There is a scene in the 1994 rom-com classic Sleepless in Seattle where Tom Hanks’ character, Sam, watches New Year’s fireworks fill the Seattle sky… Continue Reading Stardust

Posts published in “IFA Insights”

Sailing high during Miami’s 2021 Art Week was Betye Saar’s 2019 Gliding into Midnight assemblage, making its home at the Institute of Contemporary Art. Positioned… Continue Reading Dead and Dying: Betye Saar’s and J. M. W. Turner’s Slave Ships

The history of all hitherto existing society may well have been the history of class struggle, but this struggle has been pitched against a background… Continue Reading On Labor Day Hurricanes

In early November, IFA MA student Cindy Qi interviewed Hu Xiangqian, whose work is currently exhibited at the Institute of Fine Arts, NYU as a part of the fall Duke House Exhibition chin(a)frica: an interface, on view through February 18, 2018. Hu Xiangqian (b. 1983) was born in Leizhou, Guangdong Province and graduated in 2007 from Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts. He currently lives and works in New York City. Hu’s artistic practice is grounded in performance and video works featuring an intentional amateurishness and crudeness. Notable exhibitions include the Gwangju Biennial (2014) and the Shanghai Biennial (2016). A photographic still of his durational performance piece entitled The Sun (2008) hangs in the Institute’s Lecture Hall. The interview was conducted in mandarin Chinese and later translated to English by Cindy Qi.

CQ: Having been in New York for several months now, do you have any discoveries or inspirations you would like to share? Have you decided what kind of work to make during your time here?

来到纽约这几个月你有什么启发或者发现呢?现在有没有构想出想做的作品呢?

HXQ: Yes, I have been preparing to get started in my studio. I live in Brooklyn and in my opinion, it’s a very isolated area that has nothing to do with art, but I like that place. It allows me to distance myself from all that is happening in Manhattan while also having the opportunity to be close to all of it. I really like this feeling of being able to pull away and engage at the same time.

我在我的工作室里准备啊,我现在住的地方比较远,在布鲁克林。 那个地方算是很荒凉的,跟艺术没有什么关系。但是我喜欢那个地方,所以我会在那里做作品。我还挺喜欢这种跟曼哈顿若即若离的感觉。

Contemporariness is, then, a singular relationship with one’s own time, which adheres to it and, at the same time, keeps a distance from it. More precisely, it is that relationship with time that adheres to it through a disjunction and an anachronism.[1]

– Giorgio Agamben

Although Sharon Hayes is a contemporary artist, reviewers of her work almost always discuss it in relation to American art and culture of the 1960s and ’70s. Critics such as Quinn Latimer and Paul David Young write of Hayes’s “plaintive missives [that] recalled songs from the ’60s and ’70s by Marvin Gaye and Nina Simone”[2] and that her art “speaks of a longing for the golden era of artistic and political radicalism of the late 1950s through the ’70s.”[3] During the Q&A following Hayes’s February 24, 2015 talk at the Institute of Fine Arts (part of the Artists at the Institute lecture series), Professor Robert Slifkin addressed this theme, asking the artist about any sense of nostalgia in her work: either for that period of American history, or for the radicality the era offered.

The question followed naturally from the artworks Hayes chose to highlight, which included Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA) Screeds #13, 16, 20 & 29 (2003), Everything Else Has Failed! Don’t You Think It’s Time for Love? (2007), Parole (2010), An Ear to a Sound in Our History (2011), and Ricerche: three (2013). Many of these were exhibited in her 2012 solo show at the Whitney Museum of American Art, and Hayes presented them as examples of engagement through video art. Of these five works, four explicitly reference or build upon art and events of the 1960s and ‘70s, from Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Comizi d’amore (1964) to Patty Hearst’s kidnapping by the Symbionese Liberation Army (1974). Hayes explained that, having been born in 1970, she had a “temporal” relation with that decade, but could not at the time process that moment’s politics and culture in which she finds such rich inspiration now. She told the audience that she does not mourn the loss of that era, but uses it as “the past that exists in the present,” or the “near past.” For Hayes, this “near past” has an unfinished relationship to our present moment, and sets the parameters for the questions and issues with which we still contend.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ExBCbpAHEpM

Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA) Screeds #13, 16, 20 & 29 (2003) was Hayes’s MFA work at UCLA. In it, she “re-speaks” the words of Patty Hearst on the videotapes released by the SLA, but without any of the fidelity of a reenactor, which is a purposeful distinction. Hayes explained to the audience that she finds the concept of “reenacting” problematic because such endeavors attempt to make whole the past, without its natural ruptures.[4] Instead, in the Screeds, the “notness” of the work is foregrounded: she is not Patty Hearst, it is not 1974, the camera crew is not the SLA. As Hayes stumbles through her partially memorized monologue, the audience eagerly jumps in to correct her mistakes, emphasizing the video’s disjunctures—not continuities—with the 1974 tapes. In 2006, Julia Bryan-Wilson astutely described Hayes’s approach as “investigations into the stutters of history, its uncanny reoccurrences and unexpected recyclings.”[5]

Hayes then screened Ricerche: three, a video of her interviewing Mount Holyoke students about gender- and sex-related topics, directed by Brooke O’Harra. I was surprised by Hayes’s blunt, direct, and leading questions, which contrasted so starkly with her usual careful speech, and often derailed the conversation or stymied the students. After the video, Hayes explained that the piece was formulated on director Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Comizi d’amore, and her interviewing style mimicked his, sometimes using the same questions. As did Pasolini, Hayes talked to the students in a group, “as their social selves,” and as they developed debates about feminism, identity politics, and trans issues, rifts formed: between the students who found “feminism” a welcoming label and those who didn’t, or those who saw sex as central to their identity and those who didn’t. During a lively and often provoking debate about current understandings of sex and gender, the transposition of Pasolini’s 1960s method and questions was often jarring and frustrating. And this fidelity to her source material displayed what Hayes called “disrupted time,” emphasizing, as in the Screeds, the distinctions (not the similarities) between the two contexts.

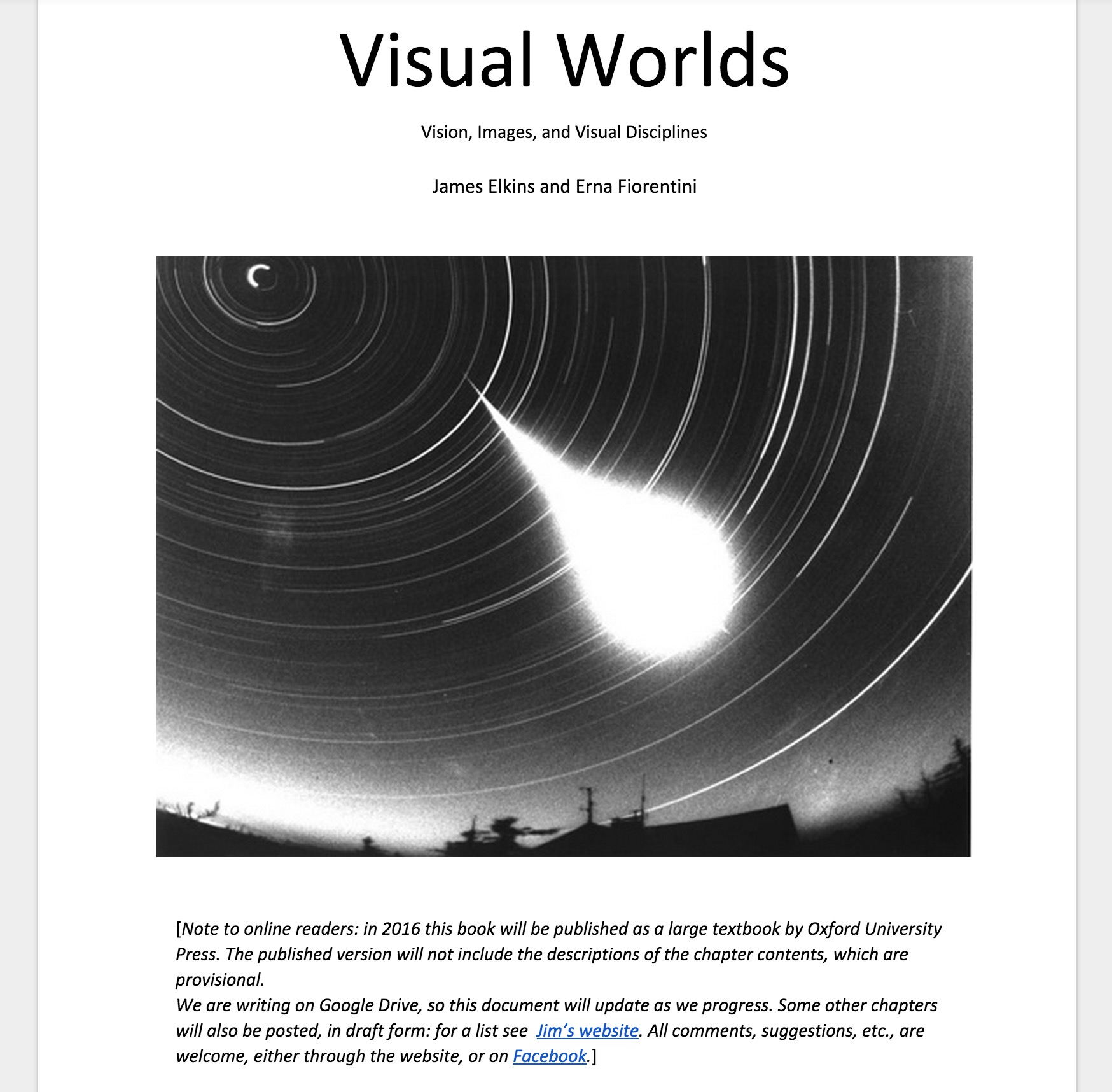

James Elkins, Professor in Art History, Theory, and Criticism at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, delivered a lecture at the Institute of Fine Arts on February 10, 2015 as part of the Institute of Fine Art’s Daniel H. Silberberg Lecture Series. The lecture, “The End of the Theory of the Gaze,” explored the shortcomings of existing theories about the gaze and presented several aspects of Visual Worlds, the book that Professor Elkins is currently working on. IFA Ph.D. Candidate Claire Brandon spoke with Professor Elkins after the lecture.

Claire Brandon: Your lecture presented the failure of the theory of the gaze in the context of the new book you are working on, Visual Worlds. Could you talk a little bit about the digital format for this project? You mentioned that you and Erna Fiorentini are writing and editing this document using Google Drive, allowing for open-sourced authorship in some instances. How does this process work? How did you decide on Google Drive as a tool?

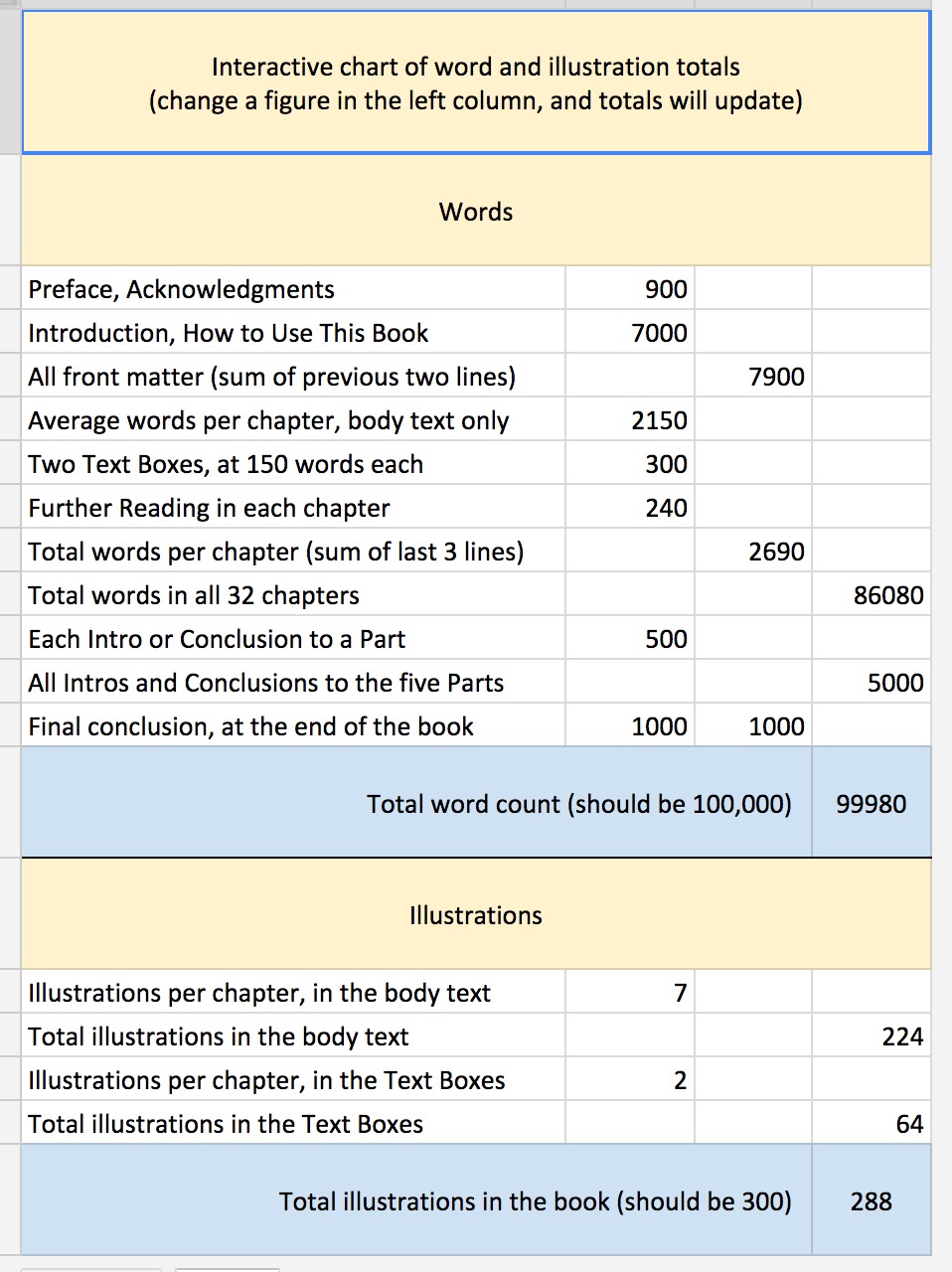

James Elkins: Well, we chose Google Drive (link here) just because it’s simple and it includes spreadsheets (which we need to keep track of word counts, illustrations, etc.). I have tried several WordPress sites, Nings (some are quite expensive), and other collaborative tools; they’re useful if you need video conferencing, separate discussion groups, etc.

The co-authoring part of the project works extremely smoothly: we have a document called “What’s new” where we exchange ideas; two spreadsheets to manage the many tasks of accumulating words, images, and arguments; a third spreadsheet for managing word counts; a document that records the Oxford Press “house style” (that’s something authors usually don’t see until the end, but we’re making our own “house style” for citations and usages).

In early February, Curatorial Assistant Ingrid Langston and IFA MA Candidate Ashley McNelis toured the MoMA galleries. Langston assisted MoMA PS1 Curator Peter Eleey in organizing the exhibition Sturtevant: Double Trouble at MoMA, which runs from November 9, 2014 to February 22, 2015. Double Trouble is timely not just in light of the artist’s recent passing, but also because it is only Sturtevant’s second American-organized solo show since the 1970s. The intervening four decades—in which Sturtevant was largely ignored by the art world—have afforded her audience the time and hindsight to catch up with her intelligently penetrating vision. Sturtevant: Double Trouble also juxtaposes traditional art historical narratives (represented by works in MoMA’s permanent collection) against works from Sturtevant’s reactionary oeuvre. The exhibition will be on view in the third floor Special Exhibitions Gallery and the fifth floor Sue and Edgar Wachenheim III Painting and Sculpture Gallery at MoMA until it heads to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles from March 21 to July 27, 2015.

Ashley McNelis: I understand that Sturtevant actively combated the use of curatorial strategies at other institutions. What was working with her at MoMA like?

Ingrid Langston: Unfortunately, I never got to meet her personally. She was working with Peter Eleey closely and was planning to come out for the installation before she passed away in May 2014. Peter went to Paris every few months to meet with her, but by the time I came on the project she was not really traveling much. So I never worked with her directly, which is a shame, but probably also made my life a lot easier. We did work closely with her daughter, Loren, too, who, along with her gallery in Paris, is the executor of the estate and the co-producer of Sturtevant’s video works.

In starting with the long hallway to the exhibition space that we were given, there is a puzzle right off the bat. It can be a challenge to draw people in and to make them understand that there’s an exhibition at the end. One of the very first pieces that Peter and Sturtevant placed was the dog, Finite Infinite (2010). It’s striking, like you’re literally running along with the dog down the hallway to the target at the end [Sturtevant’s Johns Target with Four Faces (study) (1986)]. The dog runs again and again into the wall; it’s endlessly repeating. It sets up the notion of the frustration of progress, related to how her whole project went against the idea of a straight, progressive narrative of art history.

Here, in Study for Muybridge Plate #97: Woman Walking (1966), she strides in front of the lens like in an Eadweard Muybridge, positioned in front of her own versions of Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol, and James Rosenquist. It’s a nod to photography, the most “copying” medium. It’s about action, the circulation of images and the frustration of circular motion like this wallpaper of an owl whose head keeps turning. It’s so weird—we’re pretty sure she just grabbed it off the internet for her 2013 Serpentine show. The exhibition is trying to speak to the consistency of her project. It’s almost shocking how she stuck to her guns pretty much from 1964 when she began recreating the works of other artists.

Following a thirty-two-year tenure as Director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Philippe de Montebello has been, since 2009, Fiske Kimball Professor in the History and Culture of Museums at the Institute of Fine Arts. Also in that year, Professor de Montebello became the first scholar in residence at the Prado Museum in Madrid, and, among his many other honors and awards for his contributions to the arts, was recently named to the Board of Trustees of the Prado and the Musée d’Orsay. On November 21, 2014, IFA Master’s student Jennie Sirignano sat down with Professor de Montebello to discuss his newly-published book, Rendez-vous with Art.

Jennie Sirignano: Professor de Montebello, thank you for meeting with me. In your new book Rendez-vous with Art, you mostly focus on ancient and European works of art. Was it a conscious choice to not include discussions of contemporary art?

Philippe de Montebello: We just happened to not go to certain places. I didn’t go to the National Gallery in London. I didn’t go to the Uffizi. For over two and a half years, Martin and I would call each other and say “I’m going to Florence for a conference—can you be there?” And so we happened to be in Florence, and me in Madrid because I am on the board of the Prado, and he never had more than one day, nor me more than one day, so we limited it. I would have loved to do the Musée du Moyen Âge in Paris at Cluny. I never got around to it. I could have spent a great deal of time in MoMA looking at things I love. Not contemporary, it would have been more Modern. Contemporary I don’t understand very well, but if I do a second book with him, which I don’t think I will because I don’t think it’s necessary, I would do medieval, I would do Islamic, and we would cover many of the things we haven’t. This serves in a way as a kind of travel guide for people who want to go around and look at art. I don’t know. I am not sure it serves anything.

JS: Well, you have described your decision to dedicate the majority of your professional life to museum work as wishing to “above all share my passion with others, many others.” Does Rendez-vous with Art have a similar genesis?

On December 16, 2014, Marci Kwon sat down with Alexis Lowry Murray and Delia Solomons, who co-curated the exhibition Sari Dienes at the Drawing Center. All are PhD candidates at the IFA.

MK: To begin, how did you come up with the idea for the show? And what was it like putting it together?

ALM: It was surprisingly simple. While researching Jasper Johns, I came across Sari as a side note in the catalogue for the Jasper Johns retrospective, organized by Kirk Varnedoe. Delia and I had been talking about curating a show together, and think I waited only twenty minutes before I talked to her about it. We looked up the Sari Dienes Foundation website, and were immediately interested in the rubbings she made, and the indexicality of that process. We made an appointment to go to the Foundation – we simply called their phone number – and when we got there it was instantly clear to both of us that an exhibition was the best idea. We had gone up to the Foundation open-endedly–for a moment I even thought about doing a dissertation on Sari–but we immediately knew an exhibition was best.

DS: The works looked incredible in person–really delicate and yet with this substantial scale. While examining them in the barn, we instantly pictured them on white walls in a gallery or museum space in New York, back in the urban context where she originally made these works.

MK: You first saw them in a barn?

ALM: Sari’s work is housed in a barn that is cared for by her Foundation. Barbara, the curator of the Foundation, and her husband Rip live in upstate New York where Sari used to live. Sari used to work in the Foundation’s barn, and it is literally chock-full of art.

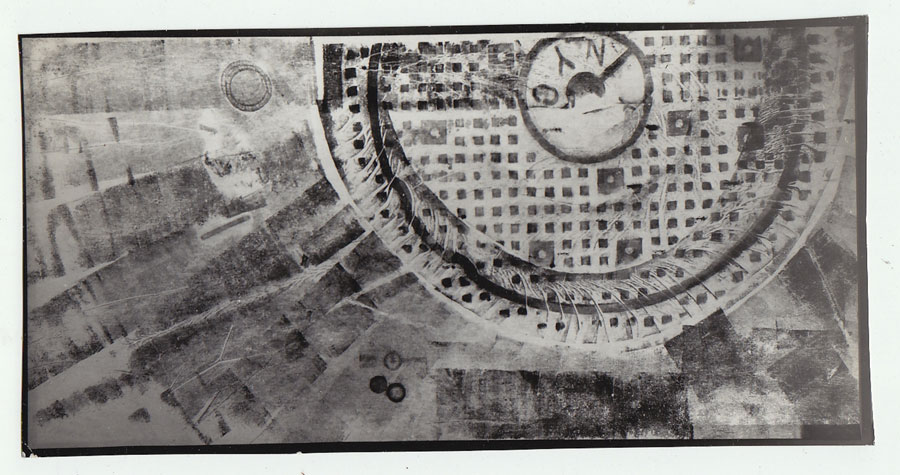

The exhibition of Sari Dienes’s work at The Drawing Center (on view October 8 to November 16, 2014) highlighted the artist’s innovative and experimental approaches to mark making in her large-scale rubbings of New York City streets from the 1950s. On November 13, the curators of the exhibition (and current PhD candidates at the IFA), Alexis Lowry Murray and Delia Solomons, led a public tour that introduced Dienes’s work by examining the dynamic interplays of processes and textures in her drawings. During the tour, Solomons and Lowry Murray gave context to Dienes’s practice by underscoring her creative exchanges with contemporaries such as Jasper Johns and John Cage. Following the tour, artists Alison Knowles and Gillian Jagger talked with NYU’s Julia Robinson about their mutual interests in using found forms and textures from natural and urban landscapes in their work.

Sari Dienes (1898—1992) was born in Hungary and was a student of Purists Fernand Léger and Amédée Ozenfant. By 1936, she was Assistant Director of Ozenfant Academy of Fine Arts in London. She moved to New York City in 1939 where she soon befriended artists both established (Mark Rothko) and emerging (Johns and Cage, as well as Ray Johnson, Robert Rauschenberg, and others), many of whose names are listed in pages from the guest book from her studio. On Thursday night, Lowry Murray and Solomons emphasized Dienes’s willingness to experiment with found materials and new processes, and her subversive recoding of established notions of the authorial gesture, qualities that are as important today as they were to Dienes and her contemporaries as seen, for example, in the work of Ray Johnson, Rachel Whiteread, and Rirkrit Tiravanija.