Contemporariness is, then, a singular relationship with one’s own time, which adheres to it and, at the same time, keeps a distance from it. More precisely, it is that relationship with time that adheres to it through a disjunction and an anachronism.[1]

– Giorgio Agamben

Although Sharon Hayes is a contemporary artist, reviewers of her work almost always discuss it in relation to American art and culture of the 1960s and ’70s. Critics such as Quinn Latimer and Paul David Young write of Hayes’s “plaintive missives [that] recalled songs from the ’60s and ’70s by Marvin Gaye and Nina Simone”[2] and that her art “speaks of a longing for the golden era of artistic and political radicalism of the late 1950s through the ’70s.”[3] During the Q&A following Hayes’s February 24, 2015 talk at the Institute of Fine Arts (part of the Artists at the Institute lecture series), Professor Robert Slifkin addressed this theme, asking the artist about any sense of nostalgia in her work: either for that period of American history, or for the radicality the era offered.

The question followed naturally from the artworks Hayes chose to highlight, which included Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA) Screeds #13, 16, 20 & 29 (2003), Everything Else Has Failed! Don’t You Think It’s Time for Love? (2007), Parole (2010), An Ear to a Sound in Our History (2011), and Ricerche: three (2013). Many of these were exhibited in her 2012 solo show at the Whitney Museum of American Art, and Hayes presented them as examples of engagement through video art. Of these five works, four explicitly reference or build upon art and events of the 1960s and ‘70s, from Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Comizi d’amore (1964) to Patty Hearst’s kidnapping by the Symbionese Liberation Army (1974). Hayes explained that, having been born in 1970, she had a “temporal” relation with that decade, but could not at the time process that moment’s politics and culture in which she finds such rich inspiration now. She told the audience that she does not mourn the loss of that era, but uses it as “the past that exists in the present,” or the “near past.” For Hayes, this “near past” has an unfinished relationship to our present moment, and sets the parameters for the questions and issues with which we still contend.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ExBCbpAHEpM

Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA) Screeds #13, 16, 20 & 29 (2003) was Hayes’s MFA work at UCLA. In it, she “re-speaks” the words of Patty Hearst on the videotapes released by the SLA, but without any of the fidelity of a reenactor, which is a purposeful distinction. Hayes explained to the audience that she finds the concept of “reenacting” problematic because such endeavors attempt to make whole the past, without its natural ruptures.[4] Instead, in the Screeds, the “notness” of the work is foregrounded: she is not Patty Hearst, it is not 1974, the camera crew is not the SLA. As Hayes stumbles through her partially memorized monologue, the audience eagerly jumps in to correct her mistakes, emphasizing the video’s disjunctures—not continuities—with the 1974 tapes. In 2006, Julia Bryan-Wilson astutely described Hayes’s approach as “investigations into the stutters of history, its uncanny reoccurrences and unexpected recyclings.”[5]

Hayes then screened Ricerche: three, a video of her interviewing Mount Holyoke students about gender- and sex-related topics, directed by Brooke O’Harra. I was surprised by Hayes’s blunt, direct, and leading questions, which contrasted so starkly with her usual careful speech, and often derailed the conversation or stymied the students. After the video, Hayes explained that the piece was formulated on director Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Comizi d’amore, and her interviewing style mimicked his, sometimes using the same questions. As did Pasolini, Hayes talked to the students in a group, “as their social selves,” and as they developed debates about feminism, identity politics, and trans issues, rifts formed: between the students who found “feminism” a welcoming label and those who didn’t, or those who saw sex as central to their identity and those who didn’t. During a lively and often provoking debate about current understandings of sex and gender, the transposition of Pasolini’s 1960s method and questions was often jarring and frustrating. And this fidelity to her source material displayed what Hayes called “disrupted time,” emphasizing, as in the Screeds, the distinctions (not the similarities) between the two contexts.

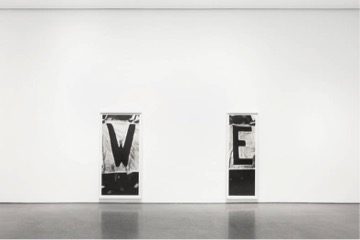

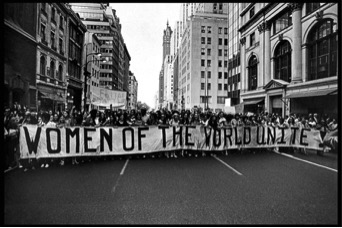

A more recent work of Hayes’s, on view at Andrea Rosen Gallery through April 25, is another example of her fragmenting re-presentation (what she calls “re-speaking”) of social movements of the past. In a small group exhibition of Hayes, Tony Lewis, and Adam Pendleton, Hayes is represented by two 2015 pieces: W and E. Both are silkscreened photographs of portions of a banner carried in New York during the 1970 Women’s Strike for Equality that read “WOMEN OF THE WORLD UNITE!” The national strike, a major event of feminist and women’s history, was organized by NOW president Betty Friedan and took place on the 50th anniversary of American women’s suffrage. Hayes has isolated a “W” and an “E” from the word “women” in a photograph of the protestors. Slightly smaller than life-size, the works are hung low so that they approximate where such a banner would drape if carried by marchers in the gallery. The white space around the two works seems melancholic. Many of the protestors captured in the photograph, and the entirety of their environment, have been excised, although the two silkscreens seem to be placed in correct spatial relation to each other as if the entire image had first been blown up and affixed to the wall, then cut away.

These banner fragments mirror the fragmented feminist conversation today, which has splintered between celebrity iterations (think of Beyonce’s “FEMINIST” backdrop at the 2014 VMAs and the countless “[So-and-so] [is/is not] a feminist!” articles), radfems, intersectional feminists, egalitarians, and many other groups. The seeming unity of this historical moment of early feminism—seeking global solidarity—now rings naïve, ignoring and foreshadowing as it does queer and genderfluid involvement with feminism, white feminism’s imperialism and exclusions, and disagreements between American forms of feminism and versions such as womanism from other countries.

The Women’s Strike for Equality took place the year Hayes was born, but its relevance, forty-five years later, is why it is part of our “near past.” The questions and issues raised by the tens of thousands of people who marched down Fifth Avenue are still with us today, debated on legislative floors, over dinner tables, and in the streets, and Hayes’s work is a thoughtful response to the legacy of that strike. She foregrounds the ruptures in our relationship to history, thwarting nostalgia by insisting on fractured, incomplete re-speakings of the past, and provoking frustration at these fragments of history: the verbal slips of the Screeds, the disruptive questions of Ricerche: three, and the negative space of W and E.

In this way, Hayes, whom critics sometimes insinuate is a past-looking artist, is ultimately contemporary in an Agambenian sense. In her lecture at the IFA, she demonstrated how she “adheres to” our own time “through a disjunction and an anachronism”—Hayes looks at the obscurity of today, and reads it through historical gap. As Agamben wrote, “the contemporary is not only the one who, perceiving the darkness of the present, grasps a light that can never reach its destiny; he is also the one who, dividing and interpolating time, is capable of transforming it and putting it in relation with other times. […] It is as if this invisible light that is the darkness of the present cast its shadow on the past, so that the past, touched by this shadow, acquired the ability to respond to the darkness of the now.”[6] The near past of the 1960s and ‘70s, touched by the shadow of our present, responds to “the darkness of the now” in Hayes’s re-speaking of its breaks, its slips, and its stutters.

___________________________________________

[1] Giorgio Agamben, “What Is the Contemporary?,” in What is an Apparatus? and Other Essays, translated by David Kishik and Stefan Pedetella (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2009): 41.

[2] Quinn Latimer, “Sharon Hayes,” Modern Painters (December 2007–January 2008): 92.

[3] Paul David Young, “Time for Love: Sharon Hayes at the Whitney,” Art in America (online), 27 June 2012, accessed 29 March 2015, http://www.artinamericamagazine.com/news-features/news/sharon-hayes-whitney/.

[4] In a discussion at the MoMA Contemporary Photography Forum on January 12, 2015, Hayes discussed similar reservations she had about the 2014 Pier 54 exhibition which was “conceived as a tribute to and reaction against” the 1971 Pier 18 exhibition curated by Willoughby Sharp. She found aspects of the High Line Art project troubled by both nostalgia and the attempt at “correction.” Some of Hayes’s comments can be found in the MoMA video from 1:02:30 to 1:05:30.

[5] Julia Bryan-Wilson, “Julia Bryan-Wilson on Sharon Hayes,” Artforum (May 2006): 278-9.

[6] Agamben, “What is the Contemporary?,” 53.

Be First to Comment