A sidelong glance reveals as much as a direct gaze—which Hans Holbein the Younger humorously demonstrated in The Ambassadors (1533) by depicting a skull at the bottom of the painting that can only be deciphered at an oblique angle. Aptly titled A Sidelong Glance after the eponymously titled essay by art historian Krista Thompson, John Edmonds’s first solo museum exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum takes as its subject the revelatory power of the side eye. Instead of signifying disapproval, staring sideways here represents the dynamics of looking and being looked at. Through different implications of the side eye, Edmonds’s portraits and still lifes of Central and West African objects offer a trenchant reflection on questions of identity, race, sexuality, and museum politics.

The exhibition, however, starts with an outlier. Conceived a year after Edmonds received his MFA from Yale University and moved to Crown Heights, Brooklyn, American Gods (2017) is a group portrait of three young Black men who wear red, black, and green du-rags—collectively comprising the colors of the Pan-African flag. While, unlike other works, this photograph of six piercing eyes does not feature any African art objects, it reminds us where this emerging artist started and how far he has come. In his formative years, Edmonds set out to explore one crucial subject in his oeuvre, i.e., the intimate connection between African American individuals and the objects often associated with their identity through the lens of a large-format camera. Just two years later, his work would be included in the Whitney Biennial, Company Gallery would organize his first solo exhibition, and the Brooklyn Museum would grant him the UOVO Prize—an award which led to the current exhibition. American Gods thus serves as a prelude to the three bodies of work in this show: portraits and still lifes of African objects from a Brooklyn family, the artist’s collection, and the Brooklyn Museum’s collection that was donated by Ralph Ellison.

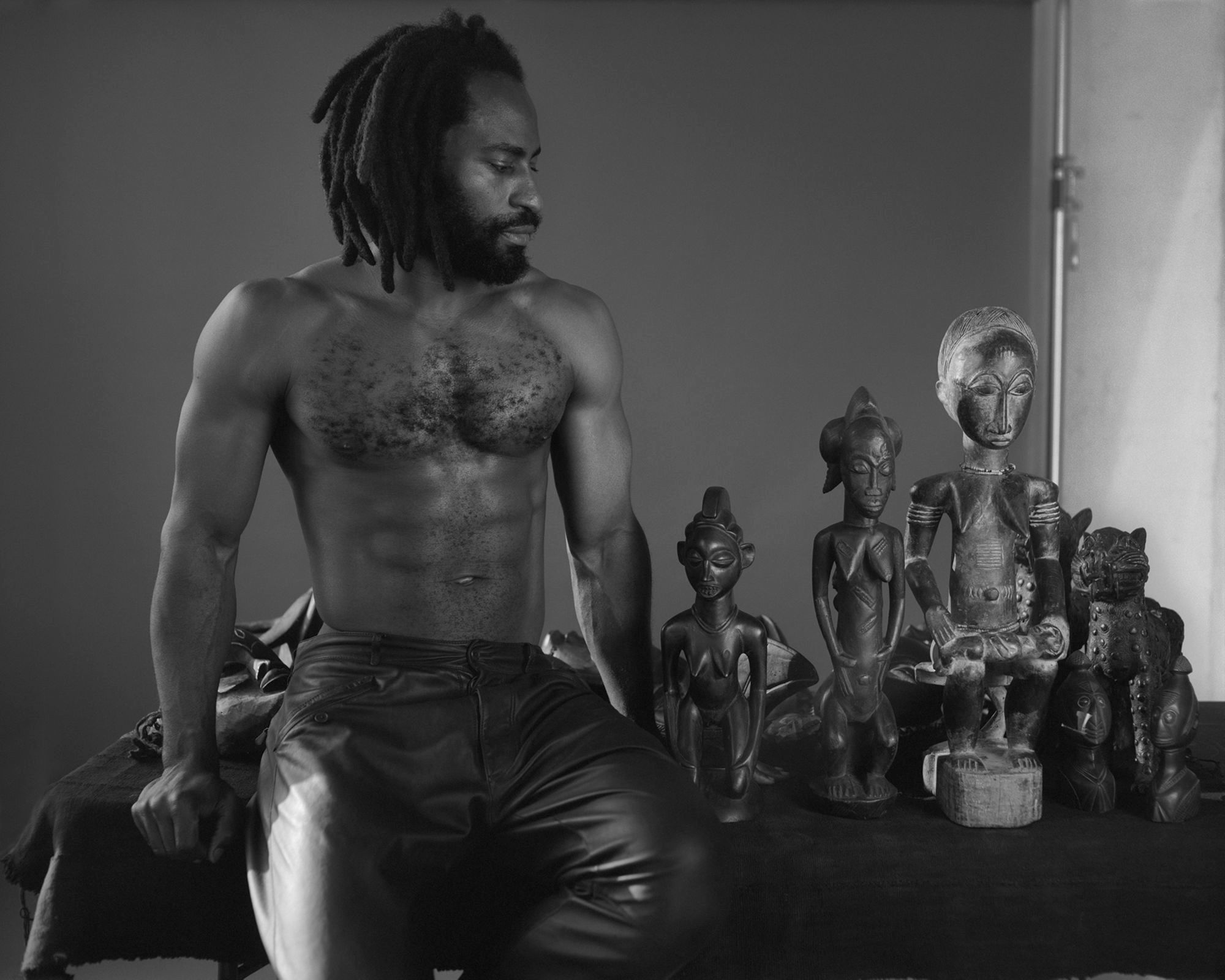

Anatolli & Collection (2019) is one of the few portraits on view in which the subject literally gives the side eye. On the one hand, the man’s oblique and downward gaze evinces an agency and presence that distinguish him from the inanimate African objects. This pensive figure is possibly an existential projection of Edmonds, who has spoken of this work as a visual investigation of his “own positionality as an African-American artist looking at such layered material of the diaspora.”[1] On the other hand, when the artist places the half-naked, muscular and hirsute man in close proximity to the ensemble of African sculptures that he collected, the possessive power of the camera turns this eroticized body into one of the works of art—a commodity for acquisition and display. Such juxtaposition does not only suggest an analogy commenting on the objectification of Black men and African sculpture, but it also equates the material desire of collecting to the fleshly desire of sexuality. Indeed, the act of collecting art can be as thrilling, and at times as scandalous, as sex.

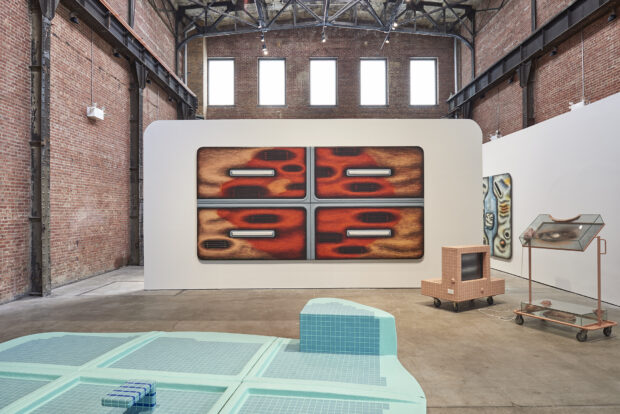

![Brooklyn Museum, Installation view, John Edmonds: A Sidelong Glance, October 23, 2020 through August 8, 2021. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado, Brooklyn Museum). From left: Collapse (2019), American Gods (2017), and Tete de Femme [Portrait of Ladin] (2018).](http://ifacontemporary.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/DIG_E_2020_John_Edmonds_A_Sidelong_Glance_04_PS11-General-Use-JPEG-620x414.jpg)

In her essay, Krista Thompson employs the sidelong glance metaphorically to indicate a suspicion towards Western modes of representation, which neglect the fact that “African diaspora art history is part of and offers invaluable perspectives on … Western art history.”[2] With a similar skepticism, Edmonds engages with canonical Western art historical tropes that problematically depict blackness as tangential and ancillary. Female Nude (2019) recalls the reclining pose of Manet’s Olympia (1963), whose titular figure is accompanied by the often overlooked Black female servant; Tête de Femme [Portrait of Ladin] (2018) references Man Ray’s surrealist photograph Noire et blanche (1926), which compares an Ivorian Baule mask, devoid of its ceremonial purpose, to the ideal beauty of the artist’s muse, Kiki de Montparnasse; Bull Mask (From the Ivory Coast) (2019) alludes to Picasso’s bull ceramics and, by extension, the artist’s development of cubism, which relied upon the exoticization of African masks. In these seemingly anodyne appropriations rendered in elegant compositions, Edmonds subversively restages art history as if it is a play, but this time the leading actors are Black and often queer.

Directing one’s gaze to the side does not only retrieve unheralded subjects, it also affords a formal reorientation, exposing what was previously left out of the picture’s frame. Edmonds’ other works, such as Alpha (2018) and Still Life II (2018), evoke Walker Evans’s photo documentation of objects exhibited in the groundbreaking exhibition African Negro Art at the Museum of Modern Art in 1935. However, while museum objects are often photographed against a white or neutral backdrop, Edmonds uses gold fabric hung on the wall or placed on a table. Our habitual attention to the object at the center of each image is thus directed to the shimmering, metallic periphery. In this way, Edmonds initiates a critique of institutional practices, encouraging viewers to take note of the context surrounding museum collections, which often falsely purport to be historically objective and politically neutral.

Ultimately, Edmonds’ work amounts to far more than a sidelong glance. Its humor solicits a knowing wink, its subversive gestures more closely approximate the antagonism of eye-rolling, and the conceptual engagement it elicits is better embodied by a furrowed brow. No matter the ocular movement, it is certain that all eyes will be on this rising queer artist in the years ahead.[3]

[1] John Edmonds, quoted in “Press Release: UOVO + Brooklyn Museum Unveil Design,” UOVO, November 13, 2019.

[2] Krista Thompson, “A Sidelong Glance: The Practice of African Diaspora Art History in the United States,” Art Journal 70, no.3 (Fall 2011): 29.

[3] This exhibition review was written for Prof. Linda Wolk-Simon’s course titled Identity Politics in Late Renaissance Florence: Portraits, Power and the Medici at the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. I owe tremendous gratitude to Prof. Wolk-Simon for her inspiring lectures, constructive comments and generous encouragement.

Be First to Comment