Bruce Nauman: Disappearing Acts opened in March at the Schaulager Museum in Basel, Switzerland, to rave critical reviews and social media buzz. Here in New… Continue Reading Master Manipulator: Bruce Nauman at MoMA

Posts tagged as “moma”

In a gallery off to one side in the ongoing (through May 28, 2018) retrospective on the photography of Stephen Shore at the Museum of… Continue Reading Art World Meets Instagram

On a curtain of vinyl strips are projected two reproductions of Henri Matisse’s painting La Danse. Even in their dematerialized, doubled state the dancers are instantly recognizable, but after several seconds they vanish, replaced now by a Warhol portrait of Mao that is paired with a Mondrian Composition. The sequence continues, a parade of Van Goghs, Cézannes, Kandinskys, and Klees all flashing across the curtain seemingly at random, as if they accompanied an absent art history lecture that disregarded all pretense of chronological or stylistic organization.

This work by Lea Lublin, Dedans le musée/Pénétration d’Images (1971), invites the viewer to behold these familiar works and then pass through the curtain, at once metaphorically entering their pictorial spaces and enacting their physical rupture. Appropriately, it enjoys pride of place at The Museum of Modern Art’s compelling, dizzying Transmissions: Art in Eastern Europe and Latin America, 1960–1980, dominating a small gallery at the heart of a show that foregrounds a widespread ambivalence towards prevailing artistic trends shared by artists on both sides of the Atlantic, who sought not only to engage with such trends but ultimately reshape them.

Photography: Sean Nesselrode

A collaborative effort by curators Stuart Comer, Roxana Marcoci, and Christian Rattemeyer, the show is drawn almost entirely from the museum’s permanent collection, with nearly half of the three hundred works on display for the first time at MoMA. The majority of these are recent acquisitions that have come to the museum thanks to the efforts of C-MAP (Contemporary and Modern Art Perspectives), an in-house initiative dedicated to pushing beyond the warhorses on view in Lublin’s installation to focus on comparatively understudied work from Asia, Eastern Europe, and Latin America. Transmissions is the first major curatorial intervention to result from C-MAP and the latest in a recent line of MoMA exhibitions that, in welcoming new figures into a pantheon of twentieth- and twenty-first century art history, have found the museum playing a long overdue but much welcome game of catch-up. Latin America has recently been spotlighted in retrospectives of Lygia Clark, Horacio Coppola, and Grete Stern, with Joaquín Torres-García next in line; Central and Eastern Europe have been represented by Isa Genzken, Sigmar Polke, and Alina Szapocznikow.

In early February, Curatorial Assistant Ingrid Langston and IFA MA Candidate Ashley McNelis toured the MoMA galleries. Langston assisted MoMA PS1 Curator Peter Eleey in organizing the exhibition Sturtevant: Double Trouble at MoMA, which runs from November 9, 2014 to February 22, 2015. Double Trouble is timely not just in light of the artist’s recent passing, but also because it is only Sturtevant’s second American-organized solo show since the 1970s. The intervening four decades—in which Sturtevant was largely ignored by the art world—have afforded her audience the time and hindsight to catch up with her intelligently penetrating vision. Sturtevant: Double Trouble also juxtaposes traditional art historical narratives (represented by works in MoMA’s permanent collection) against works from Sturtevant’s reactionary oeuvre. The exhibition will be on view in the third floor Special Exhibitions Gallery and the fifth floor Sue and Edgar Wachenheim III Painting and Sculpture Gallery at MoMA until it heads to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles from March 21 to July 27, 2015.

Ashley McNelis: I understand that Sturtevant actively combated the use of curatorial strategies at other institutions. What was working with her at MoMA like?

Ingrid Langston: Unfortunately, I never got to meet her personally. She was working with Peter Eleey closely and was planning to come out for the installation before she passed away in May 2014. Peter went to Paris every few months to meet with her, but by the time I came on the project she was not really traveling much. So I never worked with her directly, which is a shame, but probably also made my life a lot easier. We did work closely with her daughter, Loren, too, who, along with her gallery in Paris, is the executor of the estate and the co-producer of Sturtevant’s video works.

In starting with the long hallway to the exhibition space that we were given, there is a puzzle right off the bat. It can be a challenge to draw people in and to make them understand that there’s an exhibition at the end. One of the very first pieces that Peter and Sturtevant placed was the dog, Finite Infinite (2010). It’s striking, like you’re literally running along with the dog down the hallway to the target at the end [Sturtevant’s Johns Target with Four Faces (study) (1986)]. The dog runs again and again into the wall; it’s endlessly repeating. It sets up the notion of the frustration of progress, related to how her whole project went against the idea of a straight, progressive narrative of art history.

Here, in Study for Muybridge Plate #97: Woman Walking (1966), she strides in front of the lens like in an Eadweard Muybridge, positioned in front of her own versions of Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol, and James Rosenquist. It’s a nod to photography, the most “copying” medium. It’s about action, the circulation of images and the frustration of circular motion like this wallpaper of an owl whose head keeps turning. It’s so weird—we’re pretty sure she just grabbed it off the internet for her 2013 Serpentine show. The exhibition is trying to speak to the consistency of her project. It’s almost shocking how she stuck to her guns pretty much from 1964 when she began recreating the works of other artists.

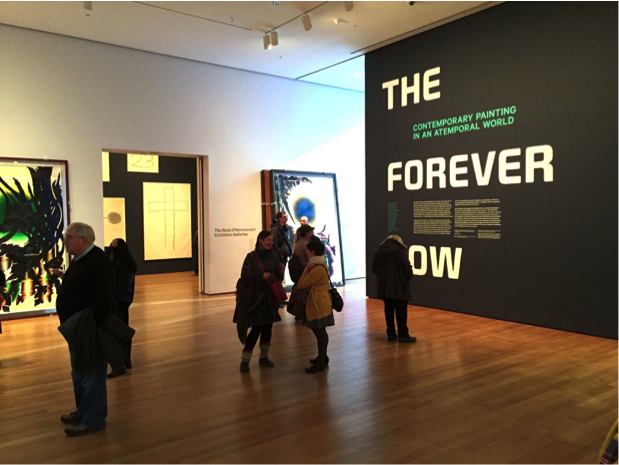

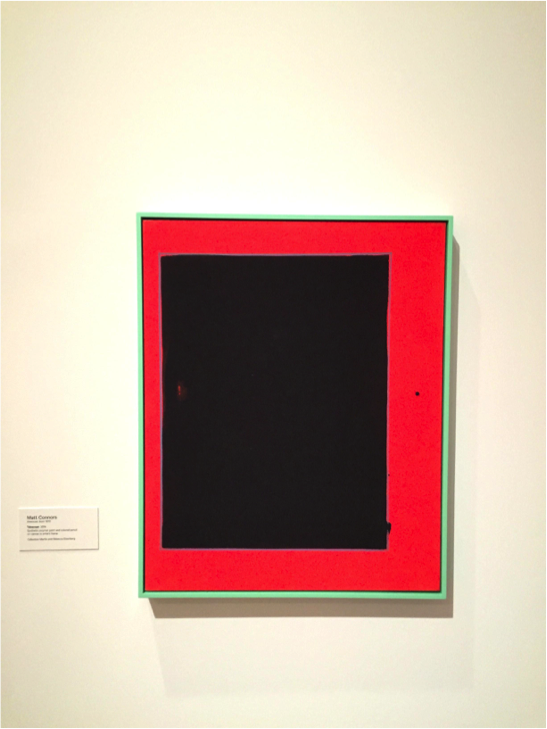

Proclaiming the current cultural moment as one in which all historical eras coexist, The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World (on view December 14, 2014 to April 5, 2015) constitutes the Museum of Modern Art’s first survey of contemporary painting in over thirty years. Occupying half of the museum’s uppermost floor, The Forever Now presents works by seventeen international living artists that is grounded in art historical references but shuns the constraints of art historical chronology. While vibrant and engaging, an exhibition of such stature merits criticism concerning the market-driven nature of much modern-day painting. The show asserts a-temporality as its theoretical basis, appearing first and foremost as MoMA’s unwavering and bold (though risky) attempt to take seriously—and defend—painting when its integrity is severely undermined by the whopping demands of the ever-expanding contemporary art market.

The Forever Now presents painting in the wake of the proliferated image and Internet culture, drawing its thesis from the definition of “a-temporality” (or timelessness) first proposed by science fiction writer William Gibson. In the words of curator Laura Hoptman, the artists represented in the show relieve their art of “modernism’s burden of progress.”[1] The exhibition features predominantly abstract works in diverse media. Striving to present a multitude of inspirations and styles in an a-temporal world, the curators (Hoptman with curatorial assistant Margaret Ewing) provide the viewer an opportunity to experience timeless art in full scale. There are, among other works, Joe Bradley’s crude drawings on canvas, Julie Mehretu’s grey scribble paintings, Oscar Murillo’s colorful patchworks, and Mary Weatherford’s striking neon works. All of them are large, vibrant, and audacious, as if openly making the declaration: painting is alive and well.

Marina Abramović is back in New York City, but this time, she won’t be seen. On her last visit, Abramović performed The Artist is Present (2010) for the blockbuster MoMA retrospective of the same name. For 736 hours and 30 minutes, Abramović sat immobile in MoMA’s atrium faced, one by one, by silent visitors. Most recently, she spent 512 hours at the Serpentine Gallery, guiding visitors through an empty space and occasionally presenting them with an everyday object.

Now, at Sean Kelly Gallery, Abramović’s Generator—a participatory work that focuses on “nothingness” and sensory deprivation—is on view (through December 6, 2014). Facilitators place blindfolds and noise-cancelling headphones on participants before leading them into the main gallery. Once inside, participants can move however they want (though told it is a “slow-moving” piece), touch whatever they want, and stay as long as they want. When ready to leave, the blindfolded raise their hands and a facilitator guides them out. Every movement is documented and presented on Tumblr; this aspect of the piece, however, only becomes apprehensible once outside the space, in front of a computer screen. During the exhibition’s run, Abramović will partake, too—unannounced and daily—but, of course, participants will not be aware of her presence.

As is fitting with his perfectionist manner, American photographer Christopher Williams took an active collaborative role in the design and installation of his career-spanning survey, Christopher Williams: The Production Line of Happiness (on view July 27 to November 2, 2014), at the Museum of Modern Art. First mounted at the Art Institute of Chicago, the exhibition currently resides at MoMA and travels next to the Whitechapel Gallery in London.

Visitors may be puzzled upon arriving in the entrance area outside the exhibition’s galleries. Instead of the typical introductory wall text and related visual references, the entrance walls are covered with liner notes from a recording and installation views from past exhibits. Similar to the recent Alibis: Sigmar Polke 1963-2010 retrospective at MoMA, wall labels have been replaced with a handout. This unconventional use of wall space and lack of information in the galleries are typical of Williams’s shows.

Through this installation at MoMA, Williams challenges the viewer by aiming to avoid a “neutralization” of his work within different spaces. Indeed, he has a history of using non-traditional display practices to create a consciousness of the institutional presentation of art. The artist began to develop his unique approach to display when studying at CalArts under Conceptualists Michael Asher, John Baldessari, and Douglas Huebler. Williams’s professors were renowned for creating architectural interventions and disruptions in museum and gallery shows as a way to complicate conventions of presentation.

Ken Johnson’s controversial review of Now Dig This! Art and Black Los Angeles 1960-1980, currently on view at MoMA PS1 through March 11, has become nothing less than an art world scandal, sparking a deluge of denouncements from readers, an open-letter and petition against the New York Times backed by prominent artists, critics and art historians, and even an attempted rebuttal on the art critic’s Facebook page, with continued debate in the comments section. Some of Johnson’s most problematic assertions focus on questions of originality and “quality,” each clearly sited in the historical standards of high Modernism. “Black artists did not invent assemblage,” he protests. “In its modern form it was developed by white artists like Picasso, Kurt Schwitters, Marcel Duchamp, David Smith and Robert Rauschenberg.” Later, the critic attacks the use of socially-engaged themes during a period in which art was supposed to be purged of realism and representation: “The art of black solidarity gets less traction because the postmodern art world is, at least ostensibly, allergic to overt assertions of any kind of solidarity.”[1]

These accusations would be relevant if Johnson’s concerns were shared by the exhibition’s curator, Columbia Professor Kellie Jones, but Now Dig This! is not intended to de-throne Duchamp and Rauschenberg. Jones presents Now Dig This! as an art historical survey of the African-American cultural scene in 1960s-1980s Los Angeles; she frames the exhibition as an arrangement of episodes rather than a singular narrative. Each gallery focuses on a different theme, style, or institutional network, thus allowing the viewer multiple points of entry into a wide body of artistic and historical material. Johnson’s attachment to the master narrative of Modernism is the first (and perhaps most innocuous) interpretive error of his review, revealing the degree to which this evolutionary historical model remains deeply ingrained in our thinking.

The following is an abridged transcript of a conversation between IFA alumna Roxana Marcoci, Curator of Photography at The Museum of Modern Art, and the author, which took place at MoMA on 7 August 2012.

Four IFA Master’s students respond to the opening for Diego Rivera: Murals for The Museum of Modern Art.

Photograph by Rafael Doniz. Image via The Museum of Modern Art.