Gothic Spirit: Medieval Art from Europe, on view through March 7, 2020 at Luhring Augustine and presented in partnership with London-based gallery Sam Fogg, features… Continue Reading Making Medieval New: “Gothic Spirit” at Luhring Augustine

Posts published in “Reviews”

Pictured on street corners and plastered throughout the metro system, an eye-catching image announcing the Fondation Louis Vuitton’s current exhibition Charlotte Perriand: Inventing a New World… Continue Reading Charlotte Perriand: Pioneering Design in a Man’s World

Walking into The Frick Collection, one is met with a historic setting in which to view a wide range of paintings, sculptures, decorative arts, and… Continue Reading Reworking Spaces: “Elective Affinities: Edmund de Waal” at The Frick Collection

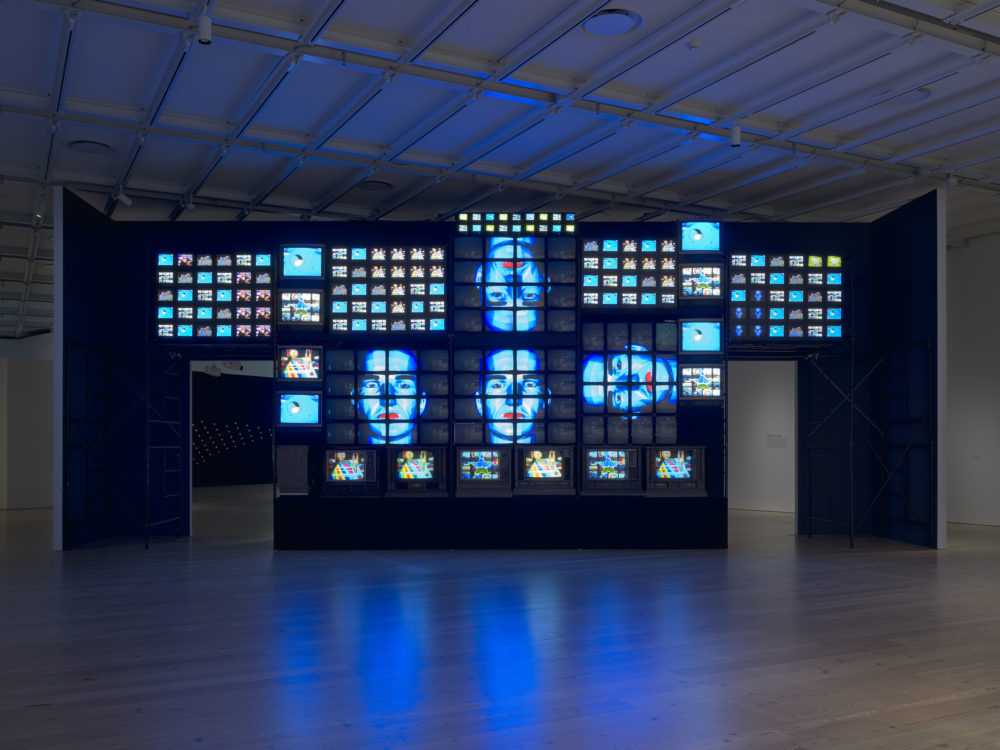

Drawing heavily from the Whitney Museum of American Art’s permanent collection, Programmed: Rules, Codes, and Choreographies in Art, 1965–2018 includes a broad range of works… Continue Reading A Daring Balancing Act: “Programmed” at the Whitney

Despite a month of chilling temperatures, Joan Semmel’s captivating new paintings on view in A Necessary Elaboration at Alexander Gray Associates (January 10 – February… Continue Reading Reflections on the Body and Self in Joan Semmel’s New Paintings

Bruce Nauman: Disappearing Acts opened in March at the Schaulager Museum in Basel, Switzerland, to rave critical reviews and social media buzz. Here in New… Continue Reading Master Manipulator: Bruce Nauman at MoMA

Addressing themes not often united in contemporary art exhibitions, the Bronx Museum of the Art’s stellar presentation of Diana Al-Hadid: Delirious Matter (July 18—October 14,… Continue Reading Fleeting Structures: Diana Al-Hadid at the Bronx Museum

“The horror of looking is not necessarily in the image but in the story we provide to fill in what is left out of the image.” -Marianne Hirsch [1]

A recent survey conducted in February 2018 by the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany found that 49% of Millennials cannot name a single concentration camp or ghetto among the dozens that operated during the Holocaust.[2] Just one month after the survey’s results became public, an exhibition of California-based artist Natalie Arnoldi titled This Happened Here opened at Charlotte Jackson Fine Art. Five large-scale paintings by Arnoldi, which were not for sale, went on view from March 9th – 31st at the gallery in the trendy Railyard District of Santa Fe, New Mexico. These five paintings offer one avenue through which contemporary art can minimize the distance between a contemporary public and a historical event like the Holocaust.

An obscure, grainy oil painting of railroad tracks descending into the bleak distance rendered in greys, whites, and blacks titled Helix (2012) functioned as the meaningful starting point of the exhibition. A few years ago, a woman visited the studio of artist Charles Arnoldi, Arnoldi’s father, where one of his daughter’s train track paintings was hanging. Upon viewing Arnoldi’s painting, the woman burst into tears. She explained that her grandmother was a survivor of Auschwitz-Birkenau and that the work had reminded her of her grandmother’s arrival to the camp. Her reaction is a potent reminder that art does not exist in a vacuum. It is also a profoundly interesting example of the power of post-memory.

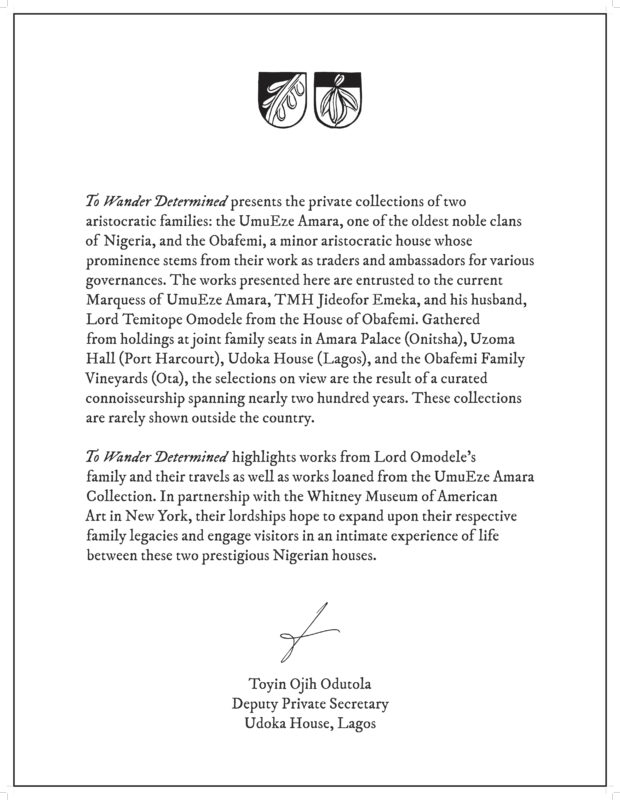

When visitors step into the Whitney’s first-floor gallery, which currently houses Toyin Ojih Odutola: To Wander Determined, they risk forgetting that they are standing in a museum. There is a softness to the space that distances it from the rest of the building, its warm lighting and the pink color of the walls evoking a feeling of intimacy that is both inviting and disorienting. A proclamation near the entrance, signed by artist Toyin Ojih Odutola in her role as “Deputy Private Secretary,” alerts viewers that the sixteen arresting works spread throughout the gallery are from the private collections of two aristocratic Nigerian families, the UmuEze Amara and Obafemi, connected through the marriage of the Marquess of UmuEze Amara, TMH Jideofor Emeka, and his husband, Lord Temitope Omodele. With this information, the intimate atmosphere is given context: it feels as if visitors have been transported to a private, family portrait gallery.

If not for the aforementioned, rather official wall text bearing the families’ crests, viewers would not know that Ojih Odutola’s subjects were of such prestigious social standing. Even armed with this knowledge, they are confronted with an incomplete narrative, left to question the identities of the elaborately fashioned figures in each portrait. No names are provided, nor are there any indications of the lineage from which each subject descends. What remains in their absence is a vague understanding that the subjects are related, as well as a desire to know how. Perhaps in other circumstances it would not occur to visitors to scrutinize the figures presented to them, but the context both provided and omitted by the artist’s proclamation incites a curiosity that may never fully be satisfied. This is the challenge that Ojih Odutola sets forth for her audience.

The Usable Past: “The concept that a self-conscious examination of historical figures, moments, and symbols can shape current and future political formation.”[1]

This is how the Whitney defines the title of one of five galleries in their ongoing permanent collection exhibition An Incomplete History of Protest. The works in the gallery present memory and nostalgia as both powerful and yet often insufficient vehicles to re-experience the past. Sharing tropes of obfuscation and anonymity, the works materialize the incomplete nature of memory and documentation.

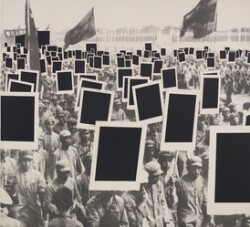

Annette Lemieux’s painting Black Mass (1991), in which she replaces the protest signs in a civil rights march with black, empty squares, hangs across the room from Glenn Ligon’s Untitled (Speech/Crowd) #2, a photograph of the Million Man March which Ligon has blurred and layered with coal dust. These works recall acts of censorship and evoke the fading hope of social change in a world where battles for civil rights must be repeatedly fought. However, the works in the exhibition that truly express the concept of “the usable past” are those which feature the museum as their main subject.

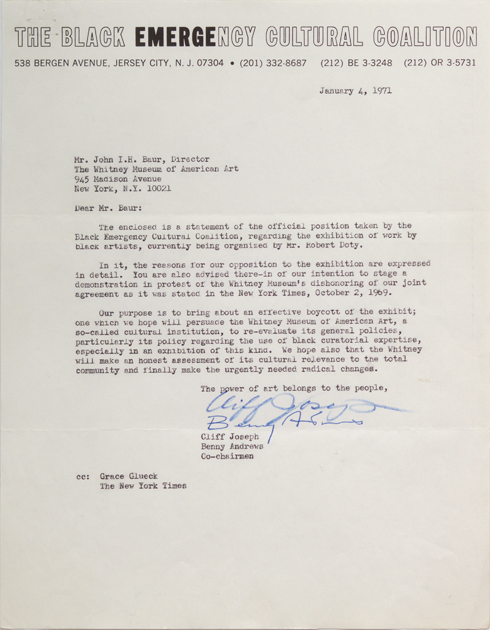

Lining the walls of the museum’s new Meatpacking building, a multiplicity of letters of protest written to the Whitney by artists and organizations related to the institution emerge from the Whitney’s archives. In a letter from 1971 addressed to former director John I.H. Baur, the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition announced their opposition to the 1971 exhibition Black Artists in America and declared their plans to demonstrate on the museum’s premises. Their initial discontent stemmed from the Whitney’s seemingly empty promise to hire and consult with black art leaders for the curating of the show. The BECC’s correspondence with the Whitney attests to the fact that the institution has dealt with issues surrounding the cultural agency of marginalized groups in an art context. Alongside this letter, dozens of other requests from artists implore the museum to remove their work as acts of protest or solidarity during moments of political unrest, and urge the museum to take a stance on current socio-political debates.