Sailing high during Miami’s 2021 Art Week was Betye Saar’s 2019 Gliding into Midnight assemblage, making its home at the Institute of Contemporary Art. Positioned in the gallery against a backdrop of a silk astrological map entitled Celestial Universe (1998), black ceramic hands engulfed by coal reach toward the sky as a cobalt canoe hovers above a diagram of the Brookes, a British slave ship that shuttled between Africa and the Caribbean. An engraving of the Brookes diagram was first published in 1788 by the Plymouth chapter of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, depicting how people were densely packed into the ship. Here, the viewer is faced with a deeply emotional work that explores the horrors and inhumanity of the Middle Passage.

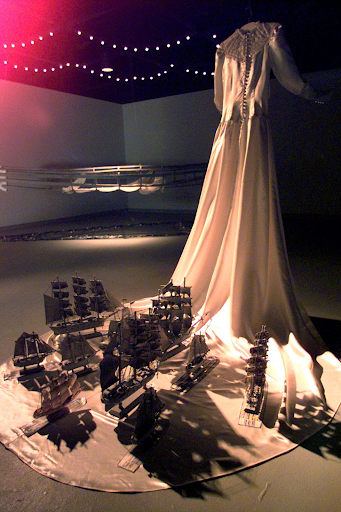

Saar has returned to the image of the Brookes in numerous works throughout her career. In Brides of Bondage, a bridal dress floats, ghostlike, and miniature sailboats chase its trail, each set atop a Brookes diagram. First shown as part of Saar’s 1998 solo exhibition, A Woman’s Boat: Voyages, at Saddleback College Art Gallery in Mission Viejo, California, Brides of Bondage evokes ancestral memories and the fate of women. For half a century, Saar has been one of the country’s most inventive and influential makers of intimately-scaled assemblage. She has brought a distinctive range of content to the medium by encompassing global culture, popular mysticism, personal history and racism in America (which she coolly refers to as “national racism”) in work that she refers to as ritualistic.

Gliding into Midnight is both stunning and horrifying, and may take its place as this generation’s J. M. W. Turner’s Slave Ship. Lauded as one of Turner’s most celebrated works, this tumultuous image was created following the highly publicized events of the Zong Massacre for display at a meeting of the British Anti-Slavery Society in 1840. While the massacre led to a trial, it was not for the murder of 133 slaves bound for Jamaica, but for the insurer’s refusal to pay the insurance claims on their lives. The judge favored the late Captain Collingwood by asserting that this case contained no claim for human people being thrown overboard as “blacks are goods and property… the case is the same as if wood had been thrown overboard” [1]. Turner grapples with this idea in Slave Ship as both the slaves and the ship wreckage intertwine in the unforgiving seas. Betye Saar has combined goods such as coal, overwhelming the outreaching black hands, in an emotionally charged call for help.

Saar, like Turner, has expertly captured the horror of the Slave Ship and the terrifying grandeur of nature through color and light that merge sea and sky. Both artists weaponize the color blue as a symbol of the ocean, which claimed the lives of a countless number of slaves who rest at its bottom. In a time so similarly tumultuous, Saar acknowledges that the abuses of empire and lack of justice for the same demographic—men of African descent—are still prevalent today. By providing us all with the much-needed reminder that the violence of bygone eras is not so far behind us, perhaps we enter a shift in the artistic cannon that is more than a movement or a moment, but an irreparably changed discourse.

Footnotes:

[1] Trevor Burnard, “A New Look at the Zong Case of 1783,” XVII-XVIII. Revue de La Société d’études Anglo-Américaines Des XVIIe et XVIIIe Siècles, no. 76 (December 31, 2019), https://doi.org/10.4000/1718.1808.

Be First to Comment