Adding to the ever-increasing influx of (add preferred noun here: airtime, hype, prestige, simple volume of written or spoken words) about Koons’s work in the wake of the Whitney’s current retrospective, the joint IFA-Whitney symposium, The Koons Effect was a game participant. Unlike much of the other dialogue around the show, however, The Koons Effect aimed for tough methodological questions from the start; indeed the symposium could be said to have centered on the question of whether Koons’s work proves itself beyond the pale of established historical interpretative frameworks and vocabularies, warranting something “new.” Two points were immediately clear: facile and default recourse to models (like the commodity fetish) or to figures (like Duchamp and Warhol) bear little fruit in the collective effort to advance the discourse on Koons, and the lighter the reliance on the artist’s own manicured explanations and language of self-presentation, the deeper the insight.

Rather than synopsizing the conference here, however, what follows are abbreviated summaries of four of Friday’s eight presentations, in part to signal their diversity (I consider only part two of the event, the September 12 proceedings, which were fully recorded and are available online). The challenge of precisely summarizing any individual talk points not only to the complexity of the ideas grappled with and the lines of inquiry opened up, but—and maybe more importantly—the supremely unresolved state of current thinking on the artist. Whitney curator Scott Rothkopf’s show is revelatory for bringing the full trajectory of Koons’s production into view, enabling—unbelievably—for the first time what one hopes will be a spate of ambitious art historical work based on direct experience and study of the objects.

By way of the ever-articulate Stephen Colbert (an apt choice, considering his status as pop culture icon and, importantly, self-fashioned political pundit) the New Museum’s Johanna Burton sought to parse tensions in the experience of Koons’s work, starting with the artist’s apparently simultaneous occupation of two opposing positions (the artist as protector of culture, on the one hand, and a new, more multivalent role on the other) and following with the contradictory modes of viewership his work impels in its viewers. For her, Koons’s objects are slow and static at the same time that they are “affectively, atmospherically, and connotationally incredibly fast.” Burton described the styles of beholding she witnessed unfolding in the Whitney retrospective: “A strange tempo fills the galleries as viewers work to keep themselves in front of objects that say, ‘stop and look at me very carefully because I am made by a real artist so you should care about my construction, my materials, and my objecthood;’ and also, ‘you know what I am, without even looking at me! I am simply affirming myself, and you, by being here. A glance will do.’” The acceleration Burton observes vis-à-vis Koons’s objects rhymes with the dynamic that is part and parcel of taste, and points to a question that loomed throughout the conference: how—and whether—to look at anything in the twenty-first century.

Artist Josiah McElheny, too, stressed the contradictory nature of much of Koons’s work and reception, only this time by closely examining the artist’s techniques and resulting surfaces. Offering the provocative thought that one of Koons’s objects could conceivably represent the highest tally in collective hours of hand labor in the twenty-first century outside the field of architecture, McElheny noted that Koons does not readily admit to the collaborative nature of his artworks despite their contingency upon such partnerships. Focusing on Koons’s Equilibrium and Statuary series, McElheny rightly articulated the tension between the recent discussion of Koons’s oeuvre as easy breezy fun and Lifeboat’s (1985) menacing reality. Materially, too, a tension is captured in the process of production—getting those puckers not only to look right but to feel right—from the bronze inflatables to the stainless steel bunny and right up to the most recent monumental balloon sculptures of Antiquity. Koons works against the properties of his materials (McElheny reads stubbornness here, and even rage) by casting the ephemeral inflatable into immortality, forcing molten metals into crevices they don’t want to enter, and polishing these pieces to such a degree that, for example, the placement of the sprue becomes all but impossible to imagine. Ultimately, Lifeboat, like Aqualung and Snorkel (Shotgun), is an object of deception, a trick not only of the mind (life raft not as saving grace but element of suicide), or the eye (bronze, not vinyl), but also of technique (a seeming copy, theoretically simple, but an incredible physical and technical challenge). Koons’s objects seem to cancel themselves at every turn.

Artforum editor Michelle Kuo delved further into this dichotomy between close-looking and speed-reading, as it were, by revealing that the extremely precise specifications of Koons’s high-tech, extraordinarily sophisticated, custom modes of production often exceed even those of the aerospace and transportation industries. Demonstrating Koons’s explosion of perceived norms and procedures in the realm of technology and production finds resonance with one of the symposium’s undercurrents: that by sitting so uneasily alongside extant interpretative strategies and vocabularies, Koons perhaps explodes these, too. In works such as Balloon Venus (Orange) (2008–12), Koons employs a CT scanner which (unlike a flatbed scanner that uses light rays that can only see the outside of an object) uses X-rays that can penetrate the inside of an object to scan a balloon figurine of the Venus of Willendorf. The messy digital data resulting from the CT scan is then “cleaned up” by a bevy of studio assistants and subsequently used to fabricate a blown-up, mirror-finish sculpture. Kuo elucidated how even more recently, Koons’s collaboration with such partners as MIT’s Center for Bits and Atoms, with its stated remit of “digitizing materials,” permits Koons to fabricate objects to a previously-unrealized degree of specification; the artist is currently investigating the use of voxels, or volumetric pixels, which produce three dimensional renderings that could then, conceivably, be transferred back into physical matter. Kuo notes that mimesis between works in a series may fall away as connections between artworks take a conceptual turn, related more by the algorithms that produce them than the physical likenesses of the products themselves (and displacing, for example, some of the discipline’s favored frameworks of index, aura, and industrial replication).

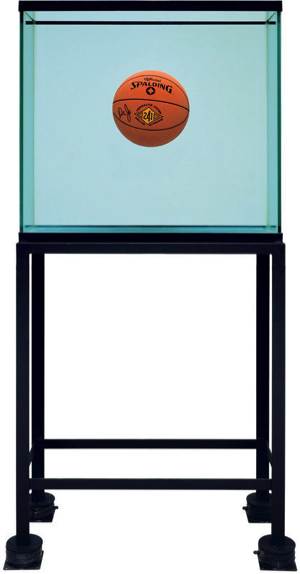

Professor Thomas Crow’s panoramic analysis of Koons moved away from the specifics of any one work or series, and instead identified an overarching conceptual theme he described as “multiple phase states.” By opening with Hans Haacke’s canonical Condensation Cube (1963–65), which the artist saw as akin to life as it reacts in parallel to its surroundings (not unlike Koons’s One Ball Total Equilibrium Tank or Three Ball 50/50 Tank, both from 1985), Crow traced Koons’s engagement with mutability from his early preoccupation with air (the Inflatables; the New) as it met with his investigation of water in Equilibrium. More telling, perhaps, is Koons’s appropriation of literal sublimation in Dr. Dunkenstein (1985), a Nike poster featuring a bisected basketball over which plumes of dry ice—a substance rare for turning from solid to gas without passing through a liquid phase—tumble downward. Seen alongside a keen awareness of life’s fragility and the endeavor to maintain its opposing state of eternal existence—a transformation Koons enacts in his bronze casts of inflatables—Crow brilliantly posited the analogy of an intermediate class of beings: deities. For Crow, the constant novelty Koons conjures in his work speaks, contrarily, to ancient attributes; immortality as an age-old means to surface, and deal with, the mutability of mortal human life. While the language of myth and of the divine realm is undeniably present in the work itself (the Nike sports heroes as “sirens”; the subjects, such as Pluto and Proserpina, of the recent Antiquity series), Crow instead takes his cues from less topical and more pervasive recurrent evidence in Koons’s oeuvre, citing widely and inclusive of the Shelton Wet/Drys (1981–87) and the notorious Balloon Dog (1994–2000), proffering a conceptual model distinctly apart from all that has come before and with the potential to powerfully redirect the Koons discourse.

Given the connotational elasticity of the verb to blow—for which the dictionary entry includes, among other definitions, “to be in motion, to move or run quickly; to send forth a current of air or other gas; to talk windily; to melt when overloaded; to shatter, burst, or destroy by explosion; to spend extravagantly”—the word seems apropos for the many readings and perspectives offered in The Koons Effect. In sequence, the verb stretches to encapsulate the vast range of topics addressed by the symposium (a mode of viewing Koons’s work in the galleries; a key element in an innovative interpretative framework; the artist’s unusual penchant to provide smoothly-delivered meanings for his works in frequently-given interviews; the surface appearance of the newest mirror-polished stainless steel sculptures; the explosion of methodology explored by this conference; and, of course, the literal viscera of the balloon works themselves) and helps to organize this diverse, sometimes unwieldy, and as yet not totally developed set of ideas into a neat(er) constellation. Whether Koons’s work can fulfill the same prophesy with yet another of its definitions, “to put out of breath with exertion,” remains to be seen. One certainly hopes not.

[…] Buhe, “Blowing Up the Koons Effect,” IFA Contemporary, September 25, […]

[…] Buhe, “Blowing Up the Koons Effect,” IFA Contemporary, September 25, […]