On December 16, 2014, Marci Kwon sat down with Alexis Lowry Murray and Delia Solomons, who co-curated the exhibition Sari Dienes at the Drawing Center. All are PhD candidates at the IFA.

MK: To begin, how did you come up with the idea for the show? And what was it like putting it together?

ALM: It was surprisingly simple. While researching Jasper Johns, I came across Sari as a side note in the catalogue for the Jasper Johns retrospective, organized by Kirk Varnedoe. Delia and I had been talking about curating a show together, and think I waited only twenty minutes before I talked to her about it. We looked up the Sari Dienes Foundation website, and were immediately interested in the rubbings she made, and the indexicality of that process. We made an appointment to go to the Foundation – we simply called their phone number – and when we got there it was instantly clear to both of us that an exhibition was the best idea. We had gone up to the Foundation open-endedly–for a moment I even thought about doing a dissertation on Sari–but we immediately knew an exhibition was best.

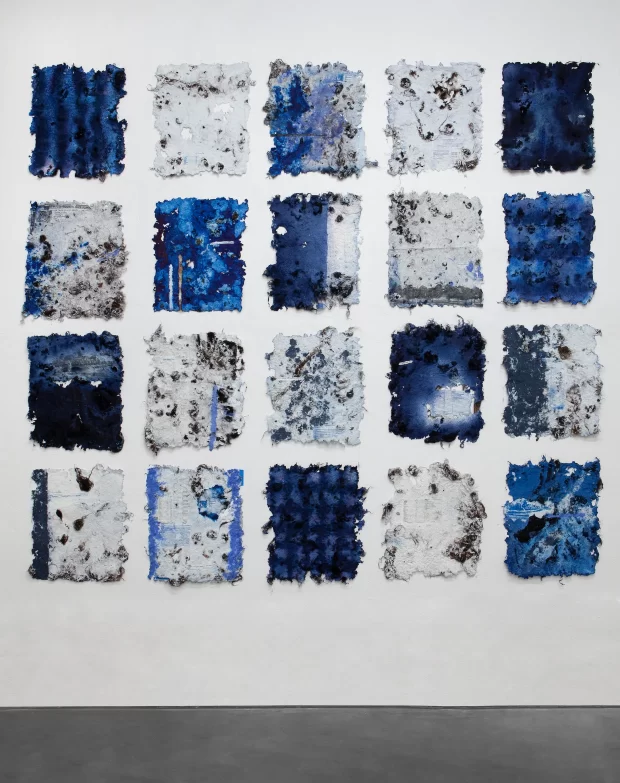

DS: The works looked incredible in person–really delicate and yet with this substantial scale. While examining them in the barn, we instantly pictured them on white walls in a gallery or museum space in New York, back in the urban context where she originally made these works.

MK: You first saw them in a barn?

ALM: Sari’s work is housed in a barn that is cared for by her Foundation. Barbara, the curator of the Foundation, and her husband Rip live in upstate New York where Sari used to live. Sari used to work in the Foundation’s barn, and it is literally chock-full of art.

MK: How did you zero in on the rubbings?

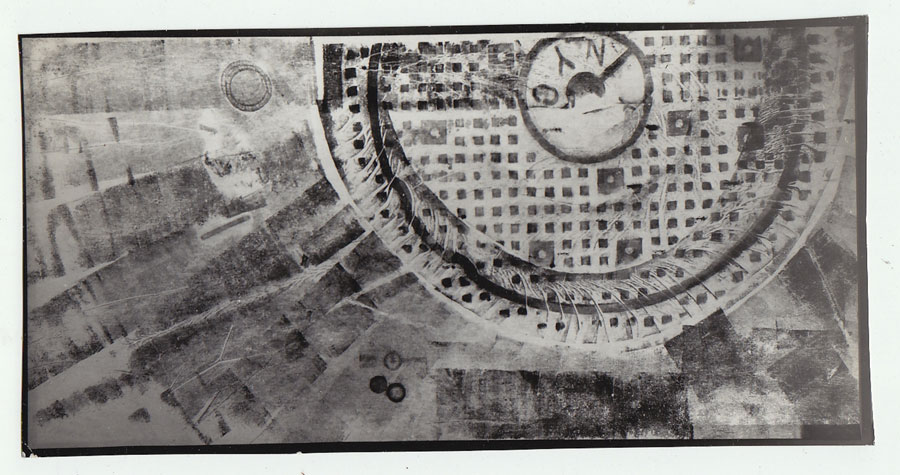

DS: We had seen a few reproductions on the website, and we were initially drawn to this moment, to the idea that in 1953 Jasper Johns moves to New York, and before he starts the Flag and Target series, the first thing he does is work with her; he holds her paper down while she makes rubbings on the streets. So, this was really rich from an art historical standpoint. We all know Johns is a critically important, canonical figure; but we became interested in Dienes as someone who was potentially pivotal and yet left out of most art historical narratives. We were drawn to the potential of that concept, and then saw the power of her works in person. On the one hand they are really accessible (they speak to a moment on the street), but we were also drawn to the fact that they speak to a turning point in art history. They combine rigor and accessibility.

ALM: They are legible in that you can sort of understand what the process is just by looking at them, but their legibility doesn’t diminish their complexity and sophistication.

MK: It seems like you guys worked really well together!

DS: We did! The best testament to that is that we have a whole list of future projects we want to work on together. But I feel like we never answered your initial question regarding why we selected the rubbings. To clarify, we looked at a lot of work. While we knew we wanted to focus on the 1950s from the start, that included assemblages, early gestural AbEx-looking work, and ceramics, not to mention her 1960s-70s Xerox work, performances, and her time with the A.I.R. Gallery, and her earlier 1930s-40s surrealist work. But from the start we knew we wanted to reintroduce this figure to art history, and to do so by offering an intelligible, recognizable image–an idea, like the urban transfer drawings of city streets and manhole covers–to call to mind when they think of Sari Dienes. That kind of editing is important on a pedagogical level.

MK: So it sounds like you guys had some idea of what you wanted, but when you saw these rubbings it was kind of love at first sight.

ALM: Yes!

MK: How did you guys decide to go with The Drawing Center with the exhibition?

ALM: Delia and I came up with a wish list of institutions that we wanted to show at. We decided to start at the top – why not? The Drawing Center was at the top of that list because of their programmatic emphasis on experimental mark-making. I had some connection with them because ages ago I interviewed for a job I didn’t get. I interviewed with the director, Brett Littman, so they had some abstract idea of who I was. They agreed to talk to us, and we came in with a proposal for a slightly enlarged show, which included a packet with images and a potential installation plan.

MK: So you were prepared.

ALM: We were over-prepared, and it was a good thing. They were interested and asked us to come back with a specific proposal for the space they had available. We came back with that, and they green-lit it. It was basically cold-calling.

DS: It can be a very mysterious process, shopping around an exhibition as independent curators. To demystify the process a bit: we prepared a two-page précis detailing the exhibition content and ideas (the timeliness and importance of the show), one page about us as curators, one page about the artist in general, five to six pages of images with labels, and a mock-up of the exhibition.

ALM: We also had ideas for public programming.

DS: Right.

MK: How long did this all take?

DS: We first visited the Foundation in the summer of 2012, so it took about two years in total.

ALM: Delia and I worked on it for seven or eight months before going to The Drawing Center. Not continually, but we went to the Foundation, created a proposal, and then went back to the Foundation. It was a little less than a year and a half between contacting The Drawing Center and finally executing the show.

MK: How did you find this kind of curatorial work relates to your academic work?

DS: I’ve always been very interested in contributing to both academia and curatorial work. I had taught before, but I had never curated an exhibition. It was a joy to be able to go through the process as an independent curator, but also to work with someone else. The IFA is known for its object-based methodology, an approach that perhaps more easily bridges academia and curating. I think the perceived divide between academic and curatorial work is often quite exaggerated; they’re very related.

ALM: Also, taking classes at the Conservation Center was crucial. The work is so precious and fragile, so some familiarity with basic conservation issues, debates, etc. was a tremendous asset. It was an exhilarating learning experience for us, especially because we were not producing an extensive publication. The only way to really tell the story was with the works themselves, to organize them in a way that would show how the artist originally installed the works in a variety of ways, with concern for tactility, and to tell the stories of her engagement with AbEx, her break with it, the influence on Johns purely through visual means. We talked endlessly about what would go beside what, because we wanted to create a syntax between the works. I’m not sure we were totally prepared for it, but it was a different kind of challenge that, for me, was ultimately rewarding.

DS: Yes, and while I definitely think we over-exaggerate the difference between curatorial work and academia, as a student, sometimes you feel that only a few people will hear a seminar paper, and only one professor will read it. With the exhibition you get to see people posting about Sari Dienes on Instagram and engaging with the art, and wanting to discuss it with us. It’s really been a positive experience.

ALM: Just letting the work be in the world.

MK: I think that should be everyone’s goal. What are you most proud of with this exhibition?

DS: I have so many favorite things, but I think that to show these important works, which have a powerful scale and yet a delicacy and strong tactility. We were so thrilled to be able to show them without glass frames– to hang the scrolls from wire, the unframed works with rare earth magnets, and to keep the original frames from 1955 (to treat those as objects)…

ALM: Ahhh Delia I was going to say the same thing!

DS: It was just so beautiful to see the work without glass. There’s something really immediate about it.

ALM: Yes, and just being able to include ephemera that is so juicy, and to be able to provide more context to the show was fun. Watching people in the space, I think they were really attracted to the ephemera. The ephemera is part of the syntax; it helped us narrate the story of this very specific moment.

DS: Exactly. The photographs of her process help us understand her work, and then to realize that these photos were published in Life just drives home the point that she was a really crucial person at this moment. The sign-in sheets at her studio also tell part of her story–on two pages alone you find the signatures of John Cage, Robert Rauschenberg, Ray Johnson, Cy Twombly, Carolee Schneemann, and Jasper Johns–her studio was a salon for some of the most experimental artists and thinkers of the time.

MK: What about audience? Do you have an ideal audience in mind for the exhibition?

ALM: Sari has been marginalized from the canon for fifty-plus years, and it was important to both of us to give her a voice again. Not just for her, but from a gender standpoint. Many women like Sari ended up marginalized from the canon, and giving them their moment is important. And the best way to do that is to tell their story. Hers is a clear story, and a true story, a story that interests a wide audience. To that end, we wanted art historians young and old, people interested in the arts, and people from her circle to feel excitement about her having a moment.

DS: Take for example the idea of orientation in her work. This is something very obvious to any audience member – she is literally taking something from the street into the gallery, reorienting it from a horizontal plane to a vertical one. Everyday pedestrian life has been reoriented – what does that gesture mean? Everyone gets it, but for art historians the idea of reorientation also relates to [Leo] Steinberg, or, as we mentioned in our gallery talk, she actually hung her work in a number of different orientations, so it also relates to [El] Lissitzky. It works on both levels, and I think Dienes’s work is pretty brilliant in that way.

ALM: I agree.

MK: Me too.

Sari Dienes was on view at The Drawing Center from October 8 through November 16, 2014.

Be First to Comment