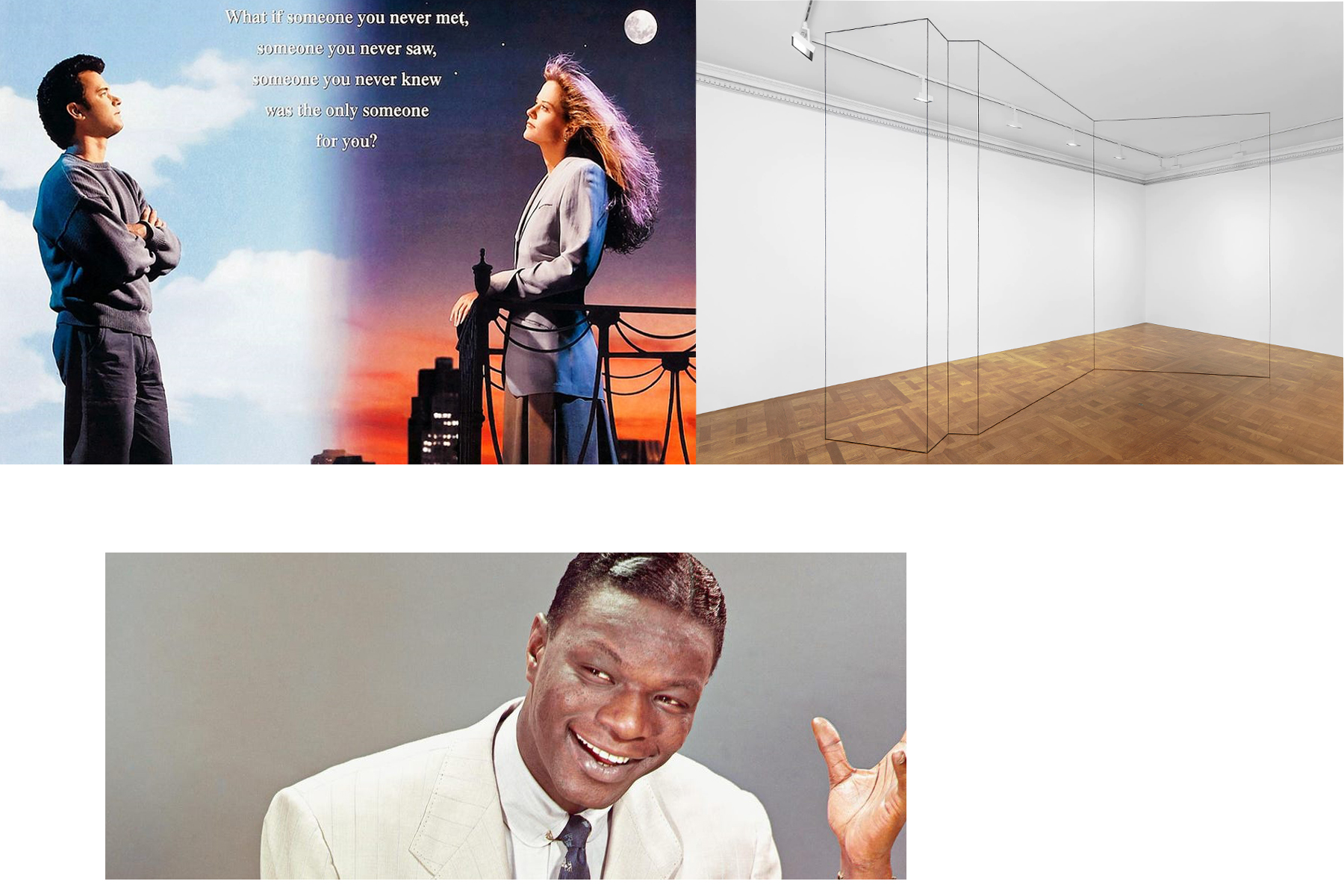

There is a scene in the 1994 rom-com classic Sleepless in Seattle where Tom Hanks’ character, Sam, watches New Year’s fireworks fill the Seattle sky after taking his son, Jonah, to bed. Hanks plays a heartbroken widower who becomes a national heartthrob after sharing his story on a radio station, catching the attention of “the perfect woman,” Meg Ryan. The fireworks scene shows up within the first 30 minutes of the movie, before Hanks and Ryan have met, and is underscored by the smooth sound of Nat King Cole’s voice singing the jazz standard “Stardust.” Trumpet-heavy and slow, the song is not an easy one to sing, though this didn’t stop me from trying as I listened to the soundtrack almost every day for 2 years during my hour-long commute to college. I spent more than ten hours of my week in that gold, 2001, 5-speed Saturn Ion cruising down Interstate 70 in central Ohio, my music options limited to the small CD collection that had been scattered across the back seat, footwells, and trunk for years. My parents probably bought the Sleepless in Seattle disk around the same time they bought the car, but it was mine in the way I could anticipate every transition between songs, every note, and every word.

Though I dream in vain

In my heart it will remain

My stardust melody

The memory of love’s refrain

Without listening, I can still perfectly hear Nat’s voice draw out “refrain” at the end of the song like he’s pushing a soapy bubble through a plastic, o-shaped wand. The wand is the song, and his voice is the bubble, but it never pops. Bouncing along with such ease and clarity, he deceives his listeners into thinking his job is effortless. His pitch is perfect, his voice comforting and melancholic and hopeful all at once.

***

I reflected on these memories on an unusually warm evening in October, 2022. It was my boyfriend Nick’s 25th birthday, just over a year after our move to New York from Columbus, and I wanted to surprise him by arranging for an autumn walk through Central Park followed by a trip to the Dia: Chelsea gallery on 27th street. A frantic google search to find a not-too-long but not-too-short event in the city had led me to Dia’s “Poetry &” series, a recurring event that asks a selected poet to choose a collaborator across disciplines to present work with. Tonight’s showcase brought the poet Jon Sands into conversation with jazz trumpetist Riley Mulherkar. This was perfect because poetry and jazz are my favorite things which is another way of saying I love mediums that do the difficult and therapeutic work of expressing feelings without explicitly saying what they are. Despite this, Nick and I had been to enough artist talks and public readings to know that this could go south quick. I leaned over and whispered, “If this is weird, we can bail.”

The collaboration started outside, in the unreasonable warmness and in front of the gallery, where Riley and Jon stood on separate orange boxes positioned low to the ground. Before they began, Nick and I were passive-aggressively told off by a woman who claimed we were “blocking her view” (we weren’t) which upset and disarmed me. As I considered letting this ruin my night, Riley and Jon began to perform simultaneously. They worked in perfect harmony as Jon read aloud from his book and Riley matched the cadence of the poet’s voice with his trumpet. It struck me that this was not, in fact, two performers performing, but friends having the kind of animated conversation you can’t help but overhear on the Subway. The irritation I had felt a minute ago peeled away as I stood in awe of just how synchronous the world felt in that moment, the familiar sounds of sirens and distant shouting and wind harmonizing with voice and instrument.

When we moved inside the gallery, Jon shared another poem that mentioned a childhood in Cincinnati surrounded by Denny’s and Waffle House diners and teenage years filled with anxiety, cheap beer, and trying. Nick and I exchanged glances: though our New York friends know that we are from Ohio, we’re not convinced they know what this means. They cannot know what it is to spend weeks in the summer without seeing the sun while surrounded by mostly flat cornfields, the only golden thing around. They can’t know that to drive back to Cleveland from Columbus, or to Cincinnati from Indianapolis, or to Columbus from Pittsburgh after a concert means you won’t get home until 2am and each time you swear up and down that you won’t do it again. They may not know about the “Hell is Real” billboard on the side of I-71, or that most billboards around the state say something about marriage, abortion, community college, or God. But Jon knew.

His familiar mid-western humor (dry, self-deprecating, but somehow still incredibly nice) felt like a friend as we all laughed and then thoughtfully “hmmmmed” in unison. Finally, it was Riley’s turn to take a stand up front on his own: no poems, no voices, just the sound of his trumpet and the shuffling of chairs and feet as we settled in, expectant. The overhead lights dimmed and several turquoise blue spotlights flicked on piercing Nick and I as we lay slumped in bean bags at the edge of the room. From our vantage point, we could see Riley and Jon’s profiles as well as the faces of most participants who chose a more traditional seating arrangement in the center of the space.

Riley started soft, pushing more air than sound through the trumpet, but I immediately recognized the air to be the opening notes of Stardust. I began to weep. The trumpet got louder as Riley gained confidence, filling the negative space of the room as we all sat, breathless, clinging to something we could not yet name. I wept harder. I understood that I was sitting in a bean bag in Chelsea, New York, but part of me was also rattling down the highway in my gold Saturn at sunset, feeling sleepy and uncertain about my life, listening to Nat King Cole croon. The music washed over me, the turquoise lights drowned me, and I found myself swimming in my own water.

Digging for a molecule of control, I looked around the room to see how others were choosing to respond, though my own response had not felt like a choice. I noticed José Olivarez, a prolific poet and curator of the event, sitting bent forward with his hands spread and palms facing up. Having been a church attendee for my whole life, I recognized the gesture as one of worship. More specifically, this motion (hands low and close to the abdomen) signals that the worshiper is opening themselves up to receive something: a word, a blessing, a moment of peace. If any part of me had felt anxious at reacting so strongly to the beauty of the music, I may have felt relief knowing I was not the only one. But I only felt comfort in what I shared with José and Jon and Nick and the others in the room who were clearly forgetting everything else to focus solely on Riley.

When the music ended, and Jon read another poem or two, the lights remained dim as both artists thanked us and then invited us to read from iphone images of Jon’s favorite poems projected onto the walls of the room. My eyes puffy and tear stained and shameless, I approached José and thanked him for creating such a space. “I noticed the way you had your hands open during Riley’s solo,” I added. He said he had seen me crying and felt moved to respond with a physical action too. Under different circumstances, I might have been embarrassed at having been seen like that, or I may have waived the comment away to make myself small, unimportant. Instead, I told him about the Sleepless in Seattle soundtrack and church and how unexpected my tears were. He said though he’s not religious, he was struck by the need to open his hands in worship. I nodded. I knew what he meant.

***

Several years ago, as a sophomore in art school, I read an article by contemporary artist Andrea Fraser that changed how I accept art. Not how I view it, but how I choose to approach it and let it approach me. I admit that, despite having only spent several years pursuing an education in the arts, I have become jaded by the bureaucracy, inaccessibility, and problematic standards set forth by its institutions. I think many of us have been. When you know what to look for, you tend to find it, and my experiences in art museums are often a mix of intense admiration and criticism. When I attend events such as the one at Dia, such criticism is a sword hitched to my side, ready to strike. Fraser’s article, Why Does Fred Sandback’s Work Make Me Cry? reminds me that to be moved by art is to be human. How can I desire to make art more accessible if I am not first in total awe of it and deem it a worthy thing for others to love too?

Fraser had seen artist Fred Sandback’s truly minimal sculptures (though, according to Sandback, not capital “m” Minimalist) at Dia: Beacon just a month before the artist passed away in 2003. The negative space between his simple, yet densely conceptual, acrylic string masterpieces gave Fraser the space she needed to have an emotional reaction and she began to weep. In her essay, she tells us that tears are the only clean thing to exit the human body, and those produced when one is faced with absence or loss work to soothe the eye as it attempts to fill in the gaps. The loss of material in the string sculptures became a metaphor for what Fraser had lost herself. Coupled with the beauty and tenderness of the work, she soothed herself through tears; there was no other option.

Like Fraser, and Jon, and Riley, and José, and Nick, and everyone, I have lost things. I lost my Saturn to a cobblestone street in Columbus when the axle snapped in two. I lost the Sleepless in Seattle CD when I moved to New York to pursue my dream to become a curator of modern and contemporary art. I lost bits of blank skin to a tattoo of a Fred Sandback sculpture, printing the thin lines of black and blue onto my body forever. I lost pieces of myself when I left Ohio. But listening to Stardust in a room full of people whose names I will never know, I got some of it back.

***

Grace Oller is a curator, art historian, and poet in the second year of her Master’s degree at the Institute of Fine Arts. Her research focuses on modern and contemporary art and museum studies, particularly focusing on work that takes up space like performance and sculpture.

Be First to Comment