Bruce Nauman: Disappearing Acts opened in March at the Schaulager Museum in Basel, Switzerland, to rave critical reviews and social media buzz. Here in New York, the work is presented in two parts between the Museum of Modern Art and MoMA PS1, and although the curators refrain from calling it a retrospective, according to the museum website it is “the most comprehensive exhibition of the artist’s work ever assembled.” The curatorial team undoubtedly grappled with the challenge of presenting the difficult conceptual content of Nauman’s work to a large and diverse public. Although the distribution of works between two locations would seem to disrupt the continuity of the exhibition, the curators use this feature to their advantage; the installation at the MoMA develops concepts that are explored in greater depth at PS1, allowing us to recognize thematic cohesion across Nauman’s diverse body of work.

The midtown MoMA display organizes the artist’s career into loosely chronological phases. The show begins just outside the galleries with Venice Fountains (2007), a work that highlights Nauman’s disdain for classical art and his embrace of the readymade. These fountains feature cast plaster molds of the artist’s face, and water streams from their mouths into dingy white sinks, creating a hollow splashing that provides an auditory backdrop to the opening wall text and effectively introduces sound as a major component of Nauman’s work. The work also demonstrates Nauman’s willingness to offer his own body as the antithesis to the physical ideals of classical sculpture.

The galleries at the beginning of the exhibition highlight Nauman’s 1960s explorations of the body. In these works, the artist renders limbs in hydrocarbon wax, an unnervingly flesh-like material that emphasizes the gracelessness of the human form. He more explicitly objectifies the human form in works like Neon Templates of the Left Half of My Body Taken at Ten-Inch Intervals (1966), which translates the body into pure referent. As we move into the larger galleries, our own bodies unexpectedly become the subject of Nauman’s manipulations. Going Around the Corner Piece (1970) features a four-walled structure with a monitor and a security camera on each side. I approached a monitor expecting to see myself—or perhaps a video of the artist—but soon realized with some discomfort that I was surreptitiously watching the activities of other gallery occupants “around the corner” and out of sight from my own vantage point.

Although large sculptures visually dominate the gallery, I felt most compelled by Nauman’s installation Six Sound Problems for Konrad Fischer (1968). The artist diverts the circulation of tape through the player to loop around a pencil taped to a chair several feet away. According to the wall label, the sounds emitting from the tape were recorded by Nauman while he performed “basic activities” such as pacing, bouncing a ball, and playing a violin. In its original installation at Konrad Fischer’s Düsseldorf gallery, Six Sound Problems played a different sound every day except for Sunday, when it was turned off. The MoMA has adhered to these original guidelines, and this particular Wednesday afternoon I was subjected to the high-pitched drone of off-key violin, the noise filling every corner of the gallery and inhibiting my ability to process the other works. Nauman engineered these soundtracks to most effectively penetrate the space; a pencil diagram accompanies the piece, showing how he adjusts the position of the chair and therefore the length and angle of the tape to best suit the sound of the day. Although Nauman’s use of pre-recorded sounds would seem to remove artistic agency from the piece, he closely directs our experience of the work; its permutative quality hints at ideas developed elsewhere in the exhibition.

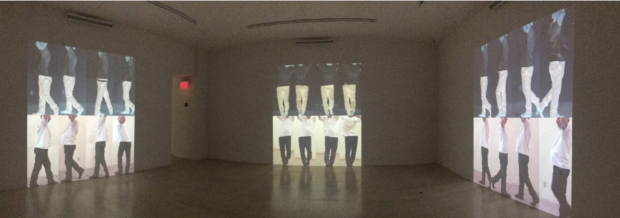

The works on view at PS1 hone in on Nauman’s interest in the legacy of Conceptual art and the body as a site of subjective assessment. Spread across three floors, we become witness to and participants in Nauman’s social and psychological experiments that challenge the extent to which the objective or absent artist can incite a subjective response. In works like Contrapposto Studies i through vii (2015/2016), installed on the first floor, the artist’s body is subjected to fragmentation, permutation, and repetition in a way that flattens and depersonalizes it. Nauman filmed himself walking in an exaggerated fashion, twisting his body with each step into the contrapposto pose common in classical sculpture. With each successive “study” he further fragments his own form, splicing himself back together imperfectly so that each section becomes its own entity. Classical representations of the body flatten through their subjective idealization of the human form, depicting types rather than individuals. Tongue in cheek, Nauman subverts this reference and subjects his own aging, imperfect form to the contrappostal pose, reflattening the body through fragmentation and permutation into a site of objective manipulation.

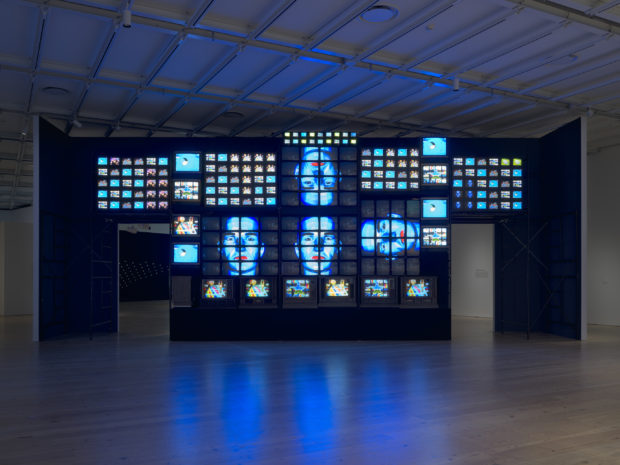

Nauman seems interested in the desire of Conceptual artists to remove their own subjective artistic expression from their work and rely on chance, permutation, diagrams and directions. Subjectivity itself becomes his medium as his work incites specific physical and psychological reactions through conscious manipulation of our experience. As I stepped into Double Steel Cage Piece (1974), I became the performer as I edged my way through the narrow passageway around the structure’s perimeter, my slow progress on display for everyone else standing in the gallery. Not only was I enacting a series of movements prescribed by the dimensions of the work, I was also experiencing a set of emotions engineered by the experience: embarrassment, claustrophobia, slight panic. I imagine that other visitors experience similar feelings, universal biological responses to such spatial constraint. For Good Boy, Bad Boy (1985) Nauman tries a different tactic. Two actors read a series of evaluative statements, their tone and volume directing meaning. As we realize they are merely reciting a prescribed set of words, meaning flattens, regardless of their tone. Nauman deflates socially charged concepts like goodness, badness, virtue, sex, love, and hatred, rendering them mere sounds without signage.

Some critics suggest that Nauman’s deft manipulation of our response to his work reflects close attention to the social and political issues of the day. Jacolby Satterwhite’s discussion of Nauman’s work in last month’s Artforum focuses on the artist’s video work, attributing his “self-objectification” to a desire to interrogate his status as a white male. Nauman began his work in the 1960s, a time when “much of the conversation centered on the right [of black people] to occupy public spaces…This appeal for universal access penetrated the zeitgeist, and it continues today…Nauman’s work can be understood within this context as an interrogation of the banality of his white male body: its scale, identity, and relationship to his environs.” [1] This narrative is largely absent from the MoMA’s presentation of Nauman’s oeuvre. The curators perhaps felt that to attribute explicit social content to the artist’s work would be to obscure its more conceptual content, difficult enough to convey without adding these charged overtones.

However, Nauman’s explorations of subjectivity and objectification, both of himself and of the viewer, remain relevant to our current social and political moment. Satterthwaite refers to Rosalind Krauss’s 1976 essay Video: The Aesthetics of Narcissism, in which Krauss observes that video differs from the other visual arts in its “capability to record and transmit at the same time—producing instant feedback.” [2] This creates a “prison of a collapsed present, that is, a present time which is completely severed from a sense of its own past.” Nauman enacts this collapsed present or self-encapsulation not only on himself but on the viewer, and as this exhibition demonstrates, he has extended his reach outside of the video medium. Experiencing works like Going Around the Corner Piece, Six Sound Problems, Double Steel Cage Piece, and Good Boy, Bad Boy (1985), I felt unable to control my own image, thoughts, physical space, or values. The exhibition shows us how the artist exposes and objectifies not only our bodies but our inner selves, and we leave the museum with a healthy dose of dread.

In his essay for Artforum, Ken Okiishi observes that Nauman’s work adapts to the age of social media, and that the artist’s methods of self-objectification recall “social media’s tactic of isolating the insta-live image, blocking off everything else to intensify the impact and encourage an immediate affirmative response.” [3] This manufactured isolation of the senses to produce a calculated response is repeated throughout the artist’s career. Perhaps Nauman problematizes his status as a white male through a larger attempt to demonstrate how little control we have over the construction of our identities, even the identities we create for ourselves. A number of critics have marveled at Nauman’s continued relevancy, perhaps partially attributable to the insta-generation’s affinity for neon (even midweek at the MoMA, a line of museum-goers waited to take a photo in front of 100 Live and Die [1984]). More importantly, however, Nauman reveals the futility of assigning value judgements to the body altogether, a project that seems particularly relevant to our tense political moment.

Footnotes:

1. Jacolby Satterwhite, “Out of Your Head: The Art of Bruce Nauman,” Artforum 57, no. 2 (October, 2018): 180.

2. Rosalind Krauss, “Video: The Aesthetics of Narcissism,” October 1 (1976): 51–64. www.jstor.org/stable/778507.

3. Ken Okiishi, “Out of Your Head: The Art of Bruce Nauman,” Artforum 57, no. 2 (October, 2018): 174-178.

Be First to Comment