“The horror of looking is not necessarily in the image but in the story we provide to fill in what is left out of the image.” -Marianne Hirsch [1]

A recent survey conducted in February 2018 by the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany found that 49% of Millennials cannot name a single concentration camp or ghetto among the dozens that operated during the Holocaust.[2] Just one month after the survey’s results became public, an exhibition of California-based artist Natalie Arnoldi titled This Happened Here opened at Charlotte Jackson Fine Art. Five large-scale paintings by Arnoldi, which were not for sale, went on view from March 9th – 31st at the gallery in the trendy Railyard District of Santa Fe, New Mexico. These five paintings offer one avenue through which contemporary art can minimize the distance between a contemporary public and a historical event like the Holocaust.

An obscure, grainy oil painting of railroad tracks descending into the bleak distance rendered in greys, whites, and blacks titled Helix (2012) functioned as the meaningful starting point of the exhibition. A few years ago, a woman visited the studio of artist Charles Arnoldi, Arnoldi’s father, where one of his daughter’s train track paintings was hanging. Upon viewing Arnoldi’s painting, the woman burst into tears. She explained that her grandmother was a survivor of Auschwitz-Birkenau and that the work had reminded her of her grandmother’s arrival to the camp. Her reaction is a potent reminder that art does not exist in a vacuum. It is also a profoundly interesting example of the power of post-memory.

Marianne Hirsch, professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University, uses the term “post-memory” to define the relationship of descendants of Holocaust survivors to the horrific, traumatic experiences that their ancestors endured. Despite the fact that these events occurred before their birth, Hirsch proposes that the traumatic memories of their ancestors were “transmitted to them so deeply as to constitute memories in their own right.”[3] When the train tracks leapt out of Arnoldi’s painting and disturbed the woman to tears, she was accessing post-memories. The haunting image that emerged from the painting became the woman’s own emotional memories, not just those of her grandmother. Hirsch writes that in regard to images of the Holocaust, “the horror of looking is not necessarily in the image but in the story we provide to fill in what is left out of the image.”[4] Inspired by the story that this woman ascribed to Arnoldi’s simple painting of train tracks amidst fog, the artist embarked on her own journey with the history of the Holocaust.

As she read numerous books and delved into the archives of museums and educational institutions, Arnoldi became interested in the historical photographs taken of the Nazi concentration and death camps after their liberation. As they are based on these photographs, her paintings are devoid of people or activity. In a phone interview, the artist described how the photographs taken by the allied forces as they liberated the camps symbolized for her the moment in which a global community realized what had truly happened. The smallest painting is scaled at eight feet by eight feet while the largest is eight feet by sixteen feet. The large-scale works envelop you, making you feel as though you are entering the spaces being depicted. April 29 (2016) features a large industrial open door with the words “Brausebad” above its frame, while January 27 (2016) depicts an empty chamber with pipes snaking along its ceiling. Despite the fact that critic Michael Abatemarco wrote in the Santa Fe New Mexican that “the recent paintings may represent specific rooms gleaned from photos and visits to existing locales, but they offer no explanation, history lesson, or critique of what they depict,” the artist wrote descriptive historical information for each painting in a gallery guide provided in the space.[5] Moreover, Arnoldi imitates the photographs, depicting the hollow emptiness of these spaces in order to index the horror of what occurred there and therefore critique it. Just as the woman who evidenced post-memory, the paintings require us to do the work of filling in the story of what “happened here.”

Interestingly, Hirsch wrote that “Photography is precisely the medium connecting memory and post-memory.”[6] She elaborates that photography reveals memory and post-memory as constructed by narration and imagination. Arnoldi mobilizes the very medium that Hirsch associates with post-memory, however she translates it into painting. A gray-scale fog permeates the composition, rendering the image unclear and slightly abstracted. In this aesthetic gesture Arnoldi reveals the constructed, mediated nature of the image. She does not offer us a mimetic image of genocide or the spaces in which it occurred. Theorists addressing aesthetics after the Holocaust, such as Theodor Adorno, have written about the dangers of attempting to recreate images of the horrific event. In Adorno’s words: “The so-called artistic representation of the sheer physical pain of people beaten to the ground by rifle butts contains, however remotely, the power to elicit enjoyment out of it.”[7] Arnoldi avoids this issue by focusing instead on the intractability of the spaces in which the physical pain of people occurred. Her paintings are negotiated, abstracted depictions just as our relationship to these spaces is mediated through narration, imagination, and the elusive nature of memory. This is not to say that she ignores the violence, but rather she offers a “doorway” into thinking about these spaces and what occurred there. Our interaction with the large-scale works is quiet and introspective precisely because they are void of action.

Part of the artist’s desire to do this was to try to confront her viewers with something similar to the empathic feeling of actually inhabiting these spaces, which are of course similarly empty of the violence that once occurred within them. When Arnoldi made the paintings in the exhibition, she had never visited the concentration camps in person. In fact, as critic Iris McLister wrote in the Santa Fe Reporter: “It may come as a surprise, given the work, that neither the artist nor the gallery owner is Jewish.”[8] It is unfortunate that McLister assumes only a Jewish artist or gallerist would be interested in creating or displaying artwork related to the Holocaust. Perhaps even more unfortunate is another statement that McLister made: “We’re compelled to respond emotionally – and that feels somewhat ruthless.”[9] Rather than “ruthless” I would argue that Arnoldi’s works are generous in that they provide her viewers with the opportunity to respond emotionally. At the same time, maybe art of this nature should be ruthless. When 49% of Millennials cannot name a single concentration camp while generations of Jews live with post-memory and therefore a post-generational sense of trauma, viewers might need to be compelled to relate emotionally to this history.

Many communities who have experienced historic trauma often evidence post-generational trauma. Scholars such as Marita Sturken have discussed its prevalence in Japanese-Americans whose ancestors were interned during the Second World War, while Joy DeGruy has explored its impact on African-Americans today.[10] Post-memory affects those inhabiting the same spaces as us, yet it is often not discussed. Arnoldi had never thought deeply about the Holocaust until a woman revealed the impact of post-generational trauma through one bout of tears. After the artist created the four paintings in the gallery show, she decided to visit the concentration camps herself. The paintings on view in This Happened Here symbolize not just the power and prevalence of post-memory but also the way in which someone who is not experiencing post-generational trauma can find a way to empathize with those who are. Contemporary art like Arnoldi’s has the power to create an empathic experience and lessen the distance between her viewers and a historical event like the Holocaust.

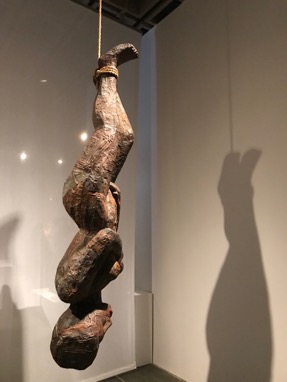

While these paintings are not on view in New York, those who are interested in similar artwork should visit the group exhibition titled Violated: Women in Holocaust and Genocide at Ronald Feldman Gallery, which is comprised of works testifying to the sexual violence endured during the Holocaust and later genocides. Finally, to try to establish an understanding of how post-memory affects those around us, we can also think about Alison Saar’s sculpture on view in the Met Breuer’s current exhibition Like Life, Sculpture, Color, and the Body. Strange Fruit (1995) was inspired by a lynching evoked through a song of Billie Holiday’s. We are not as far from historic trauma and its affect as we may feel, and contemporary art like that of Natalie Arnoldi’s can help us connect to this imperative fact. I leave you with the words of an anonymous Polish visitor to Arnoldi’s exhibition, who wrote in the gallery’s guestbook: “Natalie…you have reached across time & timeless morality and touched my soul and those of people who spend time viewing your work. Maybe these can help us continue to shed the awful detritus of our collective insanity.”

[1] Marianne Hirsch, “Family Pictures: Maus, Mourning, and Post-Memory.” Discourse 15, no. 2 (Winter 1992-3): 7.

[2] “New Survey by Claims Conference Finds Significant Lack of Holocaust Knowledge in the United States.” Claims Conference (February 23 -27, 2018). http://www.claimscon.org/study. (Accessed April 23, 2018).

[3] Marianne Hirsch, “The Generation of Postmemory”. Poetics Today 1 March 2008; 29 (1): 103–128. doi: http://doi.org/10.1215.03335372-2007-019. Page 103.

[4] Hirsch, “Family Pictures: Maus, Mourning, and Post-Memory.” 7.

[5] Michael Abatemarco. “Missing information: the Holocaust paintings of Natalie Arnoldi.” Pasatiempo. (March 16, 2018). http://www.santafenewmexican.com/pasatiempo/art/missing-information-the-holocaust-paintings-of-natalie-arnoldi/article_b1d16b26-c7bb-5706-b786-141d0b1c99f5.html. (Accessed April 27, 2018).

[6] Marianne Hirsch, “Family Pictures: Maus, Mourning, and Post-Memory.” Discourse 15, no. 2 (Winter 1992-3): 9.

[7] Theodor Adorno, “Toward a New Categorical Imperative” in Theodor Adorno and Rolf Tiedemann. Can One Live After Auschwitz?: A Philosophical Reader. Stanford University Press, 2003. 312.

[8] Iris McLister. “Obscured: New work from California’s Natalie Arnoldi may leave you more shaken than stirred.” Santa Fe Reporter. (March 6, 2018). https://www.sfreporter.com/arts/2018/03/07/obscured/. (Accessed April 27, 2018).

[9] Ibid.

[10] See Marita Sturken, “Absent Images of Memory: Remembering and Reenacting the Japanese Internment.” positions 5, no. 3 (August 1997): 687–707. doi: https://doi.org/10.1215/10679847-5-3-687.; David Love, “Post-Traumatic Slave Syndrome and Intergenerational Trauma: Slavery is Like a Curse Passing Through the DNA of Black People.” Atlanta Black Star. (June 5, 2016) http://atlantablackstar.com/2016/06/05/post-traumatic-slave-syndrome-and-intergenerational-trauma-slavery-is-like-a-curse-passing-through-the-dna-of-black-people/. (Accessed April 27, 2018).

Be First to Comment