Estrellita B. Brodsky is experiencing what for many art historians is a dream come true: less than three years after receiving her PhD from the Institute of Fine Arts, she has succeeded in curating an exhibition based on her dissertation research on Latin American artists working in post-war Paris. Now on view at the Grey Art Gallery on NYU’s downtown campus through March 31, 2012, her exhibition, Soto: Paris and Beyond 1950-1970, focuses on the early Paris years of the Venezuelan maestro, Jesús Rafael Soto, a key member of the post-war international avant-garde who is today best recognized for his optically-challenging, immersive, and kinetic art. Just a week after the show’s opening, Brodsky kindly agreed to meet with me at the Grey to discuss her research, curatorial experience, and of course, Soto.

Our conversation began in the center of the Grey’s main gallery, surrounded by examples of each of the various phases explored by Soto between 1950, the year of his initial departure to Paris, and 1970, a culminating moment in his career following his first Paris retrospective at the Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris and the realization of his famous Penetrables.[1] With a Cézannesque-Cubist rendering of a Venezuelan landscape behind us and an optically challenging Plexiglas piece to our right, I asked Brodsky to start at the beginning: why did she choose to study the work of Latin American artists in post-war Paris?

Explaining that her interest in Venezuelan art is rooted in her personal history (her father arrived in the country in the 1920s, and Brodsky was a first-hand witness to the country’s booming arts scene in the 1960s), she also admitted to a certain selfishness in picking her topic. “When it was suggested that I like the location where I would be spending time doing research, I of course picked Paris,” she joked. Though originally interested in artists working in the City of Lights between the wars, she took the advice of her advisor, Professor Edward Sullivan, to look into more recent generations. This prompted her to realize the relative lack of scholarship on the post-war art scene. In fact, although her research originally focused on the careers of Soto, the Argentine Julio Le Parc, and Brazilian Lygia Clark, Brodsky insists that more work needs be done in relation not only to Latin American artists from this period, but also to the post-war Parisian art scene in general, which has largely been eclipsed by that of New York in terms of scholarship.

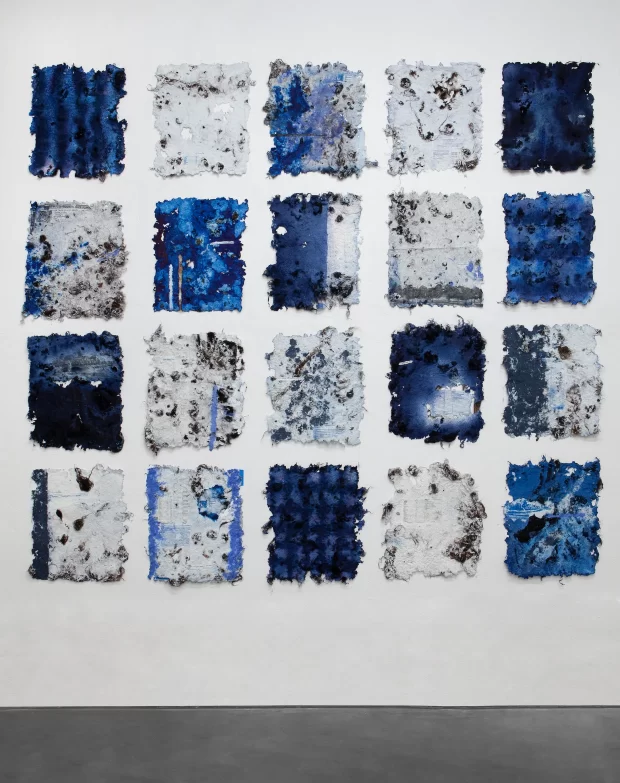

Brodsky’s description of the Paris of the 1950s and 1960s as a “hotbed of activity” is chronicled throughout the exhibition via Soto’s countless associations with other artists, who range from Marcel Duchamp and Victor Vasarely to Soto’s particularly close friend, Yves Klein. Klein’s presence is in fact particularly resonant in many of the works on display in which Soto incorporates his friend’s eponymous International Klein Blue. Supplementing such works, a video on the Düsseldorf-based collective Group Zero is on loop in the Grey’s downstairs space. Featuring a cameo by a guitar-playing Soto, this video reveals the range of the artist’s international contacts. (“I hope everyone watches the film; it’s very tongue-in-cheek, but it shows the diversity of radical approaches used by artists in Europe at the time,” Brodsky stated.) However, while Soto shared many ideas with other artists and movements, he never aligned himself with any particular group. Drawing upon my own research on Cuban artists in the 1930s, as well as the example of the Uruguayan Joaquín Torres-Garcia, who refused to side with either the abstractionists or surrealists during the 1920s, I questioned Brodsky about her thoughts on how this might relate to these artists’ identities as Latin Americans. Although wary of casting Latin Americans as exotic Others, we both considered whether a certain sense of displacement may have given such artists the beneficial freedom to move between different groups and ideas.

Continuing our discussion about notions of identity, I mentioned that I was fascinated by moments in the show when subtle references to Soto’s Venezuelan nationality were revealed in his seemingly cold, geometric abstract works. For example, I found Soto’s Ecriture series, initiated in 1962 and composed of floating rods and wires suspended before a striated plane, to be even more evocative upon learning that they were created during a period in Latin America that is often referred to as the “decade of silence” due to widespread government censorship. Comparing Soto’s position as a Venezuelan artist firmly entrenched in the international scene of Paris to that of contemporary generations of artists who question such identifying terms as “Latin American” versus “global,” I asked Brodsky if she had a sense of how Soto may have characterized himself. Although initially answering in the affirmative to both positions (“Soto was a Venezuelan artist who wanted to be considered an international artist—which he was”), Brodsky then referred to a quote by Soto’s compatriot, the artist Alejandro Otero. Responding to the Argentine art historian, Marta Traba, who famously evaluated the art of Latin American nations based on their perceived receptiveness to or defensiveness against Western artistic practices, in 1963 Otero pointed out the inherent racism of her theory, noting how not all Venezuelans are the same: “There are many Venezuelas that Marta Traba cannot distinguish between, and one of them is precisely the one that Soto represents in committing himself to a search devoid of any localism.” Thinking back to our original question about artists’ associations, Brodsky mused, “Ultimately, I think artists want to be artists. I don’t believe that national boundaries are what define art.”

![Petite écriture noire [Small Black Writing], 1968](http://ifacontemporary.files.wordpress.com/2012/01/50-petite-ecriture-noire2.jpg)

Moving away from such lofty discussions toward more practical matters, I questioned Brodsky about how the idea for a Soto show at the Grey Art Gallery had first come about. Had she anticipated curating a show while writing her dissertation? Lynn Gumpert, director of the Grey, had long been interested in a show focused on the Venezuelan artist’s career. While acclaimed Soto expert Ariel Jiménez had originally been involved, the project eventually passed into Brodsky’s hands as a result of her dissertation work. Tailoring the show to her own expertise on Soto’s lesser-known years in Paris, Brodsky acknowledged that she originally had conceived of the show as a “transnational dialogue.” Featuring art by both Soto and his “artist-friends,” Brodsky had wanted to exhibit works from Soto’s private collection, the core of the Colección Fundación Museo de Arte Moderno Jesús Soto in Ciudad Bolívar, Venezuela. However, she realized that while Soto’s name is widely recognized in both Venezuela and Paris it remains little known in the United States; accordingly, she felt that he “deserved” to have a show dedicated to his production alone.

Acknowledging that her dissertation research must have prepared her well for curating the exhibition, I asked if she had been surprised by anything that she learned during the show’s production. With an enthusiastic “Yes,” she related how she had been particularly struck by the material presence of the works. Revealing her admiration for Soto’s art, she spoke passionately about “the physical presence of many of the works. Even some of the smallest ones seem full of power.” Bringing me towards Sin titulo (Composicion dinamica) [Untitled (Dynamic Composition)] of 1950-51, Brodsky explained how, based on catalogue illustrations, she had not realized the three-dimensional aspect of the panels until she saw the physical object. Then, moving into the area of the exhibition dedicated to Soto’s serial compositions, she pointed to the diversity of materials used in various works, calling my attention to the sequins which make up the black dots in Points blancs sur points noirs [White Points over Black Points] (1954), as well as the fact that in Sans titre (Etude pour une serie) [Untitled (Study for a Series)] (1952-53), some of the dots are painted on, while others are glued to the surface. “I am looking forward to the IFA Conservation Center professors and students coming to evaluate these works,” she expressed.

From the curatorial perspective, Mural (1961), a monumental work that takes center stage at the Grey, was one of the most challenging pieces to install. Measuring almost 10 x 16 feet and weighing over a ton, it required the construction of a special crate and accompaniment by a courier from Venezuela to transport and install the work. Soto made the mural during a trip home to Caracas for a solo exhibition at the Museo de Bellas Artes, following an invitation by the politically dissident group El Techo de la Ballena to create a work in one day. Mural is divided into two sections. On the left, debris ranging from pipes and wire to hair and even a broom are embedded in tar against the mural’s black background. On the right, similar pieces of wire and metallic plates are soldered onto a raised structure that hovers over Soto’s characteristic black-and-white striated background. Representing a confrontation between a Nouveaux Réalistes style work and Soto’s earlier aesthetic, the mural has only been exhibited outside of Venezuela once: at Soto’s 1997 retrospective at the Galerie Nationale du Jeu de Paume.

Asked whether she had any advice for IFA students who might one day find themselves curating an exhibition with works coming from areas of the world that present challenges similar to those posed by Venezuela, Brodsky was adamant about the importance of communicating one’s passion in the field: “Ideally, I would also recommend doing primary research and personally meeting the artists and curators involved. It’s very easy for someone to say no to you on paper. But once you meet them and form a relationship it is much easier to have their support in realizing a mutual goal. To make the exhibition possible, I traveled to Venezuela where I met with collectors and institutions. Once they were assured of my commitment to the artist, I found that no one went back on what they had promised.”

Speaking with Brodsky amidst Soto’s artworks, her commitment to furthering the understanding of his and other Latin American artists’ careers is clear. Before we parted, I asked her about a quote by Soto that she included in her exhibition catalogue. The quote reads: “I consider Art with a capital A (and I use the term unashamedly) not as a way of speculating about beauty, but above all as a form of knowledge, a kind of sensitive thought embedded in the general context of a culture that it directly helps to create.”[2] As the presenters of artworks, curators and art historians also help to create a certain form of knowledge, I suggested: What do you hope was your contribution in curating Soto: Paris and Beyond? Thinking for a moment, Brodsky then responded that what she wanted was for viewers to come to the show without pre-conceived ideas about Soto or his art. “I want them to come in and truly engage with the art—which, after all, is what I believe forms the basis of Soto’s own artistic practice.”

On February 3, 2012, Brodsky will be featured in conversation with IFA professor Edward Sullivan at an NYU event hosted at La Maison Française (16 Washington Mews) called Soto and Latin American Artists in Paris. Respondents will include Temkin and IFA students Sean Nesselrode, Rachel Kim, and Amelia Langer.

1. Composed of colored, tubular rubber strands suspended from above, Soto’s Penetrable series represent the culmination of his career, allowing viewers to fully immerse themselves in his art.

2. Grey Art Gallery, Soto: Paris and Beyond 1950-1970, Ed. Estrellita Brodsky, (New York, Grey Art Gallery, 2012). [Exhibition catalogue]

Be First to Comment