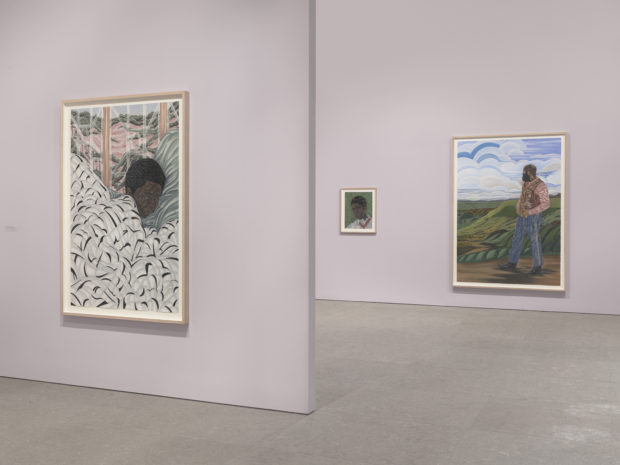

When visitors step into the Whitney’s first-floor gallery, which currently houses Toyin Ojih Odutola: To Wander Determined, they risk forgetting that they are standing in a museum. There is a softness to the space that distances it from the rest of the building, its warm lighting and the pink color of the walls evoking a feeling of intimacy that is both inviting and disorienting. A proclamation near the entrance, signed by artist Toyin Ojih Odutola in her role as “Deputy Private Secretary,” alerts viewers that the sixteen arresting works spread throughout the gallery are from the private collections of two aristocratic Nigerian families, the UmuEze Amara and Obafemi, connected through the marriage of the Marquess of UmuEze Amara, TMH Jideofor Emeka, and his husband, Lord Temitope Omodele. With this information, the intimate atmosphere is given context: it feels as if visitors have been transported to a private, family portrait gallery.

If not for the aforementioned, rather official wall text bearing the families’ crests, viewers would not know that Ojih Odutola’s subjects were of such prestigious social standing. Even armed with this knowledge, they are confronted with an incomplete narrative, left to question the identities of the elaborately fashioned figures in each portrait. No names are provided, nor are there any indications of the lineage from which each subject descends. What remains in their absence is a vague understanding that the subjects are related, as well as a desire to know how. Perhaps in other circumstances it would not occur to visitors to scrutinize the figures presented to them, but the context both provided and omitted by the artist’s proclamation incites a curiosity that may never fully be satisfied. This is the challenge that Ojih Odutola sets forth for her audience.

Should anyone wish to uncover more about these families, there are clues to explore. Titles can be helpful, but, in a remarkable display of “show, don’t tell,” it is the figures’ facial expressions and body language that tell us all we need to know. For instance, when one sees the title Newlyweds on Holiday (2016), the depiction of two unnamed men clad in lavish suits becomes the anchor that contextualizes the entire exhibition. With “newlyweds” as their only identifier, these figures, whose relationship to each other is indeterminable unless one ascribes significance to the closeness of their hands, are revealed to be the couple whose marriage joined the UmuEze Amara and Obafemi. On the other hand, the title Industry (Husband and Wife) (2017) doesn’t say nearly as much about its subjects as the visual impact of the couple facing away from each other, their estrangement equally evident in the husband’s displeased expression and the thin white barrier separating him from his wife.

The result is a story—a fictional one, first presented last year at the Museum of the African Diaspora’s exhibition entitled A Matter of Fact—that engages and perplexes. These families and the richness in detail that connects them are a fabrication through which Ojih Odutola subverts expectations of how stories are told. At the center of this story stands the interlocked emphasis of the formal and the conceptual in Ojih Odutola’s work. It is tempting to separate the two, focusing on either the images’ visual impact or their sociopolitical significance; however, the discussion of either in isolation would be incomplete, as each facet’s strength lies in that of its counterpart. A quick glance at Ojih Odutola’s Instagram feed reveals that her study of art history informs her work as much as her experience as an immigrant and as a black woman. It would be remiss not to address the fact that the life-size portraits of these figures are not paintings as they appear to be, but rather works on paper rendered in pastel, charcoal, and graphite. At the same time, they evoke thoughts of the European painting tradition of portraiture in which black figures are so absent. Likewise, conversations about race inspired by the artist’s handling of black pigment should involve attention to the aesthetic quality of her swirling, glowing, nearly animated rendering of skin, just as the lush colors and sinuous contours of the clothing and settings in which she places her subjects should be deliberated alongside questions of class.

The intricacy of the layers in Ojih Odutola’s examination of identity is mirrored in the strata that live beneath the topographical surfaces of her art. After hearing her speak about making these works, one understands the physicality of her process, the shape of each shadow revealing the corresponding movements of her arm. Every detail in her portraits is deliberate, and she dedicated equal consideration to their exhibition when collaborating with co-curators Rujeko Hockley and Melinda Lang. When relating how the show came to open at the Whitney, they describe Ojih Odutola’s crucial involvement throughout the process, from her choice of title to her presence during installation.

With the importance Ojih Odutola places on her artistic process and narrative in mind, the story of the UmuEze Amara and Obafemi becomes increasingly multifaceted. On the surface lies the most basic details in which a marriage joins two prominent families, whose likenesses are depicted in personal, yet sumptuous, portraits. Even the most candid images are meant to express the families’ nobility. Take for example the work entitled Surveying the Family Seat (2017), which shows a man looking out on a sprawling landscape. Despite his relaxed posture and inattention to the viewer, this image is a calculated statement of the man’s power and, by extension, that of his family. He is not merely on a walk, but also, as the title notes, observing the state of this family-owned land, which, depending on his position in the family and the order of succession, may one day be inherited by the newlyweds.

Complications to the fictional narrative arise when one contemplates the effect of this marriage on joint family assets, particularly when confronted with illegality of homosexuality and, consequently, gay marriage in Nigeria. Since the connection between the UmuEze Amara and Obafemi families, not to mention existence of this exhibition, is contingent upon the marriage of the Marquess and his husband, the disconnect may give pause to those aware of it. As notable as this conflict between fiction and reality is, neither illegality nor illegitimacy is acknowledged in the exhibition space, in which emphasis is placed on the images themselves. This omission is intentional, as Ojih Odutola stated about the relationship of her narrative to the criminalization of homosexuality in Nigeria: “I just wanted two gay men to be the grand lords who are imparting their family history together. That, to me, shouldn’t have to be political. I would just like people to walk through and not even think about it. That’s when I know I’ve succeeded.”[1] That isn’t to say that these works are inherently apolitical. On the contrary, Ojih Odutola’s hope to present these subjects in a way that she deems “unremarkable”[2] in a political climate where the disparity between privileged and oppressed identities, including but certainly not limited to race, class, and sexual orientation, is so prevalent exposes the effort necessary for her to achieve this goal.

Nonetheless, Ojih Odutola rises to the challenge. Her successful navigation of the sociopolitical and formal aspects of her work, as well as the dichotomy between reality and fiction in her narrative, is arguably most evident in her Wall of Ambassadors (2017). In this work the viewer sees through the eyes of one of the subjects, perhaps a family member, whose hands grasp a flower-filled vase at the bottom of the frame. This person and the viewer stand before a wall of portraits in oval frames. Of the three fully visible portraits, two are rendered in color, one in black and white, the latter of which surely belongs to an earlier time than the others. The central portrait, the largest of the three, is the only one that makes eye contact with the viewer, who may have difficulty looking away. Once more, Ojih Odutola’s mastery of color and contouring permeates the scene. Additionally, her depiction of portraits that resemble photographs within a scene that feels like a painting deepens the deception of her medium. She also introduces spatial layering, the figures within the frames, the frames on the wall, the person holding the vase, and the viewer each inhabiting a different dimension. Similarly, she layers time: within one scene, she presents a synoptic view of the family’s history, past and present generations inhabiting the same space.

The longer one looks at this work, the more of its layers are uncovered. In the same way, the complexity of To Wander Determined demands multiple visits. Whether motivated by the incredulity that the uniquely stylized portraits are not the paintings they originally appeared to be or by a desire to connect the strands of the narrative that Ojih Odutola presents, visitors will return time and time again to find themselves just as spellbound as they were when they first entered the gallery.

[1]. Felsenthal, Julia. “At the Whitney, a Vision of Africa – Without the Colonialist Meddling.” Vogue, October 17, 2017. https://www.vogue.com/article/toyin-ojih-odutola-whitney-museum-interview.

[2]. Ibid.

This is such a beautiful piece! Thank you! My fave of Toyin pieces is the Bride!