The words are Robert Rauschenberg’s, stripped-in alongside a photograph of Apollo 11 clearing its launch tower: “NOTHING WILL ALREADY BE THE SAME.” Oriented vertically, the typewritten phrase mimics the upward thrust of the rocket, setting it apart from all else within the composition of the page; it is one of twenty mock-ups of the artist’s never-realized Stoned Moon Book (1969), on loan from the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation. Conflating past and present by altering the idiom’s familiar uttering, Rauschenberg collapses the extraordinary long game of the space race and its attendant technological advancements with the instantaneousness of the liftoff. A presidential promise, made in 1961, is here loaded into the few anticipation-ridden seconds during which millions of Americans held their breath at exactly the same time.

Rauschenberg was one of them. NASA invited him, along with seven other artists, to Cape Canaveral in July 1969 to observe the launch of Apollo 11. Since 1967, Rauschenberg had been working with Los Angeles-based artists’ workshop Gemini G.E.L. (and making prints elsewhere since 1962). His familiarity with the printed medium and relationship with Gemini allowed him to continue that collaboration to produce an impressive suite of prints that reflected upon his experience—he was granted unrestricted access—of NASA’s astronauts, complex machinery, and sprawling facilities for the occasion of the first manned flight to the moon.

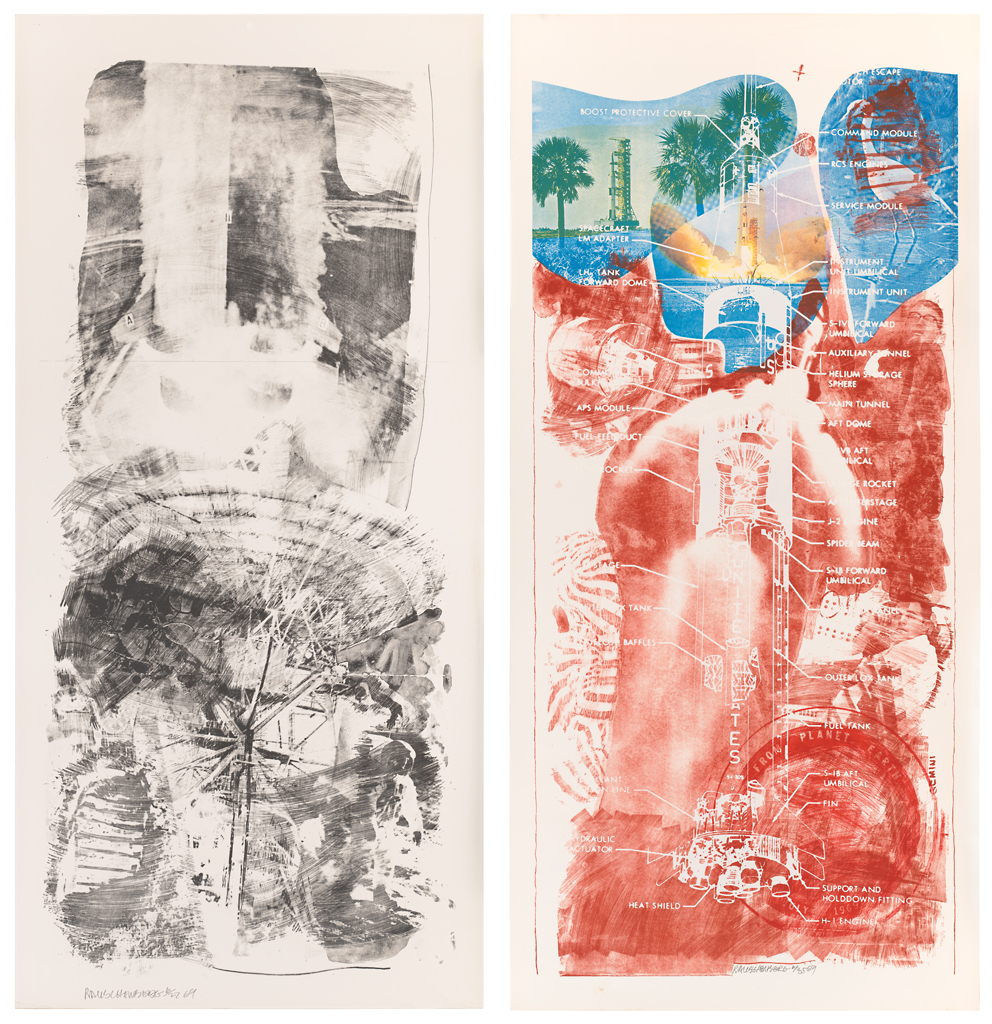

A single-gallery show at the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University, “Loose in Some Real Tropics: Robert Rauschenberg’s ‘Stoned Moon’ Projects, 1969–70” (on view December 20, 2014 through March 16, 2015), exhibits thirteen of the thirty-four lithographs in the series, alongside rarely-seen archival material including photographs of Rauschenberg in the studio, notes he took during his visit to Florida, and twenty of the aforementioned collaged book pages. Taken together, they provide welcome access to the artist’s working process and state of mind. The show benefits from the clear focus of its curator, James Merle Thomas, who enables viewers to hone in on a discrete moment of intersection between artistic production and the shared experience of a monumental historical moment. The lithographs on view, in their varying degrees of abstraction, likewise represent a range of content, intelligibility, and what one could imagine as approximations of onlookers’ sensory impressions. The Stoned Moon works’ relative obscurity makes the Cantor’s a refreshing and gladly received showing, offering an even-keeled selection of the full series’ sensibility and iconography, even if it omits prints in the series that showcase the raw power and dynamism of the liftoff, that snapshot that best conveys the erupting anticipation of the Apollo mission. (It seems, indeed, that excitement was what Rauschenberg was after.) Missed in this regard, then, is a print like Waves (1969), whose vast surface is half-dominated by the enormous force of Saturn 5’s thrusters, surrounded by vapor-like exhaust that Rauschenberg inked in loose, brushy strokes.

Throughout the show, the lithographs—with their layered, multi-colored imagery of state seals, space suits, modules, oranges, smiling astronauts, and egrets in marshy landscapes—evince a Rauschenberg who has worked hard to resist fusing the experience, the implications, and above all, the representation of the Apollo 11 mission into easy distinctions drawn along popular or nationalistic lines. Instead, he retains that complexity by offering up a set of unresolved binaries—unresolved because they were destabilized by the newly-tangible possibility of man on the moon. The immensity (quantified in just about any way: by ambition, financial commitment, the literal size of the rocket or distance to the moon) of the mission exceeded the capacity of photography’s limited scale. Rauschenberg took up the challenge and experimented with size in Sky Garden (1969), one of the best known of the series because it was among the largest hand-printed lithographs at that time. Yet despite the haptic nature of the lithographic process, Rauschenberg recognized the difficulty of closing this chasm and reconciling—visually and conceptually—man’s vastly-expanded domain. Succinctly, he tells us in another collaged page: “CAN’T FEEL BIGNESS ONLY THINK IT.”

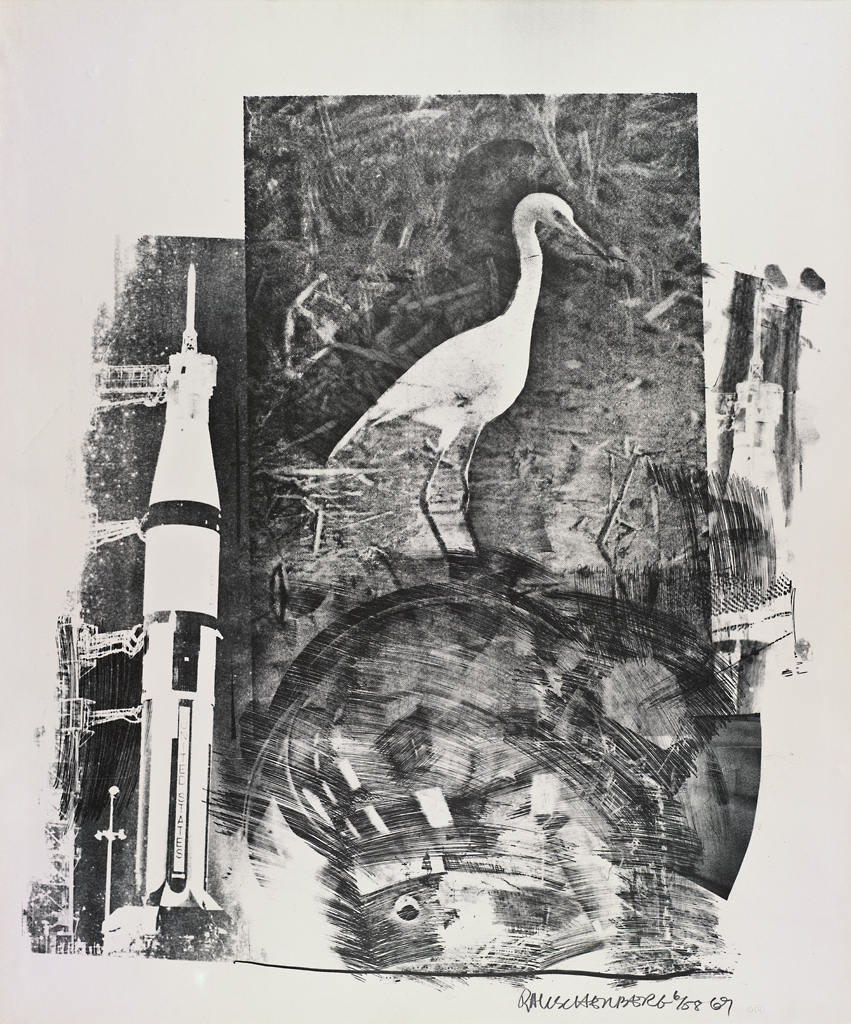

The surfeit of indigenous birds populating the Stoned Moon lithographs speaks to the blurring of the natural and the manmade. Formally, as in Horn (1969), the compositional alignment of herons’ necks with the upright, monochrome rocket shaft suggests the substitution of one flying machine for another. In Trust Zone (1969), Rauschenberg reminds us, via a sepia-tone transfer of the first powered flight at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, of space travel’s precedent not seventy years earlier. (The reference was Neil Armstrong’s, who carried a piece of the Wright brothers’ plane with him into outer space.) Now that humans’ capacity for flight definitively exceeded that of any natural flyer, was nature rendered obsolete?

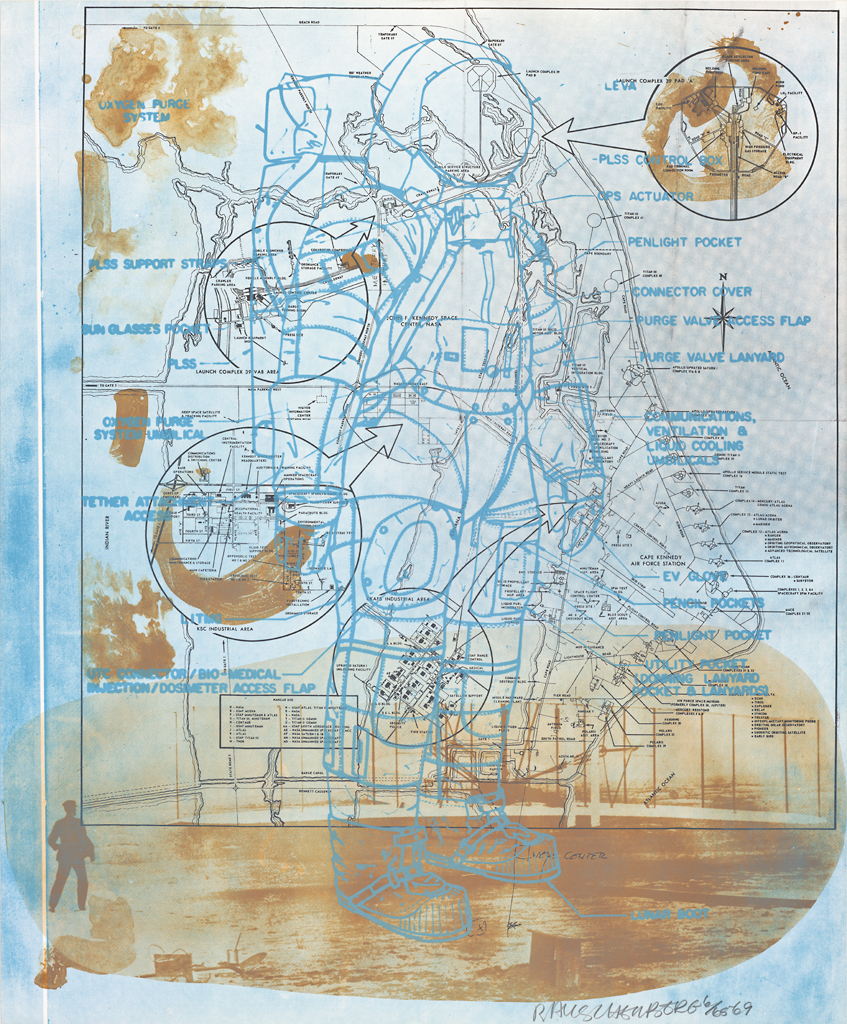

Above Trust Zone’s historic landscape, a schematic rendering of a space suit in periwinkle is superimposed against a map of Cape Canaveral, demonstrating its pedagogical labels’ pertinence to both: oxygen purge system; PLSS control box; connector cover; valve access flap. Tethered to earthly concerns, the terms underscore the stakes of the project at hand and the real threat of a life, extinguished, becoming the province of heaven in tragic exchange of its anticipated, triumphant return to earth. And yet without the space suit, the Cape would fail to signify beyond the terrestrial. One could never transcend it, at least not for the heights (once) considered synonymous with heaven. The bigness of NASA’s manned mission disrupts the neatness of commonly-held binaries between the bodily/earthly and the immaterial/heavenly: Can heaven only exist beyond the reaches of man? Rauschenberg’s own terminology points up that the launch enabled the scrambling of such distinctions:

APOLLO 11 STARTED TO MOVE UP. THEN IT ROSE BEING LIFTED ON LIGHT. STANDING MID-AIR IT BEGAN TO SING HAPPILY LOUD. THEN IN ITS OWN JOY WANTING THE EARTH TO KNOW IT WAS GOING. SATURATED. SUPER-SATURATED AND SOLIDIFIED. AIR WITH A SOUND THAT BECAME YOUR BODY. FOR THAT WHILE EVERYTHING WAS THE SAME MATERIAL. THERE WAS NO INSIDE. NO OUT.

Not only did Apollo 11 confuse boundaries between body and air, inside and out, it also made outer space real in a way it previously had not been by sending astronauts to stand atop and retrieve for later inspection the stuff of the lunar surface. Now, the moon’s materiality was an empirical reality. Rauschenberg drew his own parallel to the popular image of an imprint of Armstrong’s boot on the moonscape by imprinting the event’s historical and cultural reverberations on the litho stone, proving one clever origin of the series’ title. (A moon rock is pictured on the collage intended as the cover page of the Stoned Moon Book.) Conceptually, then, these two stones—lunar and lithographic—align.

Yet in the same passage quoted above, Rauschenberg continued: “POWER OVER POWER JOY PAIN ECSTASY THEN BODILY TRANSCENDING A STATE OF PURE ENERGY. APOLLO 11 WAS AIRBORNE. LIFTING PULLING EVERYONE’S SPIRITS WITH IT.” Bodily transcendence speaks not only to the themes of the divine summarized above, but also to a perceptual disorientation—one that exceeds the bystander’s excitement, anxiety, or stupor. The titular adjective, after all, was not the single “stone,” but something else entirely. In the Stoned Moon lithographs, with their psychedelic barrage of brightly-saturated, piled-high imagery, Rauschenberg affords another reading of Apollo 11’s destabilizing potential. Through a different path than the upset binaries of think/feel, natural/manmade, bodily/immaterial, earthly/heavenly, he is able to situate popular countercultural tendencies alongside the nationalistic, Cold War aims of NASA’s project without overtly addressing either. Stoned Moon, then, indeed, reveals itself a cipher for the multiplicity of ways the very moment of Apollo 11’s launch threw into question the things we thought we knew.

Be First to Comment