Factories always fascinate me, as I often wonder how the things I eat, use, or consume are manufactured by workers or machines: transforming raw materials… Continue Reading “Whose Utopia” – Cao Fei at the Museum of Modern Art

Posts published in “Alumni Updates”

On April 27, 2015, IFA PhD candidate Anne Wheeler and IFA MA alumna Sarah Zabrodski sat down to discuss the Solomon R. Guggenheim’s current exhibition, On Kawara—Silence. Wheeler is the assistant curator of the exhibition. Zabrodski blogs at emergingartcritic.com.

Sarah Zabrodski: On Kawara proposed most of the exhibition sections and was a close collaborator in the early stages of exhibition planning. What was it like working with the artist?

Anne Wheeler: Senior curator Jeffrey Weiss met On Kawara in 2005, in the process of acquiring the painting Title (1965) for the National Gallery of Art, so he had a relationship with Kawara before approaching him in October 2011 about doing the Guggenheim show. I came onto the project full time in April 2012, and worked for about a year before meeting Kawara himself. We first met almost two years ago to this day, on April 28, 2013—a day I remember clearly—a Sunday. Kawara sent Jeffrey and me a map of a park, with a dot drawn in the location where we were to meet him. We went, and we waited, and finally he came walking toward us, and brought us to a picnic table where we sat and talked with him and other members of his family until the sun went down.

Kawara was very deliberately not a public figure—he was infamous for his refusal to grant interviews, show up for openings, or make public appearances. He told us early on: “I am an artist that never made any public statements,” and we always tried to be extremely respectful and protective of this choice, and of his privacy. Jeffrey took Kawara on a walk-through of the museum early in the process, and we brought him models of the Guggenheim and maquettes of his Date Paintings and other work to help him conceptualize the exhibition within the space without actually having to be there. We always measured what was worth bringing to him, what was worth asking.

Our meetings involved a lot of exhibition planning and talk about the facts of each series—how and when certain artworks were made, or what they were made for—but ultimately the meetings turned out to be more conversational than strictly business. We would go in with questions about, say, where to place a certain Date Painting, but we would end up discussing cave paintings, gravity, the role of art throughout time, the history of human consciousness—really big topics, and his opinions were quite profound. After each meeting, I’d leave thinking, “What was that?”—and then as a researcher, to always have these new “assignments” was such an education for me.

As far as the artwork, though, we never talked about why—“why” questions were not discussed. It’s been one of the funny and difficult things about giving tours, responding to the why questions: “Why these newspapers? Why the red, blue, and gray? Why this or that?” I can say all of the things that I think about the work, but I can never reference anything he actually said.

In early February, Curatorial Assistant Ingrid Langston and IFA MA Candidate Ashley McNelis toured the MoMA galleries. Langston assisted MoMA PS1 Curator Peter Eleey in organizing the exhibition Sturtevant: Double Trouble at MoMA, which runs from November 9, 2014 to February 22, 2015. Double Trouble is timely not just in light of the artist’s recent passing, but also because it is only Sturtevant’s second American-organized solo show since the 1970s. The intervening four decades—in which Sturtevant was largely ignored by the art world—have afforded her audience the time and hindsight to catch up with her intelligently penetrating vision. Sturtevant: Double Trouble also juxtaposes traditional art historical narratives (represented by works in MoMA’s permanent collection) against works from Sturtevant’s reactionary oeuvre. The exhibition will be on view in the third floor Special Exhibitions Gallery and the fifth floor Sue and Edgar Wachenheim III Painting and Sculpture Gallery at MoMA until it heads to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles from March 21 to July 27, 2015.

Ashley McNelis: I understand that Sturtevant actively combated the use of curatorial strategies at other institutions. What was working with her at MoMA like?

Ingrid Langston: Unfortunately, I never got to meet her personally. She was working with Peter Eleey closely and was planning to come out for the installation before she passed away in May 2014. Peter went to Paris every few months to meet with her, but by the time I came on the project she was not really traveling much. So I never worked with her directly, which is a shame, but probably also made my life a lot easier. We did work closely with her daughter, Loren, too, who, along with her gallery in Paris, is the executor of the estate and the co-producer of Sturtevant’s video works.

In starting with the long hallway to the exhibition space that we were given, there is a puzzle right off the bat. It can be a challenge to draw people in and to make them understand that there’s an exhibition at the end. One of the very first pieces that Peter and Sturtevant placed was the dog, Finite Infinite (2010). It’s striking, like you’re literally running along with the dog down the hallway to the target at the end [Sturtevant’s Johns Target with Four Faces (study) (1986)]. The dog runs again and again into the wall; it’s endlessly repeating. It sets up the notion of the frustration of progress, related to how her whole project went against the idea of a straight, progressive narrative of art history.

Here, in Study for Muybridge Plate #97: Woman Walking (1966), she strides in front of the lens like in an Eadweard Muybridge, positioned in front of her own versions of Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol, and James Rosenquist. It’s a nod to photography, the most “copying” medium. It’s about action, the circulation of images and the frustration of circular motion like this wallpaper of an owl whose head keeps turning. It’s so weird—we’re pretty sure she just grabbed it off the internet for her 2013 Serpentine show. The exhibition is trying to speak to the consistency of her project. It’s almost shocking how she stuck to her guns pretty much from 1964 when she began recreating the works of other artists.

On December 16, 2014, Marci Kwon sat down with Alexis Lowry Murray and Delia Solomons, who co-curated the exhibition Sari Dienes at the Drawing Center. All are PhD candidates at the IFA.

MK: To begin, how did you come up with the idea for the show? And what was it like putting it together?

ALM: It was surprisingly simple. While researching Jasper Johns, I came across Sari as a side note in the catalogue for the Jasper Johns retrospective, organized by Kirk Varnedoe. Delia and I had been talking about curating a show together, and think I waited only twenty minutes before I talked to her about it. We looked up the Sari Dienes Foundation website, and were immediately interested in the rubbings she made, and the indexicality of that process. We made an appointment to go to the Foundation – we simply called their phone number – and when we got there it was instantly clear to both of us that an exhibition was the best idea. We had gone up to the Foundation open-endedly–for a moment I even thought about doing a dissertation on Sari–but we immediately knew an exhibition was best.

DS: The works looked incredible in person–really delicate and yet with this substantial scale. While examining them in the barn, we instantly pictured them on white walls in a gallery or museum space in New York, back in the urban context where she originally made these works.

MK: You first saw them in a barn?

ALM: Sari’s work is housed in a barn that is cared for by her Foundation. Barbara, the curator of the Foundation, and her husband Rip live in upstate New York where Sari used to live. Sari used to work in the Foundation’s barn, and it is literally chock-full of art.

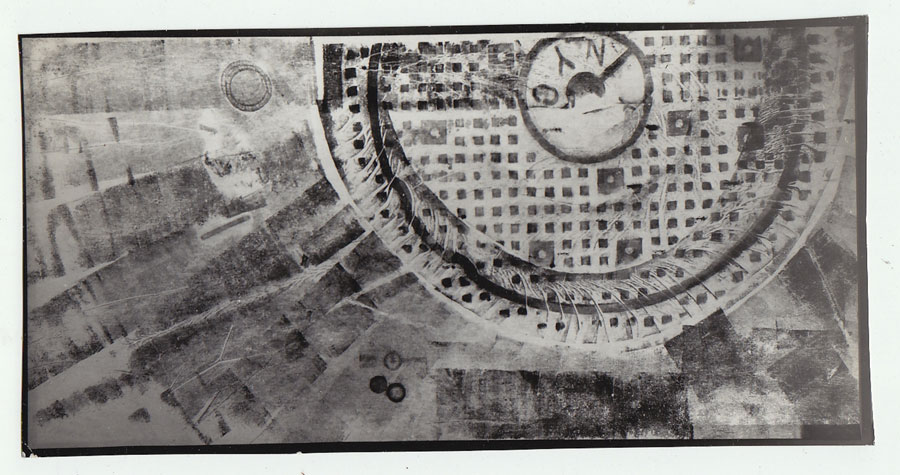

The exhibition of Sari Dienes’s work at The Drawing Center (on view October 8 to November 16, 2014) highlighted the artist’s innovative and experimental approaches to mark making in her large-scale rubbings of New York City streets from the 1950s. On November 13, the curators of the exhibition (and current PhD candidates at the IFA), Alexis Lowry Murray and Delia Solomons, led a public tour that introduced Dienes’s work by examining the dynamic interplays of processes and textures in her drawings. During the tour, Solomons and Lowry Murray gave context to Dienes’s practice by underscoring her creative exchanges with contemporaries such as Jasper Johns and John Cage. Following the tour, artists Alison Knowles and Gillian Jagger talked with NYU’s Julia Robinson about their mutual interests in using found forms and textures from natural and urban landscapes in their work.

Sari Dienes (1898—1992) was born in Hungary and was a student of Purists Fernand Léger and Amédée Ozenfant. By 1936, she was Assistant Director of Ozenfant Academy of Fine Arts in London. She moved to New York City in 1939 where she soon befriended artists both established (Mark Rothko) and emerging (Johns and Cage, as well as Ray Johnson, Robert Rauschenberg, and others), many of whose names are listed in pages from the guest book from her studio. On Thursday night, Lowry Murray and Solomons emphasized Dienes’s willingness to experiment with found materials and new processes, and her subversive recoding of established notions of the authorial gesture, qualities that are as important today as they were to Dienes and her contemporaries as seen, for example, in the work of Ray Johnson, Rachel Whiteread, and Rirkrit Tiravanija.

The Leiden University Medical Center (LUMC) is a world-renowned university and teaching hospital. What few people may realize is that it boasts an art collection and free public gallery, which hosts five shows per year. The LUMC holds an exhibition of nominees and winners of the Hermine van Bers visual arts prize—a yearly award that stimulates the development of young artists—and invites contemporary artists to create site-specific pieces in a large open hall with an abundance of natural light. The collection, primarily photographs, prints, and drawings, which began 25 years ago, continues today through the efforts of one curator, Sandrine van Noort. Interestingly, the purpose of the collection is markedly different from that of institutions devoted to art. Instead, the works provide the background for photos of newborn babies, offer a temporary escape from nail-biting stress, and splash color onto otherwise depressingly industrial cement walls. The art distracts from the hospital environment and brings a labyrinthine institution down to a more human scale.

The following is an abridged transcript of a conversation between IFA alumna Roxana Marcoci, Curator of Photography at The Museum of Modern Art, and the author, which took place at MoMA on 7 August 2012.

A number of IFA students and professors will be presenting at the upcoming 2012 CAA conference in Los Angeles, February 22 to 25 at the… Continue Reading IFA at CAA: Stay Tuned

Estrellita B. Brodsky is experiencing what for many art historians is a dream come true: less than three years after receiving her PhD from the Institute of Fine Arts, she has succeeded in curating an exhibition based on her dissertation research on Latin American artists working in post-war Paris. Now on view at the Grey Art Gallery on NYU’s downtown campus through March 31, 2012, her exhibition, Soto: Paris and Beyond 1950-1970, focuses on the early Paris years of the Venezuelan maestro, Jesús Rafael Soto, a key member of the post-war international avant-garde who is today best recognized for his optically-challenging, immersive, and kinetic art. Just a week after the show’s opening, Brodsky kindly agreed to meet with me at the Grey to discuss her research, curatorial experience, and of course, Soto.

Our conversation began in the center of the Grey’s main gallery, surrounded by examples of each of the various phases explored by Soto between 1950, the year of his initial departure to Paris, and 1970, a culminating moment in his career following his first Paris retrospective at the Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris and the realization of his famous Penetrables.[1] With a Cézannesque-Cubist rendering of a Venezuelan landscape behind us and an optically challenging Plexiglas piece to our right, I asked Brodsky to start at the beginning: why did she choose to study the work of Latin American artists in post-war Paris?

Explaining that her interest in Venezuelan art is rooted in her personal history (her father arrived in the country in the 1920s, and Brodsky was a first-hand witness to the country’s booming arts scene in the 1960s), she also admitted to a certain selfishness in picking her topic.