The works in Mousetrap constitute Natalie Terenzini’s drive to paint the female form in an authentic and subversive manner. Her subject, an anonymous, caricature-like figure, repeats throughout the body of work as she engages in private yet everyday activities. With bold colors and striking, solid shapes, Terenzini depicts this woman as she goes about her day-to-day activities such as reading, smoking, searching the fridge, and speaking on the phone. Occasionally, she is joined by other nameless and similar figures; an undetermined cast of characters in partial narratives. The most striking scenes are those where this central character engages in grooming activities and forcibly presents the viewer with intimate, often nude and revealing vignettes. The viewer watches as she combs and styles her hair after a shower, plucks body hair from her breast before a mirror, or sits on the floor of her bedroom, legs spread, waiting for a mousetrap to snap.

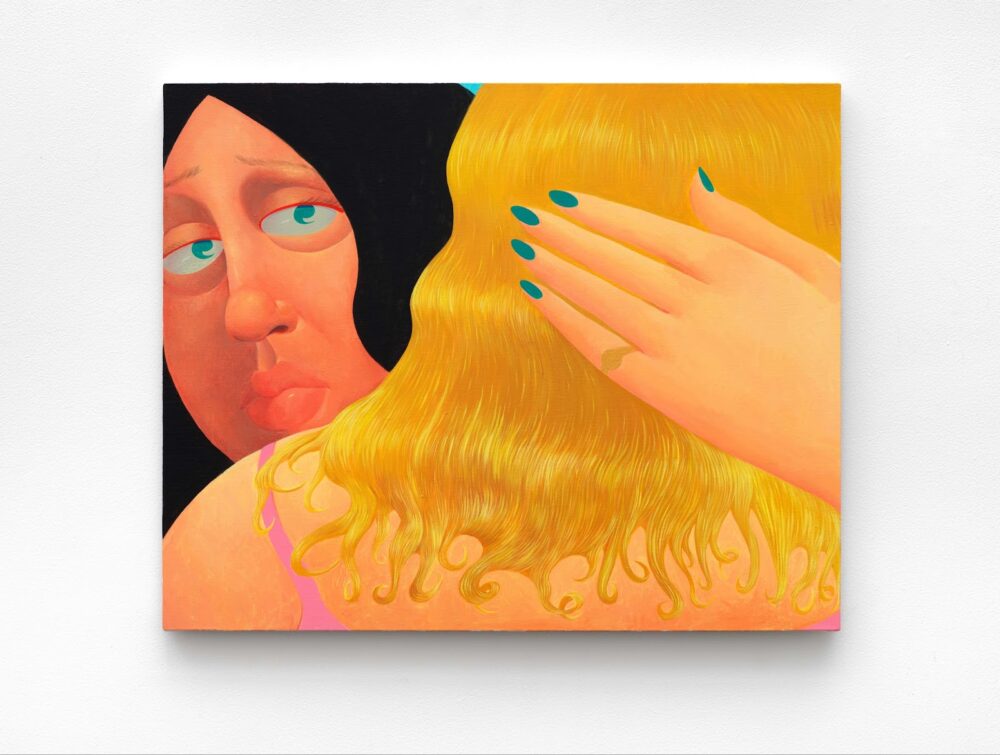

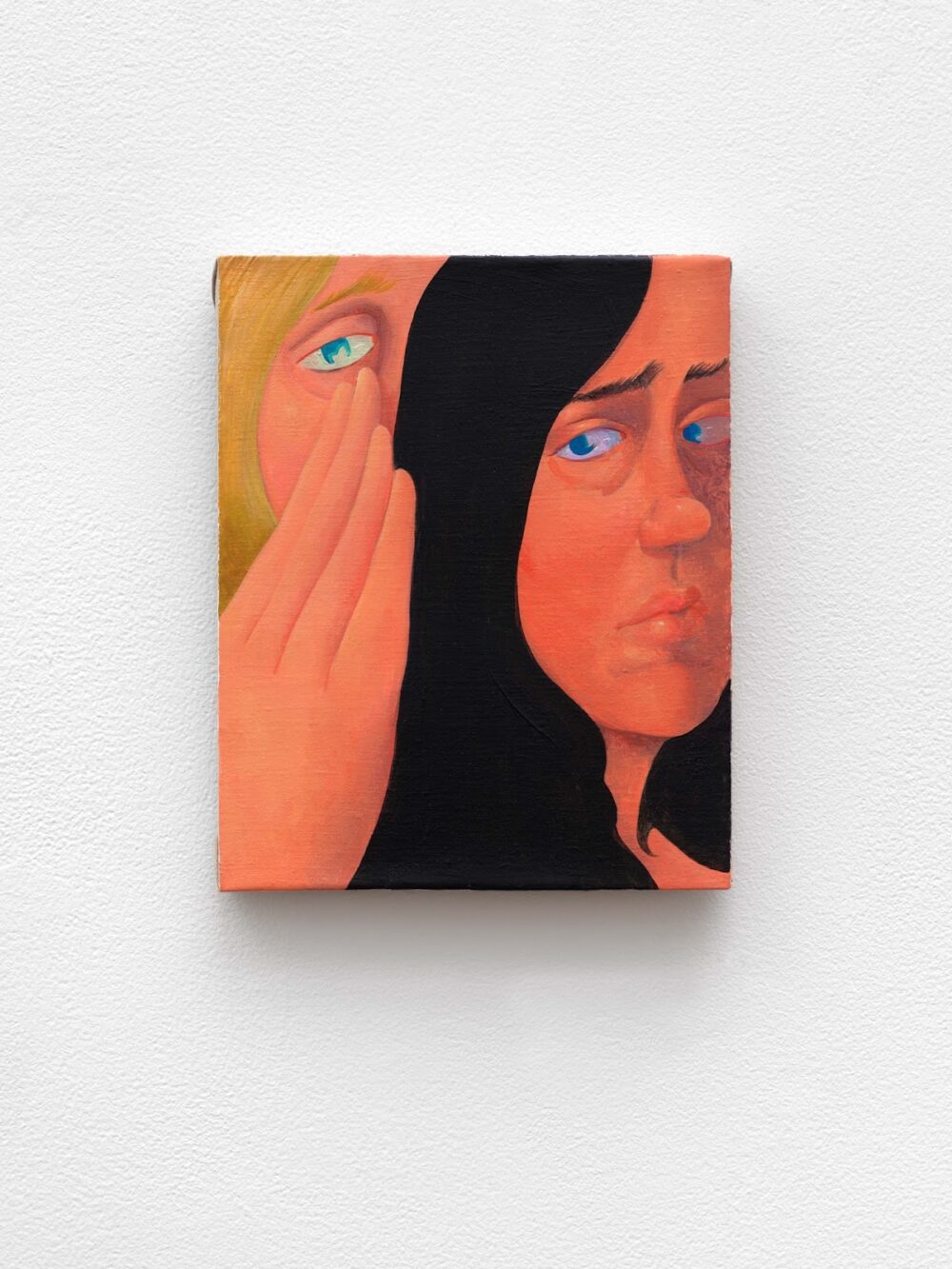

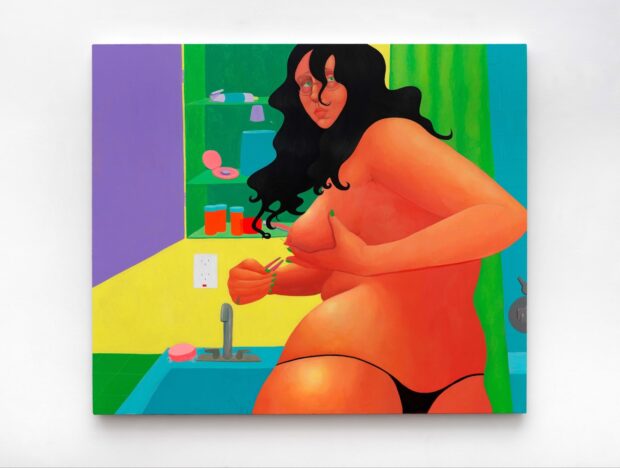

In Mousetrap, Terenzini never over-determines her subject. Her figures are devoid of intricate bodily details, rendered in fleshy oranges and pinks with mops of high-contrast dark hair. Dressed or undressed, her subjects appear opaque and thus commanding, contained by sharply defined edges. Terenzini’s main character becomes increasingly dominant throughout the body of work in each composition’s foreground, at times consuming most of the picture plane. She places her figures in non-specific spaces rendered through mostly flat shapes in planar background arrangements. Her simplified forms and implied spaces furnish the subject as a certain “everywoman,” or even an “everyperson” figure—a site for projection. She is no one in particular, and so she is anyone and everyone; she is anonymous. And yet, this avatar and her suggested environments are close enough to recognizable realities that they serve to imbue the works with a distinct sense of narrative.

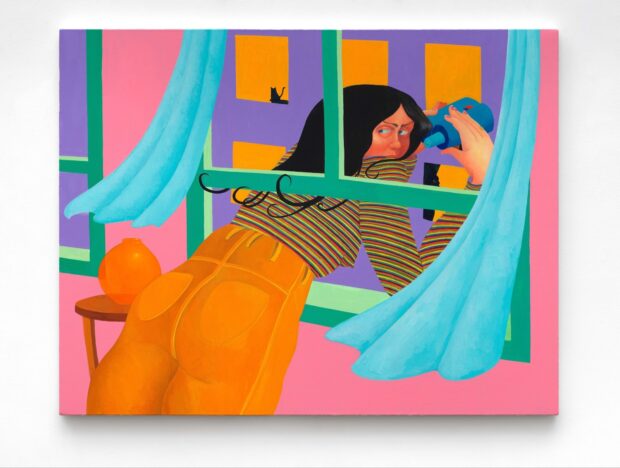

When viewing the exhibition in its entirety, it becomes quickly apparent that the subjects in Mousetrap are all one and the same. Terenzini renders the same figure throughout the works with dark hair, strong brows, and a consistent embodiment. And yet, the artist succeeds in stopping just short of specificity. She achieves this anonymity through the aforementioned lack of intricate detail and generalized, domestic environments, but also through compositional choices—a partially or fully obscured face (see the book in What Do You Know or the telephone/hair in I Hope I Hear From You), a close-up or cropped view of a scene (I Hope I Hear From You), or a total lack of environmental context (Secret or I’ll Be Seeing You). Where the viewer might start to reach for more information in order to identify this repeating figure, Terenzini withholds. As for the compositions where Terenzini renders a more complete subject, the vague familiarity of the narratives intervene and, aided by their immersive size, assert self-projection over identification.

Terenzini’s colors are fantastical: candy-colored pink, neon blue, green, and purple, lemon yellow, and a distinct fluorescent orange pop from the canvas and draw the viewer into their whimsical settings. These colors repeat throughout the exhibition and link each pictured moment in time to the others. Luscious and over-stimulating, outlandish yet used to depict mundane existence, the palette acts in service of Terenzini’s project of cartoonish simplification. In this way, Terenzini utilizes color to increase the sense of mirrored reality throughout the works—one that is only referred to and not truly present. At times, the colors in Mousetrap are so immediate that they momentarily overpower the content of the work, holding the viewer in a visual honeytrap.

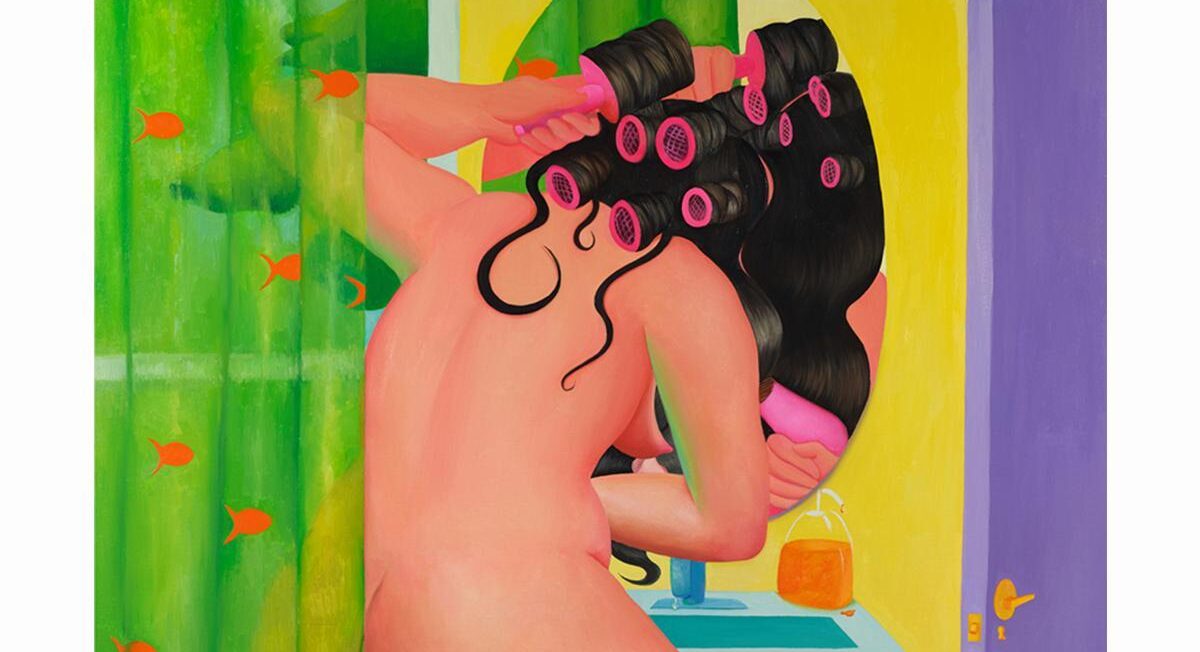

In Making an Appearance, the subject in the center of the composition immediately draws the eye, while colors on all sides compete for attention. The edge of the lime green shower curtain and the purple of the open bathroom door balance the weight of the composition while creating tension through complementary hues; these two verticals frame the nude subject’s body as she readies herself to “make an appearance.” Her body perches oddly on the edge of a blue tub, her left hip seemingly hovering over what would be the concave portion of the structure. Yet here she sits, as if her position has been rendered as an afterthought—like she is not really placed in the space, not truly there. Both the woman and the retreating cat in the right hand corner are incomplete and visible only from behind. Neither truly “make an appearance.” In fact, both subjects actively strive to not appear; the woman’s head blocks the reflection of her face in the mirror as the cat exits the room. Who is it, then, that makes an appearance? Perhaps it is the cockroach at bottom left, whose presence seems incongruous in a room from which a cat has just fled. Perhaps it is the viewer, who walks into the bathroom unacknowledged by its occupant.

In the arresting (and perhaps the strongest) composition Mousetrap, color and metaphor run rampant. Orange and green constitute foreground and background and hold the subject as she sits with legs spread on a bedroom floor, smoking and looking at pornography. Mousetraps abound, beginning with a literal mousetrap at the bottom left (notice a mouse escaping under the bed—a similar relationship to cat-and-cockroach in Making an Appearance). Then come the figurative mousetraps: the porn, the cigarettes in the ashtray and on the nightstand, the beer can, and most overtly, the open vagina, which mirrors the shape of the mousetrap. Terenzini leaves the viewer to draw their own conclusions—are we to equate the vagina with the other vices scattered throughout the composition? How do we reconcile anonymity—plainly referenced via the subject’s obscured face—with the intimacy of the splayed legs?

In certain paintings, Terenzini’s subject maintains a forbidding awareness of her audience, often asserted through the woman’s outward, skeptical gaze, as in Look Out, Medicine Cabinet, and What Do You Know. Through this acknowledgment of ongoing voyeurism, Terenzini imbues the paintings with an unsettling quality. In doing so, she subverts the art historical mechanism of the male gaze. The subject in Mousetrap is the one who exercises the gaze, challenging the viewer’s intrusion, even suggesting a violation. Artist and subject alike beg the question – what kind of interaction does the presence of intimacy without trust or consent elicit?

At first vibrant, exciting, and aesthetically inviting, Terezini’s compositions become increasingly disruptive as they permeate the subconscious. The artist presents a parallel reality—one that asks the viewer to both project their own experiences and identities onto the work and to evaluate the ethical considerations of their intrusion into the spaces present. In the gallery setting, the works invite the viewer to knowingly enter this interaction—to buy in, literally and figuratively. With their alluring palettes and on-trend, slightly abstract figurative bend, there is no doubt Terenzini’s less provocative works will sell. But the eponymous piece, Mousetrap, and the other few like it?

With a plethora of references to vaginas, pornography, cigarettes, pill bottles, late-night binging, and other vices, It remains to be seen if buyers have the stomach for the works in Mousetrap that directly reference the more insidious trappings and exploitative strategies of a capitalist art market itself. Either way, Terenzini’s project succeeds.

Mousetrap is Brooklyn-based painter Natalie Terenzini’s first solo exhibition and runs from April 7th through May 27th at Thierry Goldberg Gallery on the Lower East Side.

Be First to Comment