Vanmechelen is an internationally acclaimed conceptual artist whose work focuses on issues pertaining to identity, biodiversity, globalization, and human rights. A self-taught artist, painter, and performer, Vanmechelen uses animals as metaphors for human beings to explore themes of hybridization and domestication. Reflecting on his previous exhibitions at the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence and Fondation Linda et Guy Pieters in Saint Tropez. In this interview, Vanmechelen joins Lara Xenia Mashayekh in conversation about his oeuvre.

LXM: What first sparked your interest in biodiversity?

KV: As a young child, I became fixated by chickens because they are domesticated creatures. For me, the precarious struggle of life and death during the process of hatching is crucial as a breakthrough—akin to a space shuttle or artistic experiment. The chick is first confined to the structures of an egg, then to an incubator where it grows, and later, to a cage to age. If you look at society, we confine ourselves to the structure of a house until we grow up, migrating from one cage to another until we die. Thus, domestication relates to how we coexist.

When I was 17, I began making chicken sculptures that sought to distill the idea of freedom. I realized that the real cage was the chicken because mankind domesticated the animal. All chickens biologically descend from one Himalayan creature, the Red Junglefowl, but mankind’s domestication of the animal limits its genetics, becoming a cage of our thoughts. To address this danger, I crossbred a Belgian chicken with a French chicken on the border between the two countries in an exhibition curated by the acclaimed curator Jan Hoet. I noticed that the Le Poulet de Bresse breed from France has blue legs, a white body, and a red crest, reminiscent of the French flag. Similarly, the fluffy chicken from China is characteristically “silky” and the Denizli Horouz from Turkey produces long crower sounds that are reminiscent of those chanted from minarets. Thus, by limiting the creatures to the dynamic of inbreeding, we kill the possibility of evolution.

In 1999, I founded the Cosmopolitan Chicken Project [CCP], a research project for the hybridization of chicken breeds. The CCP aims to demonstrate how the chicken is a mirror of the human being by sparking reflections on the impacts of globalization, racial interbreeding, genetic manipulation, and animal and human behavior. The project made for a very sustainable chicken that is fertile, immune, and diverse, and provided a sustainable food that could support rural areas. As such, I began to collaborate with scientists from Ethiopia, Zimbabwe, and England and got inspired by the merits of hybridity, as opposed to pureness and monoculture.

LXM: It’s fascinating that your interest in chickens stems from an impetus to address domestication and rights.

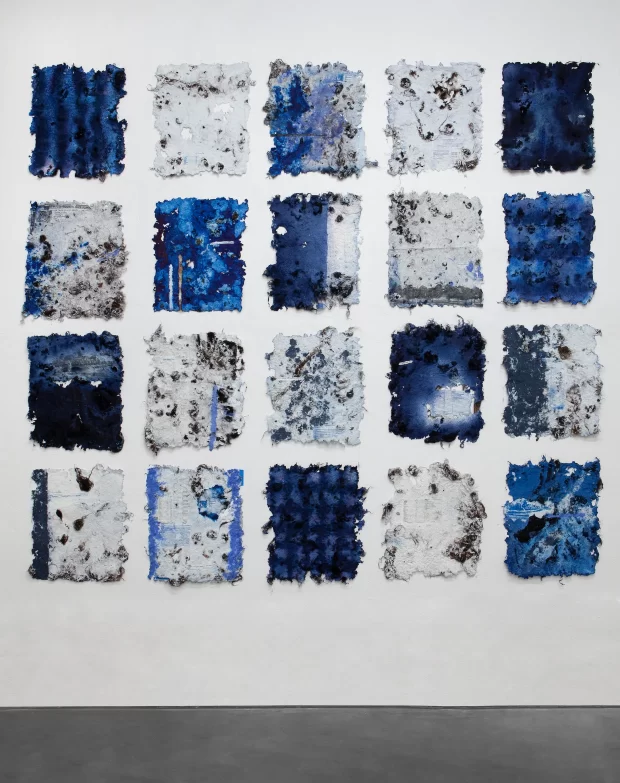

KV: Yes. As with my other work, like the Collective Memory series, I often relate humans to animals, proclaiming that nature is a human right. I feel that art is a human right, since art has the ability to speak before actions do and offers a type of creative freedom. Art points out conflicts, can educate others, and ignite a desire to create future projects that can help society.

LXM: I was very taken by the grand mosaic of you at the Fondation Linda et Guy Pieters in Saint Tropez, where you similarly sport a chicken pelt. Could you please take me through your tile-making process and choice of subject matter?

KV: That exhibition was my first foray into making hand-painted tiles. I was inspired by the region of Southern France and by my time living in Porto, where I made the pieces. There, I shifted away from making benign scenic scenes in favor of using traditional techniques. Therefore, I believe that this kind of scenery has to be something which is fixed.

LXM: Would you also consider your Medusa to be “fixed”?

KV: Absolutely. Historically, Medusa was perceived as a nefarious figure, but my Medusa conveys a different story. She is a powerful healer, for the snakes that adorn her relate to poison, but low doses of venom were used as the first forms of medication. I morphed the snake’s heads into chickens to allude to chicken’s evolution from reptiles. As a changing figure, Medusa expresses the possibilities of the future. Using tiles allowed me to explore the notion of hybridity, but also offers the idea of eternality. Crucially, the grid format enabled me to create an authentic and geometric dimension to the work. All of my works have three-dimensionality. Tiles therefore invite the “fixed” aspect that coalesces with reality in ways that paintings simply cannot.

LXM: When you were sculpting the Medusas, did you ever envision them flanking Caravaggio’s painted shield of the same mythological figure?

KV: No, never. I have to celebrate the Uffizi’s director Eike Schmidt for his bravery in bringing such works to the Uffizi as fully-integrated contemporary artworks in the museum.

LXM: Speaking of the Uffizi exhibition, what was the significance behind your shamanistic self-portrait Ubuntu?

KV: Ubuntu is a very important concept in South African philosophy, meaning “I am because we are” in Bantu. I wore a pelt that is composed of various chickens, to allude to the everpresent hybridity of species and the need to embrace diversity. I made a transparent mask to cover my face. Since it cannot hide my visage or soul, the mask metaphorically suggests that we are the Other. If one looks through the mask, one distortedly sees oneself. It is the universal bond of exchange and sharing that unites us together as humanity because we are nobody without others. One connects as a human being with the surroundings of animals and nature, but also with the Other.

LXM: That’s fascinating. What did you hope people would walk away with when viewing your works in the Uffizi galleries?

KV: The Uffizi was important and its surroundings speak for itself. During the Renaissance, artists were concerned with society. The Uffizi’s ceilings reflect this, for each is dedicated to different professions in order to promote a new way of thinking about society. By putting my works between those by Caravaggio, Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and the Old Masters, it sparks a new dialogue. To me, that was just as rewarding as it would be to speak at the United Nations because it is a continuous and open conversation. With all my work, I aspire to go to the essence of life and especially to domestic life because we went too far with domestication. For over 100 years, we were busy with destruction and were thinking that it was construction. Yet, even in science, there is the old, erroneous adage, “When nature goes wrong, we have to correct it.” Nonetheless, COVID showed us that we are not immune to the whims of the natural world.

LXM: When you made the tigress piece Domestic Violence, did you initially think of it as a metaphor for nature?

KV: All of my philosophy comes from the art that I create. Domestic Violence is a very important work that depicts a tigress tamely resting on a carpet. A glass sword stabs the tigress. It is immune to the pain, and is thereby surrounded by transparent swords. Such seemingly painless harm is symbolic of how human beings commit violence against society and nature. The predator becomes the prey. It’s the same as how we are fearful when we see a reptile, but are unphased when we see a chicken. The harmlessness of a small cat lets us act however we please, but the unpredictability of a tiger poses a threat. As soon as the tigress’ pain tolerance is exceeded, the tigress will attack, just as nature will strike back if we continue to destroy the planet.

LXM: Lastly, what is something that you want the world to know about?

KV: WHOOH! [laughs] That is a big question. I would like the world to remember that human beings are one species and that it’s not about race. That is why the chicken project is so vital to my practice. It’s a pity that the diversity that we create in our cultures is treated as a barrier for understanding each other. I hope my work inspires viewers to recognize this.

Click here to learn more about Vanmechelen’s foundations, projects, and upcoming exhibitions.

Artworks © Koen Vanmechelen

Koen Vanmechelen is an internationally acclaimed conceptual artist whose work has been shown in over 80 solo shows and 220 group shows worldwide, including at the Galleria degli Uffizi, the Victoria & Albert Museum, The National Gallery, and the Museum of Arts and Design in New York. He has instituted five foundations and received an honorary doctorate from the University of Hasselt, the Golden Nica Hybrid Art Award (Linz), and the Global Artist’s Award (Venice).

Lara Xenia Mashayekh is an art writer with an interest in global modern and contemporary art. She holds a degree in art history from the University of St Andrews in Scotland and attends the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University.

Be First to Comment