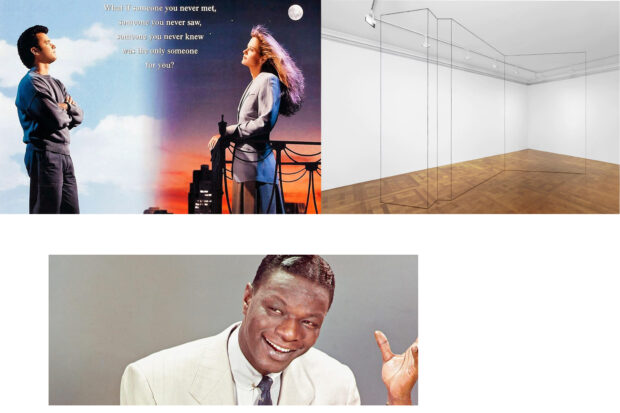

Right: Wade Guyton, Untitled, 2006. Epson UltraChrome inkjet on linen, 89 × 54 in. (226.1 × 137.2 cm). Private collection. © Wade Guyton. Photograph by Lamay Photo. Image courtesy whitney.org.

Wade Guyton is, in many ways, an art historian’s artist. He engages with the questions that get us going: questions of aesthetics, medium specificity, and the iconography of modernism itself, not to mention the very directness with which he prompts his viewers to wonder what’s “relevant” in art today. Lots of ink has been spilled attempting to define Guyton’s artistic practice, and many have asserted his status as a painter. A painter who, despite his use (primarily) of Epson inkjet printers and tabletop scanners, tips his hand both by very consciously employing that ur-signifier of painting—canvas plus stretcher bar—and by articulating the limits of his medium. Guyton’s current retrospective at the Whitney (on view October 4, 2012 to January 13, 2013) gives us an opportunity to re-examine these interpretative strictures and consider the work through the varied art-historical lenses that it demands.

Guyton is an artist who engages in diverse modes of artistic production: one who very intelligently picks and chooses the sly winks he makes toward the history of twentieth-century art, in all its forms. He does this both literally (his use of modernist abstraction from the likes of Martin Kippenberger, Mies van der Rohe, and Sam Francis as the ground for his printer drawings) and conceptually (in taking on questions of methodology and ontology that haunt these various media). Self-admittedly, Guyton makes sculptures, paintings, photographs, and installations, though he is much more comfortable employing these descriptors in reference to the works than in reference to himself (painter, sculptor, photographer). One way to parse Guyton’s artistic practice, then, might be to read it through these varied histories of art. Foremost among these concerns for Guyton’s work, it seems to me, is photography.

Immediately and emphatically clear upon encountering many of Guyton’s pieces is that he uses contemporary technology: the computer, the scanner, the printer, and basic image manipulation programs. His vocabulary of X’s, U’s, dots, bands, stripes, and blocks comes directly from the software of our everyday technological apparatuses, like Microsoft Word, while the vocabulary that doesn’t—the ripped-out book pages showcasing high modernism; a book’s endpaper or dust-jacket—is nonetheless mediated by the printer’s marks or the scanner’s lens.

The scanner is a dumb technological device insofar as it needs an operator; it reads and captures only what is placed atop its clear glass bed. The camera does something similar, framing and recording only what it is asked to see. In both cases the product can be said to be subjectively documentary. Both assert, “This happened.” The photograph records a lived, historical moment in time; the printout records what was once on Guyton’s scanner and/or computer screen. (Especially relevant in this regard are drawings, mostly from 2011, in which Guyton printed out whatever was on his monitor, often a story from nytimes.com, in a self-reflexive conflation of these two documentary assertions. Further noteworthy is that the first image in the Whitney’s catalog is a screenshot of Guyton’s desktop. Sunday, 4:16PM.)

Camera is to scanner as photograph is to printer painting, all its misalignments, spatters, and empty spaces included. For both the camera and the scanner, the medium in question is dispersed. Painting is to paint as photograph is to light, to chemicals, to camera. Guyton’s hand is present in the selection, the framing, the culling, and in on the content of the screen: the juxtapositions, layerings, tonalities, saturations, and enlargements. These latter processes bear striking resemblance to darkroom edits; burn, dodge, superimpose. In this sense, despite the scanner’s proclivity to capture everything it sees, Guyton’s post-scan edits—like the photographer’s post-snap edits—work against this “generosity,” so the image conveys, to a higher degree, the author’s intentionality. The photographic image disappears momentarily to some mysterious place between the photo paper’s exposure to light and its bath in a chemical fixer, just as it does between Guyton’s hitting PRINT and waiting for his Epson 9600 to spit out the image. The artist relies on happy (perhaps overdetermined) accident and the confidence of experience while operating in this blind spot: graininess and exposure on the one hand, drips, starts and stops, smears, and misalignments on the other. The image winds itself through a complicated matrix of technological leaps and transfers.

Right: Wade Guyton, Untitled, 2002, felt-tip pen on book page, 11 x 9¼ in. Collection of Candy and Michael Barasch. Image courtesy Scott Rothkopf, Wade Guyton OS, exhibition catalog (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012): 55.

The printer-scanner analogy and the dispersal of the medium emphasize another crucial factor, alluded to above: what Lee Friedlander has called “the generosity of photography.” The camera (or scanner) records whatever is in front of it, whether desired or not. The operator’s inability to control these factors results in a commensurate dispersal of authorship. As Friedlander put it, the camera “records everything it sees, whether you like it or not”:

I only wanted Uncle Vern standing by his new car (a Hudson) on a clear day. I got him and the car. I also got a bit of Aunt Mary’s laundry and Beau Jack, the dog, peeing on the fence, and a row of potted tuberous begonias on the porch and seventy-eight trees and a million pebbles in the driveway and more.[1]

In the face of this “maddening generosity,” the photographer is faced with the choice to snap the photo or not. Doing so validates the photographer’s acceptance of Friedlander’s

“generosity,” or his further resolve that what is captured is worth it—is just as interesting. Either way, the artist is interested in the whole of what is captured; the begonias are just as integral to the image as are the visual components of the main event.

Some of the rarest among Guyton’s oeuvre are the works that show his hand, in the traditional sense of the phrase. These are a small group of drawings of felt-tip pen on ripped out book pages from 2002, and I think they are key to understanding his theoretical practice. In one (Untitled (In the steps of the master)), a black-and-white image of Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House, Guyton has sketched a tiny “X” on one of the windows, careful, despite its miniscule scale, to stay within the confines of its architectural geometry. In another (Untitled), a mid-century interior rife with plants and overstuffed bean bag chairs from the likes of Architectural Digest circa 1955, Guyton has enacted a similar move. A large black “X” in marker covers the entire composition, yet this time Guyton ignores the borders of the image, or the confines posed by the image itself. Instead, the extremities of the dominating black letter spill over into the page’s white margins, in what constitutes a crucial conceptual shift for Guyton. Now, he is leaving the apparatus of the citation intact; he is interested in the whole page; he is operating within the limits of the source in its entirety.

Transferred onto his printer works, this logic looks something like his Untitled Epson UltraChrome inkjet works of 2005 (below). The whole page makes it into the work, complete with pagination, and in reverse, as if accidentally inverted on screen or in the scanning process. And if you missed that cue, Guyton plops a white circle over the image (printers render white as no output—a blank space—here showing bare linen primed with white gesso), forcing the viewer to acknowledge the contrast of the crisp, clean white against the dirty yellow of the book’s faded page. The artist’s updated, twenty-first century invocation of Friedlander’s “generosity” stares us in the face, as it does throughout his oeuvre. Elsewhere, we see the frays and rips in the paper of the dust jacket Guyton scanned for the fiery “U” paintings (Untitled, 2006).

Right: Untitled, 2005, Epson UltraChrome inkjet on linen, 51 x 36 in. Collection of Miyoung Lee and Neil Simpkins. Images courtesy Scott Rothkopf, Wade Guyton OS, exhibition catalog (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012): 68.

All this is not to say that Guyton is a photographer (though in a very literal sense, he is). Rather, I suggest that Guyton reveals his own conceptual practice through making work that addresses the essentially conceptual questions of diverse artistic practices. His work offers up a dialogue that is less about the strictures of medium specificity—i.e., articulating the limits of painting as such—than it is about Guyton’s selective appropriation of the philosophical apparatuses of those media upon which his work draws. In every case he is working within a set of parameters (the length and contours of Breuer’s Cesca chair’s steel frame, or the width of the printer multiplied by two as limit for the width of his canvas paintings, for example), but crucial for his printer works is that these limits are partially determined by the artist, partially determined by technology. Relative to photography, my aim here is to suggest how we would be well served to read Guyton’s work through the various art historical discourses that the work itself invokes, offering, perhaps, one lens through which to understand Guyton’s own assertion that while he makes paintings, he is not a painter.

Thanks for the thoughtful analysis. I came across the name of Guyton while reading about Michael Williams. I didn’t give more than a cursory glance until I came across this (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9MAHzzi94Hs) and this (http://instagram.com/p/llgzlhnzPn/). I am very interested in this line of conceptual art. (Although,) I can only really think of Christopher Wool. Cheers.

[…] On Wade Guyton: “Camera is to scanner as photograph is to printer painting, all its misalignments, spatters, and empty spaces included. For both the camera and the scanner, the medium in question is dispersed. Painting is to paint as photograph is to light, to chemicals, to camera. Guyton’s hand is present in the selection, the framing, the culling, and in on the content of the screen: the juxtapositions, layerings, tonalities, saturations, and enlargements. These latter processes bear striking resemblance to darkroom edits; burn, dodge, superimpose. In this sense, despite the scanner’s proclivity to capture everything it sees, Guyton’s post-scan edits—like the photographer’s post-snap edits—work against this “generosity,” so the image conveys, to a higher degree, the author’s intentionality.” For more from this essay: https://ifacontemporary.wordpress.com/2012/12/31/wade-guyton-x-is-to-y-as/ […]