On April 27, 2015, IFA PhD candidate Anne Wheeler and IFA MA alumna Sarah Zabrodski sat down to discuss the Solomon R. Guggenheim’s current exhibition, On Kawara—Silence. Wheeler is the assistant curator of the exhibition. Zabrodski blogs at emergingartcritic.com.

Sarah Zabrodski: On Kawara proposed most of the exhibition sections and was a close collaborator in the early stages of exhibition planning. What was it like working with the artist?

Anne Wheeler: Senior curator Jeffrey Weiss met On Kawara in 2005, in the process of acquiring the painting Title (1965) for the National Gallery of Art, so he had a relationship with Kawara before approaching him in October 2011 about doing the Guggenheim show. I came onto the project full time in April 2012, and worked for about a year before meeting Kawara himself. We first met almost two years ago to this day, on April 28, 2013—a day I remember clearly—a Sunday. Kawara sent Jeffrey and me a map of a park, with a dot drawn in the location where we were to meet him. We went, and we waited, and finally he came walking toward us, and brought us to a picnic table where we sat and talked with him and other members of his family until the sun went down.

Kawara was very deliberately not a public figure—he was infamous for his refusal to grant interviews, show up for openings, or make public appearances. He told us early on: “I am an artist that never made any public statements,” and we always tried to be extremely respectful and protective of this choice, and of his privacy. Jeffrey took Kawara on a walk-through of the museum early in the process, and we brought him models of the Guggenheim and maquettes of his Date Paintings and other work to help him conceptualize the exhibition within the space without actually having to be there. We always measured what was worth bringing to him, what was worth asking.

Our meetings involved a lot of exhibition planning and talk about the facts of each series—how and when certain artworks were made, or what they were made for—but ultimately the meetings turned out to be more conversational than strictly business. We would go in with questions about, say, where to place a certain Date Painting, but we would end up discussing cave paintings, gravity, the role of art throughout time, the history of human consciousness—really big topics, and his opinions were quite profound. After each meeting, I’d leave thinking, “What was that?”—and then as a researcher, to always have these new “assignments” was such an education for me.

As far as the artwork, though, we never talked about why—“why” questions were not discussed. It’s been one of the funny and difficult things about giving tours, responding to the why questions: “Why these newspapers? Why the red, blue, and gray? Why this or that?” I can say all of the things that I think about the work, but I can never reference anything he actually said.

SZ: What was your impression of Kawara as a person and artist?

AW: Kawara was really interesting and mysterious—a cipher in a lot of ways—but he was also very humorous. He was always kind of playing with you—through puns, through word games. In not revealing everything to us, he made us do a lot more work, but that extra work really helped us understand his art, and gave us some authorship. We had to do a lot of tracking, often almost reversing his processes; it was all like a big game. I can’t say that I figured him out, certainly, but the process of putting together the show and then seeing the work in it has opened up so many opportunities for thinking about the material in different ways—and not just for me, I hope. I think that Kawara’s silence about everything actually creates a sort of openness in his work that just doesn’t exist with other artists. No matter what, your experience of his work is always your own.

SZ: How did his death on June 27, 2014 affect the planning and execution of the exhibition?

AW: We were deep into catalogue production and editing phases at the moment of Kawara’s passing, and we were just beginning to receive the physical artworks—so it was a time in which, in many ways, we felt Kawara to be very much “still alive.” So it was especially strange for us, and difficult to find a proper tone for the catalogue and, ultimately, the exhibition to convey. We had to acknowledge Kawara’s passing, of course, but in no way did we want to make the tone funerary or even biographical. Because the crucial elements were already in place, we chose to stick with what we had planned together. For the exhibition, this meant, for example, keeping only the paintings that he had already explicitly chosen, though he’d also intended to add more recent ones. And for the catalogue, we retained his preferred biographical format. In previous Kawara catalogues, his biography is listed as the number of days he was alive up until the opening day of the show. For our publication, we listed the number of days in his life in total: 29,771 days.

SZ: One of the things that struck me in the exhibition is the relationship between individual works versus the whole of a series. Particularly with projects as extensive as the postcard series (I Got Up), which were sent to dozens of people. What was the process of obtaining loans like for this exhibition?

AW: For I Got Up, our goal was to exhibit postcards from as many possible different people and places—where Kawara was sending to and from—and from every year Kawara was making the series. Unlike some mail artists in the 1960s, Kawara sent postcards without intending that they be returned to him. This meant we had to go out and find them ourselves. The postcards had been featured in a number of previous exhibitions, as well as a series of books by Michèle Didier, which we used as a resource. Kawara also kept records of the addressees, but he only documented names, and often just first initials and last names, so we still had to go looking for people. It was an interesting process, seeking these works out—often cold-calling people—asking for these cards, reminding people about lives they once had. We made a lot of great connections this way, though people were not always immediately open with their stories. Often they would call back to recount their memories to us, and it was like we were leading them back on this path that we as curators were also taking.

SZ: In the 1950s Kawara earned acclaim in Japan for his surrealistic drawings and paintings. Did you ever consider including examples of these works in the exhibition? Are there any other series or types of works that were not included in the exhibition?

AW: We did consider including work from 1950s, especially when the exhibition idea was to create a retrospective. But Kawara wanted the exhibition to only represent his work after he left Mexico, which marked a real shift in his career. We mention in the catalogue how, when arriving in Paris in 1963, Kawara was considering giving up art to open a travel agency; he changed his mind only after stopping to see the prehistoric cave paintings of Altamira on a trip back from Toledo. He was struck by that moment in history when humans became conscious of the universe—it was art without prejudice, without the invasion of language. And I believe because of this split in his thinking about art, he felt the art he made thereafter was completely separate from the art he made before—like nothing he made before mattered to him, and that’s why he chose not to include it here. While at first we were sorry to not be able to include all of Kawara’s work, ultimately I’m glad we didn’t; there’s just really no place for it, physically or conceptually, and I believe the exhibition is much more cohesive without it. Instead, we included a lot that hasn’t been shown before, particularly process materials. While many exhibitions have shown parts of Kawara’s work, none have cut through all the different types of series the way this exhibition does. It was important for us to bring everything together to help people make the connections between the series, and to represent Kawara’s work as fully as possible.

SZ: What were some of the challenges of installing On Kawara—Silence?

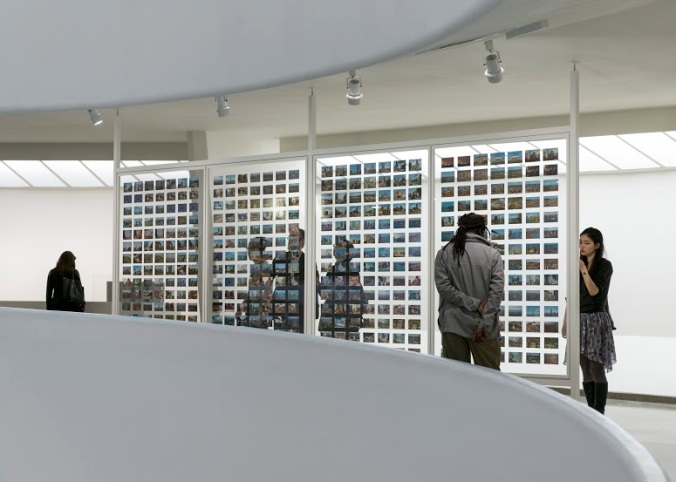

AW: For me personally, the installation of the postcard panels was quite challenging to coordinate—we had a giant spreadsheet that we used to arrange the cards chronologically, but we often didn’t have images, exact dimensions, or even exact dates in advance, so there was a lot of unknown information. We didn’t get the postcards all at once, and because we had to mount them as we received them from lenders, the mounting didn’t occur in order. Never knowing exactly what we would receive or if something would be missing and leave a gap in a panel gave me a lot of anxiety in the months leading up to the show. But I was lucky in all of this to be working with amazing people. The exhibition design and installation teams at the Guggenheim are brilliant. The challenges they face related to the building alone are so unique—the slant of the ramp, the curved walls that go up and out—adjustments during installation that are possible in other museums just aren’t here, yet they still make everything happen with such beauty and grace. I am endlessly impressed with the talent here.

SZ: Did anything change over the course of installation from what was initially planned?

AW: Not really—although some ideas were abandoned, like having one bay that included everything from a single day in Kawara’s life, or broadcasting the One Million Years reading throughout the museum. Ultimately that one didn’t quite seem in keeping with an exhibition called “Silence.”

SZ: What do you think about the relationship between the spiral architecture of the Guggenheim and Kawara’s oeuvre?

AW: We thought constantly about the architecture of the museum when designing the show. The building is all about the merging of aesthetic experience and physical movement, and Kawara’s work is often about that too, about travel in general and movement through space and time. In the Guggenheim, your movement is directed by the spiral ramps, which, in a way, become an analogy or metaphor for the passage of time.

We were told, not by Kawara himself, of course, but by people who knew him throughout his career, that he’d said the Guggenheim was the museum he most wanted his work to be exhibited in. He was excited about the building and the relationship of his work to the building even before the genesis of this exhibition.

SZ: I noticed that most of the Date Paintings are displayed in chronological order as you ascend the spiral. The exception is the final series 48 Years, which is installed in reverse chronological order. How did you decide on that arrangement?

AW: We wanted people to be able to go either direction through the show, to suggest that it’s possible to experience Kawara’s work both ways, and to make it something without a beginning or end. Between Ramp Five and Ramp Six is where the chronology reverses; you go from the Moon Landing paintings, which are about the expansion of human consciousness into space, into One Million Years, Ten Thousand Years, 100 Years Calendars, and then 48 Years—from a really broad view of time and space into something that is much more specific.

SZ: Have you encountered any reactions to the show or Kawara’s art that have surprised you?

AW: People have asked me if this is performance art and if Kawara’s works are documents of a performance; thinking about that possibility led me to focus more on the “chapter” titles Kawara came up with for the different sections of the show. One such title is Everyday Meditation, on Ramps One and Two, which includes the ninety-seven paintings Kawara painted in the first ninety days of 1970. The word “meditation” suggests, perhaps, that maybe the work was more about the painting process rather than a painting as an object—that is, painting as a verb, versus painting as a noun. Obviously Kawara was very meticulous about what he created, but as an “everyday meditation,” could it have been more about the time spent creating the object rather than the object itself?

In leading a tour of the show, the artist David Reed pointed out the level of care and precision that Kawara devoted to the details of each figure, the minute adjustments that he made. Kawara’s lettering was uniquely his own, and it changed from year to year, from these narrow letters in 1966 to wider, thinner letters in ’67, ’68, then on to chunky, fatter ones in the 1980s. He was so dedicated to the manipulation of these figures in space, making the tiniest changes over long stretches of time. You can see this particularly well in the Sunday paintings on Ramp Five, twelve paintings dating between 1966 and 1998—it was an incremental evolution.

SZ: Your parents participated in the One Million Years reading. In fact, they were the first people to read. What was their experience of this performance?

AW: My parents, Betsy and Doug Wheeler, were well-acquainted with the work after hearing me talk so much about the exhibition over the past three years, so having them come out not only to see it but also to participate in it was especially meaningful for me. Kawara’s family was really involved in his work; it was important to him that we meet everyone in his family. Involving my parents allowed me to create that connection between my work and family too.

We’ve been asking readers to share comments about their experience, and my mother wrote: “The reading was methodical and the hour went by quickly. I never had a chance to even open my water bottle, let alone take a sip. I didn’t realize that Doug had set a goal of reading 1,000 numbers in an hour. I think we ended up in the 800s somewhere. Probably the best part was being a part of the ‘action’ in the museum. School children came and went; people stopped and listened to us; people stopped and wondered what we were doing. Every time I looked up the scene around me had changed.”

Photo: David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

SZ: One thing I hadn’t realized before seeing the exhibition is the hands-on nature of Kawara’s paintings. He hand-mixed the paint colors for each Date Painting, so each one is slightly different. The telegram (I Am Still Alive) is the only medium he used that doesn’t reflect the touch of his hand. Do you think the concept of the artist’s hand was important to Kawara or had meaning to him?

AW: Though Kawara may have tried to erase his hand by making the Date Paintings so exact, I do think the concept of the artist’s hand was important to him—maybe not in the traditional way we think about it in terms of gesture and brushstrokes, but he did do everything by hand. He lettered his paintings by hand, he stamped his postcards by hand; even after the advent of computers, he still used typewriters. The making of the object and the material object, I believe, were important to him, so if not the artist’s hand, per se, perhaps it was about the artist’s participation—or presence—for Kawara.

SZ: The advent of certain technologies would have made many of Kawara’s painstaking processes much easier to complete. Can you speak a bit about Kawara’s relationship to technology—either his use or rejection of it?

AW: Kawara kept painting long after painting had been declared “dead.” And he was using telegrams at a time when they were no longer relevant; he kept sending them until it wasn’t possible. For One Million Years, there are twelve sets of ten volumes each for both Past and Future—twenty-four total sets. The last Future ones were made through 1998, and those were still laboriously cut-and-pasted and Xeroxed, which wasn’t even necessary at that point—he could have switched to a computer. At the same time, he was using a Xerox machine in the 1960s, which was then a new technology. Because it was so new, the Manhattan company where Kawara Xeroxed his work couldn’t guarantee that their ink would last beyond fifty years. So Kawara initialed the back of each page, because he knew the graphite would last. If technology failed, his mark would still remain. So maybe his relationship with technology was more conflicted than we often realize.

SZ: The On Kawara Twitterbot (@On_Kawara) has been tweeting “I AM STILL ALIVE” every day since January 2009, and has continued uninterrupted since the artist’s death. What do you think about this project?

AW: Kawara knew it existed and didn’t put a stop to it. When he died, people were confused because they thought it was Kawara himself who was still tweeting. And odd as it might sound, I think he may have been amused by this. Kawara didn’t have a social media presence. We never received an email from him. There are a lot of artists that make art based on Kawara’s or make work based on where Kawara’s work has led them—this seems similar to me.

SZ: What was the highlight of putting together this show for you?

AW: Often, in art history, I’ve felt weighed down by previous interpretations, or things artists have said about their work, so it was liberating in this case to work with an artist who was such a cipher. Kawara was a game player—he was always playing games with his work, with the world, with us. In working on this show I, too, got to play the game, to work on the riddle, to put together the pieces of the puzzle, and the possibilities for interpretation are endless. There is so much more work to be done with Kawara; though the exhibition may have come to mark the closing of Kawara’s life, it also inaugurates a new phase in the interpretation of his art, and provides the materials for people to begin that work.

Be First to Comment