Never shy about her political stance, Beyonce openly endorsed candidate Hillary Clinton in the 2016 presidential election, making clear her belief that the future is female. Her album Lemonade, which Beyoncé produced the same year and complemented with powerful video content, illustrates her feminist stance through explicitly political, but also personal references.

One of the most memorable scenes from Lemonade is the second song Hold Up. Here, Beyoncé elegantly steps out of a neoclassical building followed by an overflowing mass of water. Then, she jubilantly leaps onto a street, where she takes a baseball bat away from a child and begins to smash the windows of the cars parked on the side of the street. This unexpected twist of tone departs from the innocent ecstasy evoked in the first scene reminds me of Pipilotti Rist’s 1997 video work Ever is Over All. Here, a woman in a blue dress gleefully walks down a street before, all of a sudden, starting to smash cars’ windows with a long flower stem.

Both in positive and negative ways, many critics and spectators have identified the striking similarity between the Swiss video artist’s work and this particular scene in Lemonade. Although Beyoncé has not yet admitted the connection between her work and Rist’s, the two artists spark a conversation about feminism through a visualization of destruction that is almost identical. Already in an essay written in 1980, art historian Lucy R. Lippard describes the act of smashing windows as a powerful feminist trope.[1] In the society where women’s voices are constantly being silenced, creating chaos seems to be the only way to be heard. In this sense, both Beyoncé and Rist’s display of violence communicates frustration, but also empowerment, to the point that the act of smashing windows can be taken to visualize the destruction of the patriarchy to prepare the ground to reconstitute an alternative sociopolitical order.

However, there is a significant difference between these two films, embodied by the smiling policewoman in Rist’s Ever is Over All. Unlike Rist’s performance, Beyoncé’s defiant action is situated within the impoverished realm of a community which is the primary target of social injustice and police brutality. In the political context of Lemonade, it is impossible to imagine a policewoman smiling and nodding to a black woman who is smashing windows. On the contrary, Beyoncé’s work evokes the concrete reality of police brutality and racial profiling, as well as the riots that ensued as ensuing their tragic consequences, as it happened in Ferguson, Missouri in 2014 after a police officer shot and killed unarmed 18-year-old Michael Brown. Instead of a complying cop, Lemonade stages a stunned but inspired black woman, whose impressed features fill the camera’s close-up view.

This interesting replacement can be interpreted as an invitation to discuss feminism with an intersectional perspective that is absent in Rist’s work. Through her references to African American communities and racial segregation, Beyoncé suggests that for black women feminism seems to be more than fighting for gender equality; it involves fighting for racial justice as well.

Initially, Beyoncé invited video artist Kahlil Joseph to co-direct Lemonade, a collaboration that, according to The New Yorker, was “based on the aesthetic truths of blackness and of mourning.” [2] Joseph’s version conveyed impressions of tenderness and vulnerability which are absent in the album’s final version. Clearly, Beyoncé was not interested in Joseph’s victimizing depiction of a heartbroken woman mourning her husband’s infidelity, an image modeled on the rumored problems with her own partner. Rather, the pop star was resolved to communicate a more empowering message, showing that people, and especially black women, can turn the hardship in their lives into a liberatory statement: a statement claiming that women like her are unbreakable despite the disadvantages posed by their gender and race.

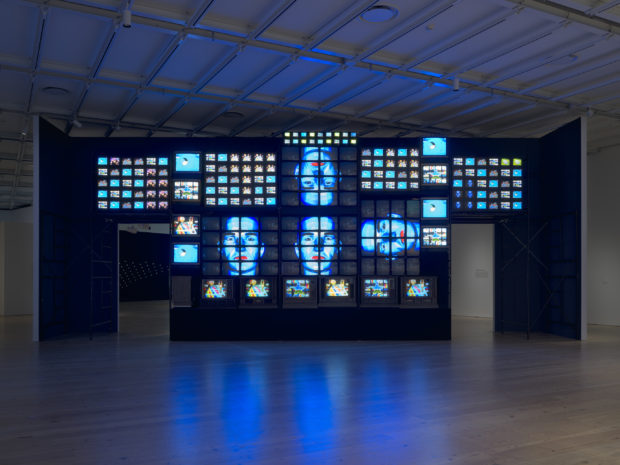

Beyoncé’s decision to include the mothers of some of the African Americans recently executed by the police (Michael Brown, Trayvon Martin, and Eric Garner) during the song Freedom emphasizes her commitment to address the theme of race alongside that of gender.[3] In the film, these brave but grieving women are dressed in traditional African fineries holding pictures of their deceased sons. Their glorified pain appears as a testimony to the racism that still pervades the United States’ social and political life. This excerpt of Lemonade calls to mind another video artwork: Arthur Jafa’s Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death (2016). Through this film, which unfolds seven minutes of seemingly random images, viewers are forced to witness and confront social injustice over and over again. Montages of police officers shooting African Americans intermix with footage of president Obama singing Amazing Grace and the performances of African American musicians. These scenes, similarly to Lemonade, evoke the ambivalent celebration of black identity alongside the pain that ensues from racial persecution. The back and forth from the joy and pride conveyed through music to the frustration and grief generated by police brutality aligns with Beyoncé’s directing strategy.

Indeed, Beyoncé elevates mere understanding of the gender equality aspect of feminism to a more holistic level of intersectional feminism. Besides her dedication to underscore the double oppression to which black women are subjected, the pop star also engages in the creation of an optimistic model for modern femininity to which all of her viewers, regardless of race, sex, and gender, can aspire. This optimism, desperately needed in our society, fulfils the latent demand of thousands of people around the world who recognize the imbalances addressed in Lemonade. Besides confirming Beyoncé’s excellence as a performer, the commercial success of the album demonstrates the urgency and ubiquity of the sociopolitical themes that it addresses. The invincible “Queen Bey” is not afraid of smashing windows, and I believe that, with the hope that she instills in us, the glass ceiling will soon be broken.

[1] Lucy R. Lippard, “Sweeping Exchanges: The Contribution of Feminism to the Art of the 1970s,” Art Journal 40, no. 1/2 (1980): , doi:10.2307/776601.

[2] https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/11/06/the-black-excellence-of-kahlil-joseph

[3] Victoria M. Massie, “6 black women Beyoncé channels in Lemonade – from Warsan Shire to Zora Neale Hurston,” Vox, April 26, 2016, , accessed December 02, 2017, https://www.vox.com/2016/4/26/11501466/beyonce-lemonade-warsan-shire.

Be First to Comment