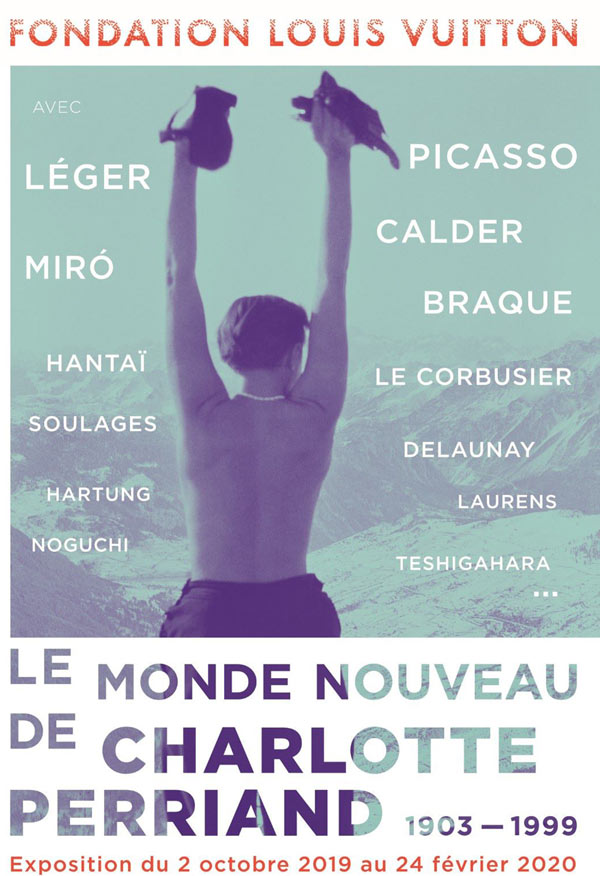

Pictured on street corners and plastered throughout the metro system, an eye-catching image announcing the Fondation Louis Vuitton’s current exhibition Charlotte Perriand: Inventing a New World has bombarded Parisians for weeks. In the advertisement, a photograph shows the architect-designer Perriand (1903–1999) silhouetted against her native French Alps, sparsely outfitted in only pants and a pearl necklace, thrusting a pair of mittens skyward. Occupying the negative space around her figure are the names of notable twentieth-century male artists. Yet whereas some of these men were instrumental in Perriand’s personal and professional life (Fernand Léger, Le Corbusier), a number had little or nothing to do with her career (Pablo Picasso, Alexander Calder). At the same time, more significant characters, such as Pierre Jeanneret and Jean Prouvé, are absent from the poster and receive only passing reference in the exhibition.

This positioning of Perriand as a fiercely independent woman operating in the orbit of powerful men is both the show’s central organizing strategy and its major flaw. In so doing, the curators purposefully obscure Perriand’s commitment to artistic collaboration while the commercial undercurrent suggests that in order to “sell” Perriand to a naïve public she must be introduced in relation to better-known men. As a result, the overwhelming sensation one has throughout the exhibition is not so much that it is a retrospective of Perriand’s work, but an exhibition about Perriand in the company of male artists and designers. And yet, despite this emphasis that Perriand existed among said men, there is the simultaneous claim that she did so while acting alone. This erasure of her partnerships seems odd given the curatorial focus throughout the show on her belief—shared with many others during the postwar period—in a synthesis of the arts, uniting all creative fields and actors to “invent a new world,” as the exhibition’s title suggests.

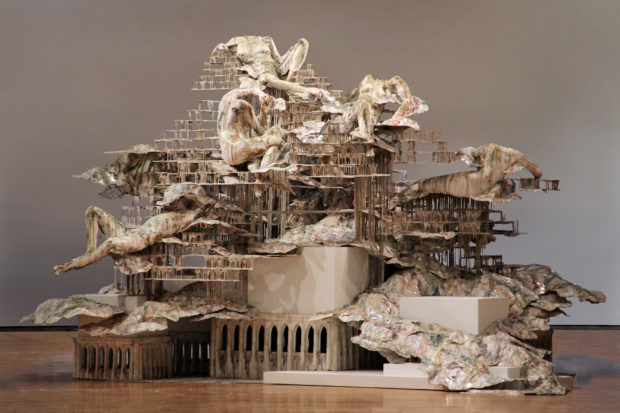

What is significant, however, is that the exhibition marks the second occasion the Fondation Louis Vuitton has given over the entirety of its sumptuous spaces and budget to a single figure (the only other time being the inaugural Frank Gehry exhibition in 2015). Spread across four floors, the curators deftly demonstrate the diversity of Perriand’s abilities and aesthetics, juxtaposing the shiny Machine Age classicism of the Salon d’Automne pavilion (1929) with the vernacular primitivism of the House for a Young Man at the Universal Exposition in Brussels only a few years later (1935). From these early experiments to later travels in Brazil and Japan, Perriand’s unwavering commitment to combining functionalism with truth to materials is highlighted. Perriand perhaps achieved this most spectacularly when she delicately transformed local materials to test variety within her universal designs, as with the Chaise Longue LC4, which she produced in chromium, cowhide, and even bamboo.

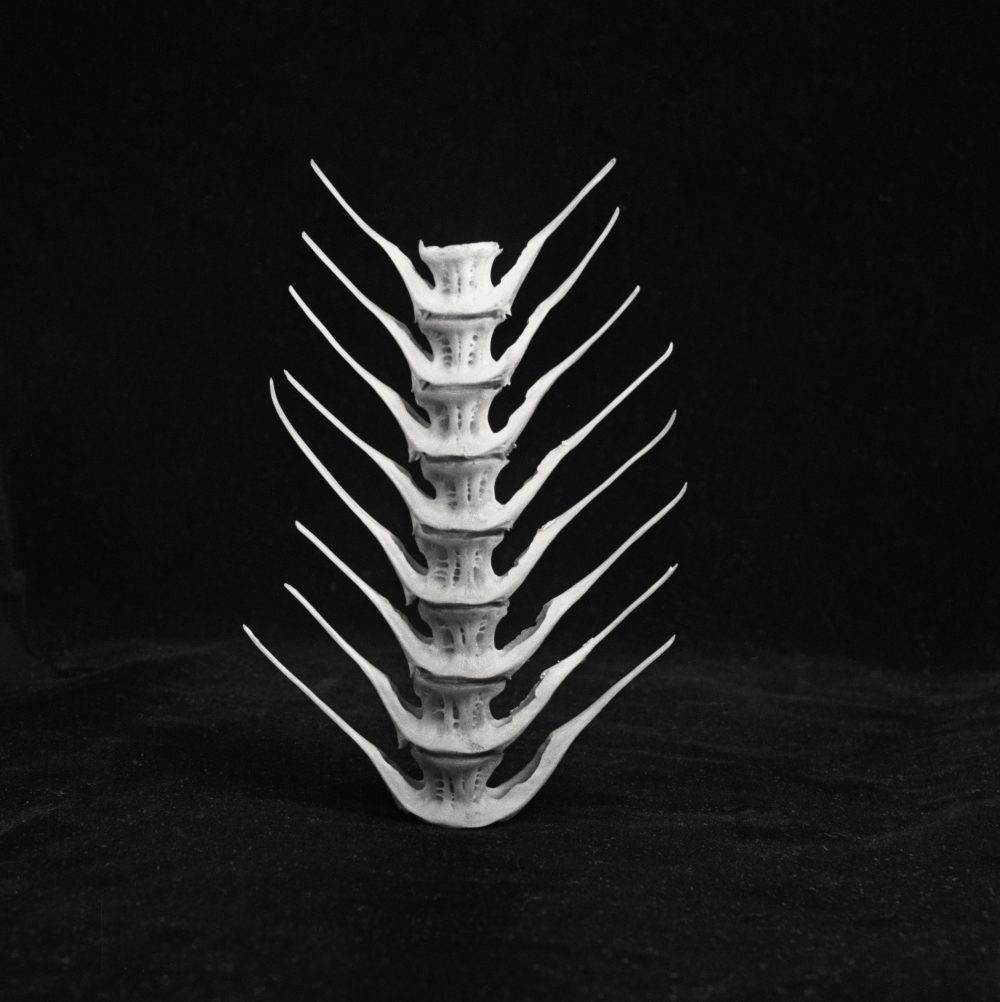

The sheer breadth of Perriand’s talents are also on display, from industrial design and architecture to collage and drawing. Photographs in which seashells and snowballs become intriguing subjects in their own right are captivating studies in organic forms. Yet in these cases, Perriand’s work should have been able to sing for itself or in concert with her own explorations of similar themes, rather than be awkwardly encumbered by the work of her male contemporaries. Unfortunately, in these pairings, the emphasis on nature and its interrelationships falls painfully flat, as in a gallery where the uniting theme seems simply to be that of wood. Here, a highly abstracted woodcutter by Léger stands opposite Perriand’s oak Ventaglio Table (1972), while a roughly-hewn tree trunk sculpture from her studio is paired with a Le Corbusier painting, the title of which nominally mentions trees.

These forced comparisons are perhaps a result of the fact that exhibiting architecture presents particular challenges; most visitors shy away from technical documents, finding plans, elevations, and sections too difficult to read or comprehend. In this exhibition, however, the FLV, with help from Italian furniture giant Cassina, has facilitated multiple in-the-round experiences for viewers to compare with archival footage. For example, framed studies of the Boomerang Desk (1938) for leftist journal editor Jean-Richard Bloch are complemented by contemporary replicas, as well as photographs of the original desk in use, ranging from staged magazine spreads to project a highly crafted image of Bloch to more candid snapshots documenting the frenzied disarray of the editorial process. Shifting between these representations, one comes to understand Perriand’s attentive study of the user’s needs (in this case, meeting with editorial team members while avoiding a sense of hierarchy, organizing layouts, and courting investors), combining worker efficiency with her signature lyricism and bending her earlier affection for the right angle to a new asymmetrical free form.

Less successfully, the exhibition also seems to capitalize on the “Me Too” moment and the current tenor of feminism in France. In the museum gift shop, visitors can purchase a white T-shirt with the seductive promotional photo of Perriand printed on the front and exhibition details on the back, while accompanying public programming sought to address the age-old debate of how to celebrate—and recuperate—female artists: by retroactively inserting them into the canon or establishing new and separate art histories? In a room dedicated to her postwar period in France, we learn that Perriand was named “Minister of Reconstruction” in a fictive “Ministry of Women” organized by Elle magazine in 1950. Yet we should remember that Perriand’s compact kitchen design for the Unité d’Habitation in Marseille (1952) and minimalist bedroom equipment used in student housing at the Cité Universitaire in Paris (1953) arguably had greater impact on public housing and dormitory design than the combined efforts of her male peers officially employed by the MRU (ministère de la Reconstruction et de l’Urbanisme). The problem, we are told, is merely a case of misattribution: men are given architecture with a capital A, while women are assigned interior furnishing. Yet if Le Corbusier famously quipped to a young Perriand when she first inquired about employment that “We don’t embroider cushions here,” by the end of the exhibition the tables have turned, wherein Le Corbusier and Léger’s late forays into that most “feminine” field of art—textile design—become décor for Perriand’s architecture as she moved evermore toward the creation of spaces rather than objects to inhabit them.

These small points aside, no other female artist received the same level of critical attention and capital support in 2019, making the (re)introduction of Perriand to a wider public not without merit. With some of the designs dating to over a century ago, many will likely be struck by the freshness and immediacy with which it all still feels so resolutely modern—even contemporary. And in this sense, the previously unknown Perriand suddenly seems familiar. Like many other “forgotten” and overlooked women artists and architects, her imprint has been with us all along; more sleek and subtle than bold and boisterous, but so fitting to the point of being unnoticed, as with her near-ubiquitous stools and chairs. In the end, Perriand certainly did help invent the “new world” we now inhabit—she just didn’t insist on getting singular credit for doing so.

Be First to Comment