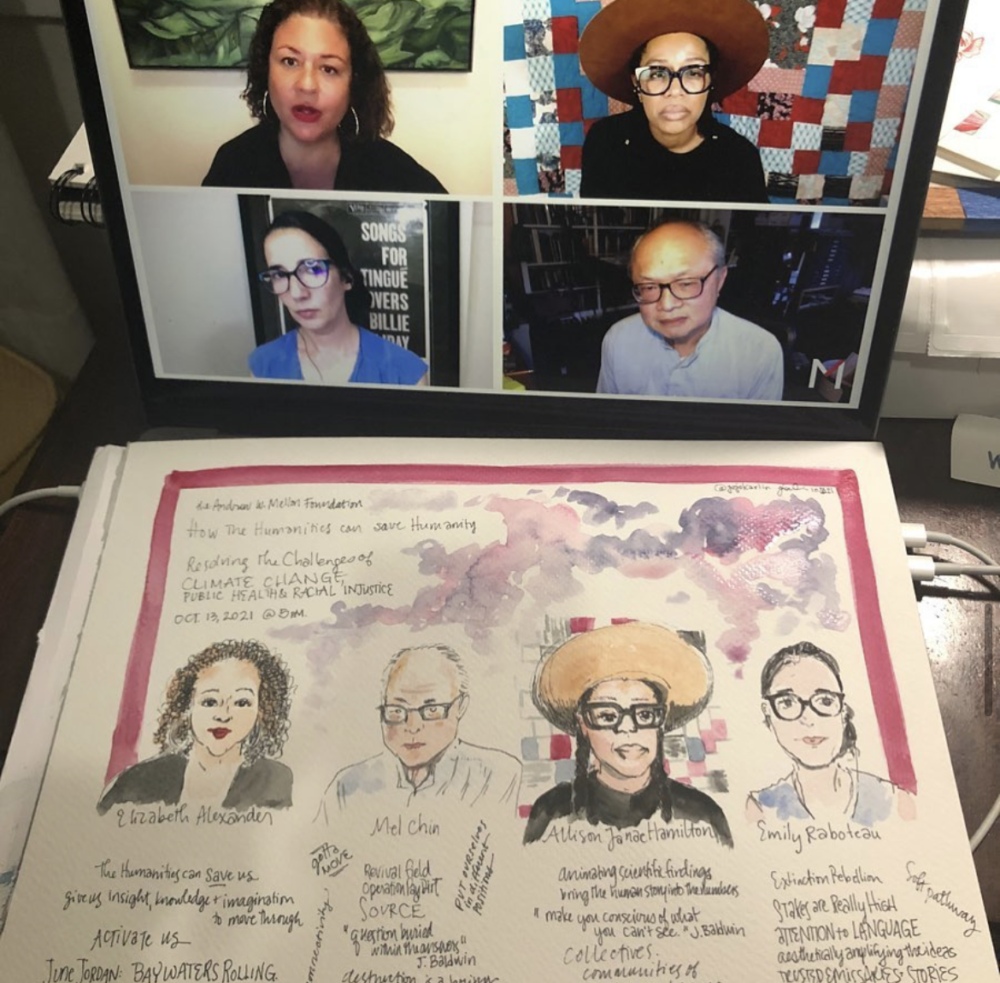

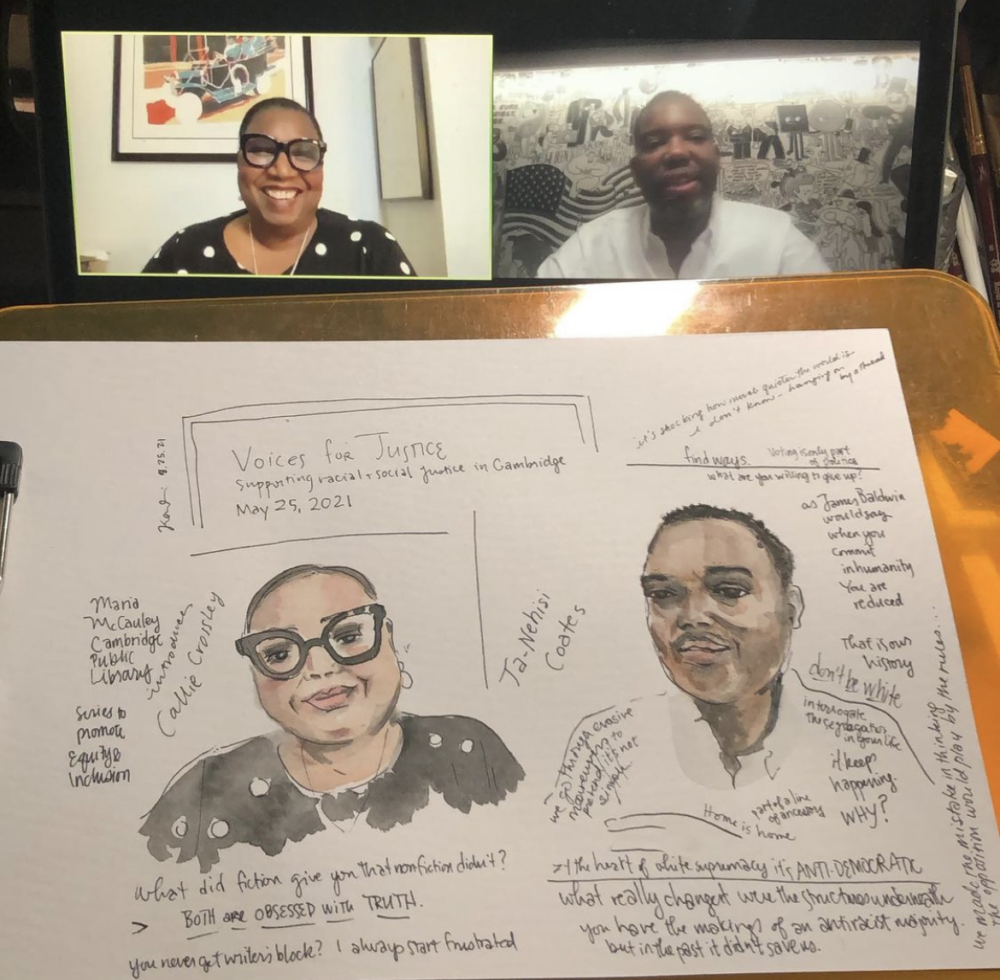

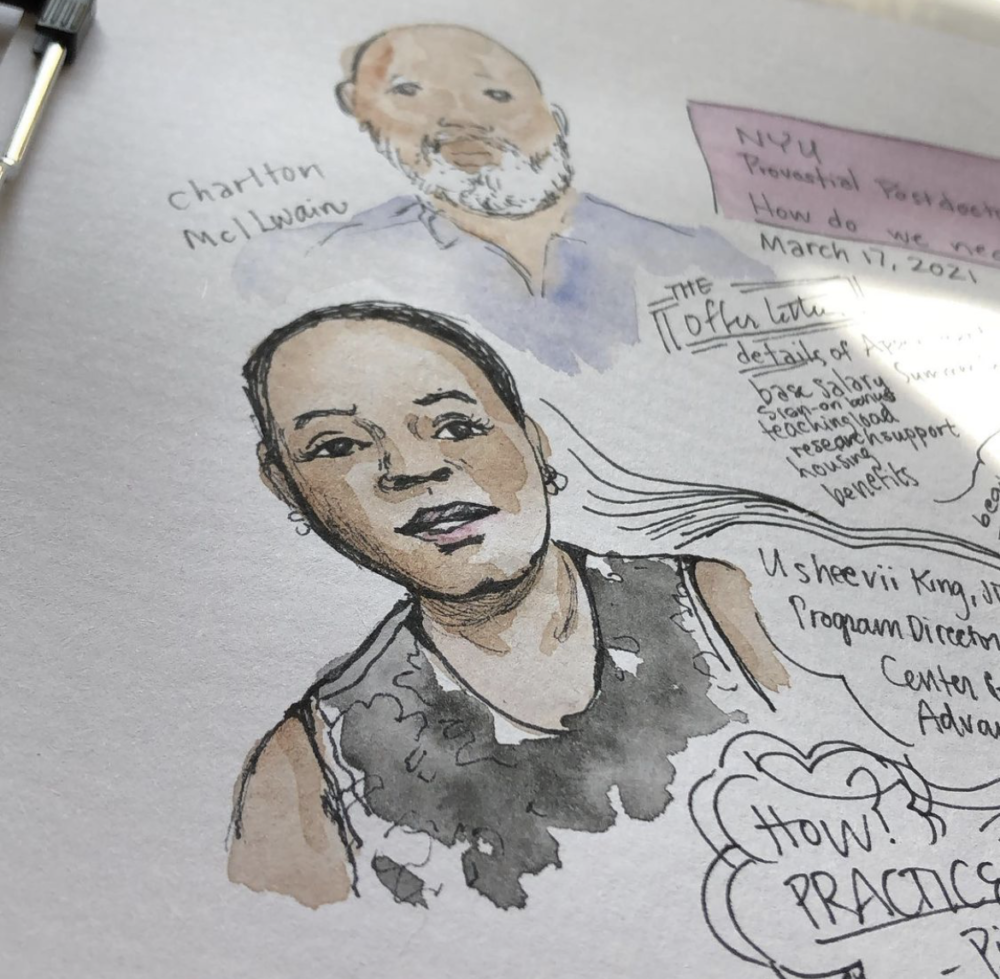

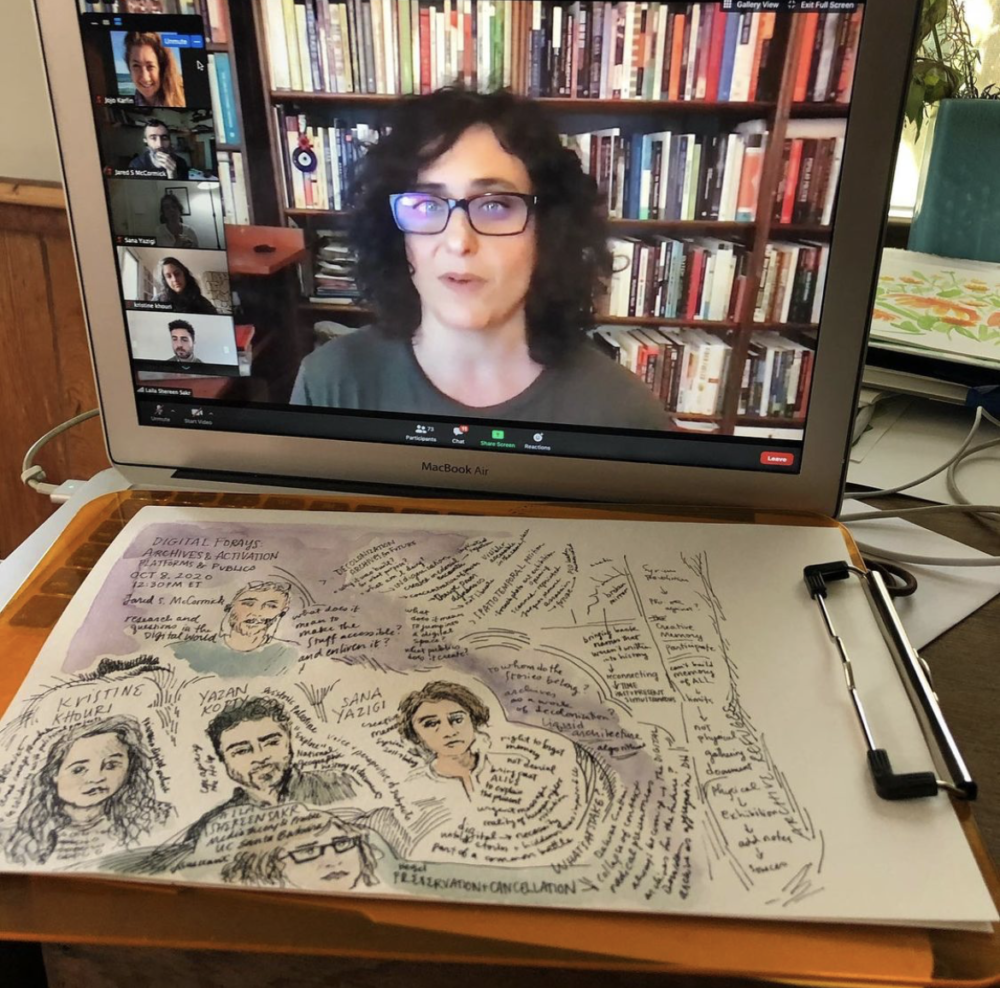

As the end of 2021 approaches, the world faces a moment of reflection following nearly 24 months of public health obstacles, calls for social justice, and reckoning with a new way of living with the use of virtual platforms. The arts had to adjust to online programs, performances, exhibitions, and educational outreach. Despite the need for social distancing, digital innovations enabled people to connect, collaborate, and create in new ways. Dr. Jojo Karlin is a graphic scholar who found artistic refuge in the virtual space of Zoom meetings, drawing and painting Zoom participants in meetings, lectures, and conferences. Karlin is a provostial postdoctoral fellow at NYU, having received her doctorate in English Language and Literature/Letters at the CUNY Graduate Center in 2020.

I met Dr. Karlin through one of my seminar courses at the Institute of Fine Arts, in a class that aims to publish a collection of texts from NYU’s Special Collections using Manifold (a virtual platform for disseminating scholarly research). With her affinity for the arts, from doodling as a child to theatrical performance, Karlin integrated her use of illustration into her research as a means of re-articulating and processing information. For instance, she embarked on a series of illustrations for her dissertation Yours Sincerely, Virginia Woolf: Virginia Woolf’s Poetics of Letter Writing (2020). Karlin has extended her process of “multimodal” note-taking from her personal academic writing to the realm of social media, where artists have been able to share their creative projects. In this interview, I sought to find out how Karlin’s artistic practice not only plays with the virtual world’s immediacy and interpersonal interaction but also how she speaks to the ever-changing global reality with which the fine arts must contend.

NB: Tell me about your relationship with the visual and performing arts and your current position in the digital humanities.

JK: Making things was always pretty natural… My father plays the violin and was always very musical, so art was always a part of my understanding of how you approach the world and think about the world. What are the humans in this room feeling together, how can they express it themselves and take ownership over the things that they are getting out of the moment. When I went to graduate school, it was partly that question of how this approach works in literature for me and in a new digital space where the ways we interact with literature is so different. So I was interested in these digital spaces and the influence they have on the ways that we read and share literary experience. The question of letters brought me in many ways to questions of autobiography and memoir. I was taking seminars with Nancy Miller who wound up being my dissertation director and she let me draw my responses to things. And as soon as I was allowed to draw responses to things, I was like, “Oh, well this actually makes a lot of sense in terms of my interest in communications and how it works within language and materials, and how we translate that in different spaces.”

NB: Regarding your series on images of people in Zoom meetings, how has being an actor in the past helped you capture specific characteristics of your sitters?

JK: I’ve always been interested in theater in the ways you connect in a room with other people. Audience engagement [is an important aspect of that]— how do you bring people into a room and provide a feeling of being connected at that moment? And so that question of human connection was always there. The move to Zoom illustration offered [me the chance] to feel as though I am with these people, because so much of my experience in a seminar or a conference has to do with the staged experience of being in a room with an audience and the performer. And in that academic space, you have people presenting in a specific way, but Zoom flattens that because you are all in your grid and because you have this stimulus of your personal environment. It also puts all these various people on the same page. In understanding three dimensions on a two-dimensional interface, I like to draw from movement so I can have a sense of a person’s volume. Drawing people from speaking in real-time allows me to have a sense of that volume even though it is distorted by the screen and camera angle, and it is a different experience from drawing from a photograph. But I like to understand the gestural expressions of a person speaking.

NB: Do your sitters know you are drawing them?

JK: My first drawings were in live conferences where they used a sticker system, so if someone did not want their picture taken they had a sticker. I went up to people after the conference and asked how they would feel about me posting a drawing of them on social media. And they all said, “go ahead and post it!” So it was very interesting in terms of whether or not people know. Now people who go to meetings with me know that I am likely drawing them and they don’t seem to mind, especially on Zoom.

NB: There are often notes beside your images, would you consider these textual elements indispensable to your artwork?

JK: The notes I take are what is informing my drawing of the person because I am drawing people moving in their little Zoom windows. I find it to be a very interesting way of talking to people about their scholarship, for me it’s an ice-breaker, showing my engagement in their work with the notes I take. But also, my concentration on portraits and faces considers the question “how do you decide what you’re focusing on and what [is it that] leads you to [these ideas and accepting them]?”

NB: Finally, the definition of art has vastly expanded in the wake of social media. Do you think your technique is a genre of art that dismantles the elitist hierarchy of art fundamental to fine arts institutions?

JK: The question of what makes an artist has been broad for many years, as well as the question of what any particular art is for, to be hung in a museum or just meant to be a personal notecard, begs the question of how we define great art. I’m a museum-goer and I sell some art, but I feel so outside of art because I just haven’t been trained formally. I took some classes here and there, but it took me a long time to claim that identity as an artist. Two major themes that play a part in this are questions of expertise and the writable web. Ever since the web became a place with the possibility for anyone to publish themselves online, you have a different sense of how we evaluate expertise. Then you consider institutions’ relationship with their social media presence while their scholars cling to a traditional power of authority. So it becomes a question of who has that authority to say “this is of merit, and this is not,” and if you can have people doing the same thing of equal merit in different places and make a living off of it— does it really matter which one is better?

Karlin’s artwork condenses intellectual dialogue and simulated human interaction into personal responses that touch audiences, subjects, and the artist herself with new modes of thinking and communication. Seeing the interaction between the humanities and digital spaces allows us to consider the future of not only human collaboration but also the trajectory of how we define and utilize art. Will you embark on a creative journey in your next Zoom meeting?

Please find more of Dr. Jojo Karlin’s work on Instagram (@jojokarlin) and on her website jojokarlin.com. Noelle Y. Barr is a master’s student at NYU’s Institute of Fine Arts.

Related Media

- Collins, Kathleen. “Jojo Karlin on drawing ideas,” from Indoor Voices podcast, episode 57 (Apr. 2021). https://indoorvoicespodcast.com/2021/04/12/episode-57-jojo-karlin-on-drawing-ideas/.

- Jojo Karlin. “About,” website. Accessed November 13, 2021. http://www.jojokarlin.com/about/.

- NYU Libraries Communications. “Libraries Fellow Visualizes Concepts Through Graphic Scholarship,” blog post (Nov. 2020). https://guides.nyu.edu/blog/Libraries-Fellow-Visualizes-Concepts-Through-Graphic-Scholarship.

Be First to Comment