The words are Robert Rauschenberg’s, stripped-in alongside a photograph of Apollo 11 clearing its launch tower: “NOTHING WILL ALREADY BE THE SAME.” Oriented vertically, the typewritten phrase mimics the upward thrust of the rocket, setting it apart from all else within the composition of the page; it is one of twenty mock-ups of the artist’s never-realized Stoned Moon Book (1969), on loan from the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation. Conflating past and present by altering the idiom’s familiar uttering, Rauschenberg collapses the extraordinary long game of the space race and its attendant technological advancements with the instantaneousness of the liftoff. A presidential promise, made in 1961, is here loaded into the few anticipation-ridden seconds during which millions of Americans held their breath at exactly the same time.

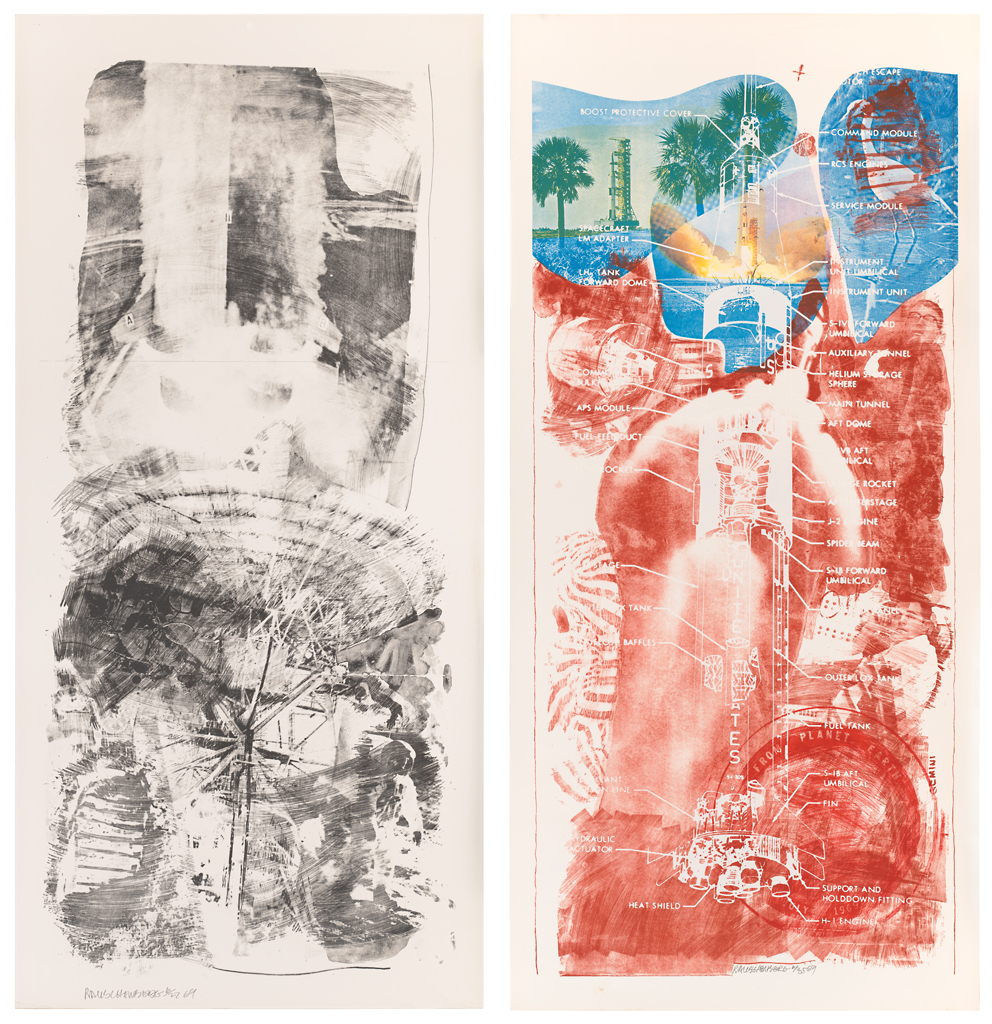

Rauschenberg was one of them. NASA invited him, along with seven other artists, to Cape Canaveral in July 1969 to observe the launch of Apollo 11. Since 1967, Rauschenberg had been working with Los Angeles-based artists’ workshop Gemini G.E.L. (and making prints elsewhere since 1962). His familiarity with the printed medium and relationship with Gemini allowed him to continue that collaboration to produce an impressive suite of prints that reflected upon his experience—he was granted unrestricted access—of NASA’s astronauts, complex machinery, and sprawling facilities for the occasion of the first manned flight to the moon.

A single-gallery show at the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University, “Loose in Some Real Tropics: Robert Rauschenberg’s ‘Stoned Moon’ Projects, 1969–70” (on view December 20, 2014 through March 16, 2015), exhibits thirteen of the thirty-four lithographs in the series, alongside rarely-seen archival material including photographs of Rauschenberg in the studio, notes he took during his visit to Florida, and twenty of the aforementioned collaged book pages. Taken together, they provide welcome access to the artist’s working process and state of mind. The show benefits from the clear focus of its curator, James Merle Thomas, who enables viewers to hone in on a discrete moment of intersection between artistic production and the shared experience of a monumental historical moment. The lithographs on view, in their varying degrees of abstraction, likewise represent a range of content, intelligibility, and what one could imagine as approximations of onlookers’ sensory impressions. The Stoned Moon works’ relative obscurity makes the Cantor’s a refreshing and gladly received showing, offering an even-keeled selection of the full series’ sensibility and iconography, even if it omits prints in the series that showcase the raw power and dynamism of the liftoff, that snapshot that best conveys the erupting anticipation of the Apollo mission. (It seems, indeed, that excitement was what Rauschenberg was after.) Missed in this regard, then, is a print like Waves (1969), whose vast surface is half-dominated by the enormous force of Saturn 5’s thrusters, surrounded by vapor-like exhaust that Rauschenberg inked in loose, brushy strokes.