In early November, 2022, participants arrived at Korean Art Week in Boston and Hanover, MA, to attend a conference organized by the Korea Foundation, Dartmouth College, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Korea, and the Korea Institute at Harvard University. For most participants, this was the first-time they had ever visited Hanover and the atmosphere was filled with both anxiety and excitement as we prepared to learn more about trends in contemporary Korean art in exhibitions across the U.S. as well as Korea.

In the first event, renowned contemporary Korean artist Park Dae Sung gave a lecture on his life and artworks. He stressed the importance of learning from nature and the danger of being too materialistic in modern society. His paintings showed a landscape of his mind as he illustrated imagined ideals through direct observation of the rural areas in Korea. I first came to know Park’s painting through an Instagram post from RM, a member of the musical group BTS, who has become a prolific emerging collector in the Korean art world. He has not only participated in major art exhibitions and art fairs as a collector, but has also invested a substantial amount of money and time in promoting Korean artists using his platform. The K-pop idol’s influential social media has succeeded in drawing international attention towards Park Dae Sung, and although he has received criticism for this, I do not agree that it is an abuse of RM’s power to use his platform to promote the work of an artist who deserves such recognition and has indeed already been receiving it from other institutions as well. This endorsement also guarantees an effective outcome in terms of Park’s market value, helping support the artist’s projects and ability to continue making work.

The first session on the second day of the conference focused on critical practices and contemporaneity in Korean art. Professor Park Soyang of OCAD University and Professor Shin Chunghoon of Seoul National University gave an extensive lecture on Minjung art, which is literally translated as “people’s art.” They focused on defining the boundaries of Minjung art, a style that originated in 1980s Korea and emphasizes the realities of the working class. Professor Kim Mina focused on contemporary styles of Korean art, prompting me to consider what sets Korean art apart from Japanese and Chinese art both historically and visually.

Korean art cannot be explained without the dynamics of Korean history. The Korean War in the 1950s and the emergence of military dictatorships in the 1980s greatly impacted the creative culture of the country. For example, Park Dae Sung lost his parents as well as his arm during the Korean war and thus, he sought solace in painting and calligraphy. After the war, the Korean art world became a battleground between capitalist and socialist styles as artists in South Korea sought their own unique voices among the influx of trends from Japan and America. Although some scholars doubt the necessity of uncovering a Korean aesthetic within this work, others believe that it contains an essential Koreanness that continues to evolve and deserves to be explored.

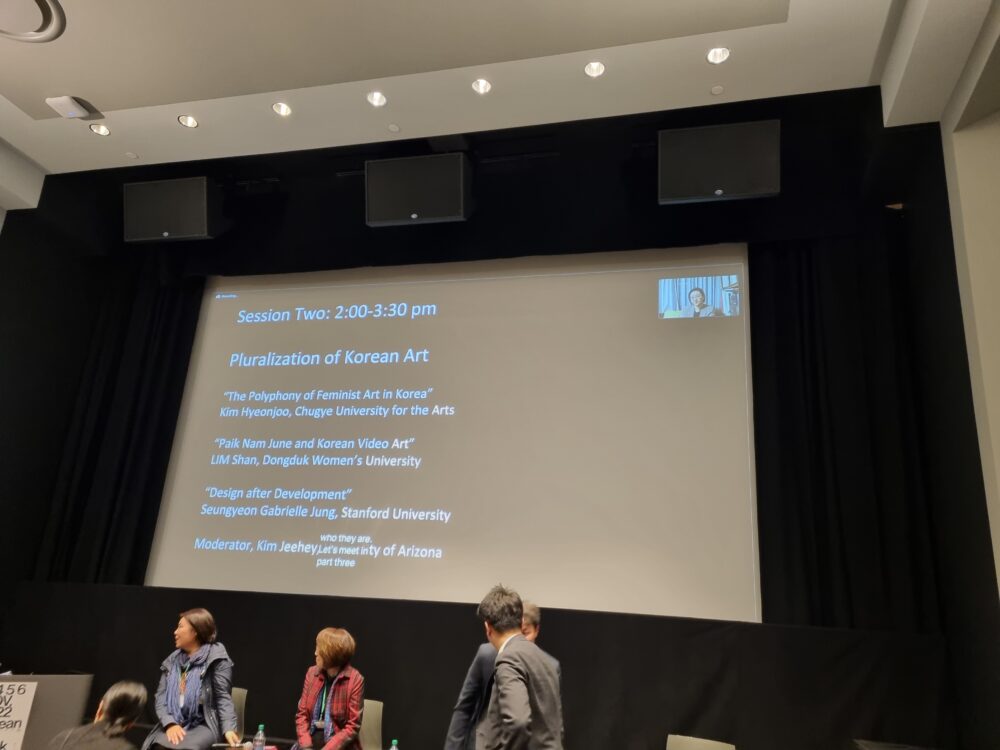

In the second session, Professor Kim Hyeonjoo of Chugye University for the Arts discussed the intersection of feminist thought and art in Korea, whereas Professor Lim Shan of Dongduk Women’s University talked about Korean video art with a special focus on Paik Nam June. Next, Professor Seungyeon Gabrielle Jung of the University of California, Irvine offered a meaningful lecture on modern design in South Korea. While it was thought-provoking to see how feminist art, video art, and design have helped shape discourse surrounding contemporary Korean art, the history of decorative arts in Korea could have been further examined. Many of us in the audience were left to wonder how material culture studies are currently developing, especially as is relates to, and overlaps with, the history of feminism in Korea. Addressing the subjects of contemporary ceramics, modern hanbok (a traditional Korean garment), furniture, and street fashion would have enriched this session.

The third day of the conference was the highlight of the week. A bus arrived in Hanover to take us to Boston, where we first met with the Harvard Art Museums’ chief curator, Soyoung Lee. Harvard Art Museum has one of the most notable Korean art collections among universities in the U.S. as their Korean collections range from ancient to modern and contemporary artworks, including Kim Whanki’s paintings. After looking at his piece Flying Bird and Blue Moon (1958), I engaged in conversation with a fellow conference member whose research focuses on the artworks of Kim Hyang-an, Kim Whanki’s wife. As Kim Hyang-an’s artworks are far less studied than Kim Whanki’s, I thought more research should be proposed on the development of her life and work. There is an obvious gap in research between male and female artists in Korean history that desperately needs to be improved and made more accessible.

On the final day of the conference, we headed to the Museum of Fine Art, Boston. The Korean art gallery at the MFA shows a wide range of objects such as celadons, Buddhist reliquaries, and contemporary ceramics. Among them, my eye caught Yeesookyung’s Translated Vase (2011), which is made of shards of porcelain and celadon pots repaired by gold and lacquer. From celadon vases to Moon jars, Korea was central to the East Asian ceramic cultures during the Goryeo and Joseon Dynasties, and Korean artisans frequently destroyed any flawed, low-quality works to produce only the best product. Yeesookyung’s inspiration stems from this practice as she collects discarded fragments of ceramics by contemporary ceramic masters. Her works show that shattered or broken pieces of ceramic can also contribute to the perfect harmony of a piece.

2022 Korean Art Week succeeded in gathering both young scholars and established professionals to draw their attention to the contemporary Korean art scene. Through this event, I not only learned about trends in Korean art research, but also felt compelled to promote authentic Korean art in my own research. Although hosting this event in the U.S. left a positive impact on raising awareness of Korean art among Euro-American-focused scholars, I hope these kinds of events can also take place in Korea, inviting overseas artists and art historians alike to see and experience Korean art in its home. Additionally, I hope more institutional support such as funding and research opportunities can be available to emerging scholars in the field of Korean art. Compared to Chinese and Japanese art, there are less opportunities for people who major in Korean art because U.S. institutions and university faculty do not tend to prioritize or specialize this work or culture. Even with a PhD in Korean art, becoming a professor or a curator is especially challenging as jobs are few and far between. 2022 Korean Art Week was especially meaningful in initiating this kind of conversation among scholars and raising awareness of the limited opportunities that are available for academics and curators in this field. The event should have been broadcast online to become more accessible to a larger audience; this choice was disappointing because the content was and is so important. Regardless of nationality, gender, or academic background, I hope to see more participants in future conferences share opinions and discuss where Korean art may go in the future.

Kye Jin Lee is from Seoul, South Korea and is pursuing a Master’s degree at the Institute of Fine Arts to study Sino-Korean and Japanese-Korean artistic exchange. Her research interests include analyzing art objects like calligraphy, ink and water paintings, literati paintings in East Asia.

Be First to Comment