On February 29, 2012, Professor Jean-Louis Cohen gave a public talk on his new book, Architecture in Uniform: Designing and Building for WWII, at the Mid-Manhattan branch of the New York Public Library.

Cohen began research for Architecture in Uniform—a project that would be some fifteen years in the making—as a way to pay some long overdue attention to architectural production during World War II. In the existing scholarship, most of the focus is placed on the avant-garde 1920s, groundbreaking interwar building, and post-WWII reconstruction. The years 1937 to 1945–during which time the preparation, mobilization, destruction, and reconstruction associated with WWII took place–are noticeably absent from many survey texts of modern architectural history. Cohen’s aim was to investigate and ultimately to close this curious gap in the scholarship, which the author indubitably does.

Cohen opened his NYPL lecture with some biographical information, which helped the audience understand his personal motivations and investment in the project. His parents were both active in the French Resistance, and in 1943 his mother was interned at Auschwitz for almost a year. With such an intense familial connection to the period, Cohen wanted to know what architects were doing at this time—a historical moment that has been thoroughly scrutinized by practically every other discipline. The book, an attempt to map both Axis and Allied architects during WWII, delves into the wartime activities of Hitler’s Albert Speer, Italian rationalist Giuseppe Pagano, and Charles and Ray Eames, among other figures. What Cohen found, and what Architecture in Uniform clearly shows, is that thousands of architects were at work. Their intensity and engagement during the war led to the heightened expertise in building, organization, and observation that would be duly implemented in the postwar years.

As many have noted, World War II was an air war and, moreover, a war fought against cities. Thus the concept of the front was subverted, making this conflict markedly different from World War I. While some architects were on the front lines, most did not serve in the military in the traditional sense. Some participated as building managers and designers. Many young German architects, not affiliated with the Nazis, were beginning their careers during the war. One of the new “fronts” of WWII was the factory. With men needed on the fighting lines, many women took over critical positions as factory workers. Advancements such as fluorescent lighting, air conditioning, and lightweight building led to the “big box” aesthetic that we are familiar with today. One of the American examples Cohen cited in his talk was the Chrysler Tank Arsenal by Albert Kahn Associates in Warren Township, Michigan. The 1,300-foot-long and 500-foot-wide “glazed envelope” arsenal housed long assembly lines, with its total wartime work force numbering five thousand. These workers would end up assembling 25,000 tanks for the war effort.

Los Angeles played a particularly interesting role in wartime architectural production in America. During this period, the city became an aviation boomtown, with some 250,000 industry workers concentrated there. During the 1930s, the city engaged in a few Garden City-type housing projects, including Richard Neutra’s Channel Heights in San Pedro, California, a federally funded project for shipyard defense workers near the L.A. harbor. The executed plan consisted of 222 residences, which would provide housing for 600 families at an average cost of $2600 per unit built. The discourse on housing was lively elsewhere in the country as well, aided in part by MoMA’s wartime housing exhibition in New York City, which was on view from 1943 to 1944.

The topic within Cohen’s discussion that I found most fascinating was industrial camouflage. A defense strategy inspired by air combats, but dating back to WWI, industrial camouflage engaged military and city planners alike in creative and often elaborate design solutions to blur vision and conceal entire cities from aerial bombers. Artists, architects, and engineers worked together to create a comprehensive program that benefitted from each of its contributors’ areas of expertise. Former Bauhaus Meister Laszlo Moholy-Nagy and artist György Kepes applied Bauhaus theories of visual language and Gestalt psychology to develop a camouflage strategy at the scale of an entire city. In Los Angeles, the studios of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Disney, Fox, Paramount, and Universal all brainstormed projects for military bases.

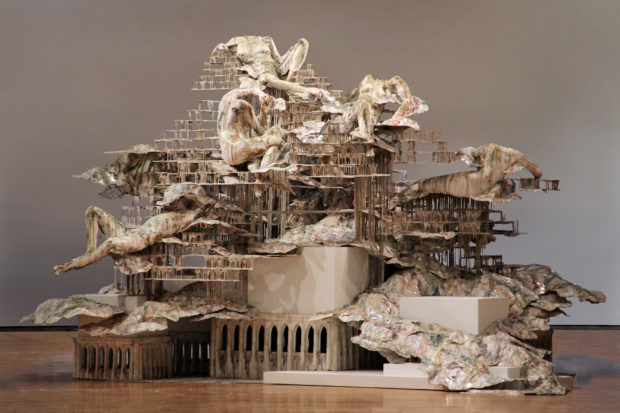

Right: Data on Bombardment, from Konrad F. Wittmann, Industrial Camouflage Manual, 1942. Courtesy of the CCA.

As Cohen stated in his closing remarks, architecture during WWII was, in many ways, about defining a future for those engaged. Architects and urban planners enabled the notion of these futures not only by working to preserve the present, but also by envisioning and realizing them from inside the pressure cooker of war.

Be First to Comment