on top of one another so that they didn’t imply any sort of sequence or meaning. She’s really saying, how can you say that? Of course numbers mean something. Of course art isn’t happening in a depersonalized void. I think Peter asked Johns once how he felt about her and her work. He said, well, I think I feel how any of us felt, that she does others’ work better than she does mine.

AM: (laughter) That’s interesting since we’re right next to one of Sturtevant’s Stella paintings, which would have been incredibly painstaking to make.

IL: Right. There’s a great anecdote about a Sturtevant Stella work at LA MOCA. Somebody walked in and said: That’s the worst Stella I’ve ever seen. And then somebody replied, Yeah, but the best Sturtevant.

She made the Stella black paintings in 1989, but she somehow managed to track down the guy who had the same industrial black paint that Stella used for his years before. She went through the motions of finding the exact paint, made really detailed sketches and then made them in her studio. She went through a learning process. Whether or not it’s exact enough to fool an expert is beside the point. And it’s another case of her calling out an artist with famous dictums. Stella said in ’64, what you see is what you see. With her, you know, what happens when it’s not? (laughter)

This Warhol is another great example where she made a version of this Warhol Diptych (1973/2004) in 1973 and wanted to include it in a show at the 2004 MMK Frankfurt am Main retrospective. When the owner wouldn’t lend it she just made another one. So this is the 2004 version of her 1973 work. For her it was never really a problem.

AM: Who would you say is the audience for her work? Do you need to have a certain level of recognition or background?

IL: She was pretty clear on that. To her mind, as long as you knew she was repeating something then she thought it wasn’t necessary for you to know the original. I think it is harder to engage with if you don’t have that grounding in art history but I think enough of these works are in the collective cultural memory to know that they’re not by somebody named Sturtevant. Even that name is confusing. It destabilizes you.

Returning to how important it was to have the show here at MoMA, Peter was immediately interested in engaging with or disrupting the permanent collection. We worked with the Painting and Sculpture Department to find a way to insert her into the permanent collection. Visitors have responded in varied ways. I think a lot of people are very surprised to encounter it. This video work (points to The Dark Threat of Absence Fragmented and Sliced [2003]) is really crazy. Whereas most of her video works moved away from direct repetition, this references a Paul McCarthy work, The Painter, in which McCarthy is dressed up in a blond wig as a grotesque Willem de Kooning. We also have some of Sturtevant’s rotary discs here masquerading as Duchamp’s next to the original Fresh Widow (1920) and the Monte Carlo Bond (No. 12) (1924) in the corner for those who want to make the connection.

AM: I overheard a conversation the first time I was here between two young guys arguing about whether or not Duchamp’s readymade was Sturtevant’s work.

IL: Oh, funny. That’s great, that’s so great.

AM: What has the critical reaction been like?

IL: I only really hear the responses of the people that I’ve taken through. But even with colleagues at the museum, before we did the exhibition, seventy-five percent of people would say: I have no idea whose work that is. And that’s pretty rare for the staff.

AM: Has there been a general critical acceptance of the show?

IL: I would say that the press has been very favorable. People really responded to the context of her being at MoMA. There have been outliers to who have completely missed the point and have been appalled that MoMA would turn over a gallery to forgeries. But in a way that’s so perfectly off it almost proves the point. Now that we’ve gone through the appropriation cycle and Postmodernism, there are so many more entry points to her work. It’s no longer all that strange.

AM: We touched upon the complicated process of historicizing her. She engaged with almost every “movement” of her generation yet refused to be classified in any way. Is there anything further you would like to add about what you took away from working on the show?

IL: I think for me it was the realization that from the very beginning she seemed to have such an eerily clear idea of where she was going. Her foresight was really uncanny, which I think makes placing her both really easy and really hard. She perfectly circumscribes the moment she’s working in but then also completely surpasses it. At the end of the day, my biggest lesson from the show is that this exhibition asks way more questions than it answers. (laughter) Struggling with how to place her is a good thing. And maybe it can’t be resolved.

Be First to Comment