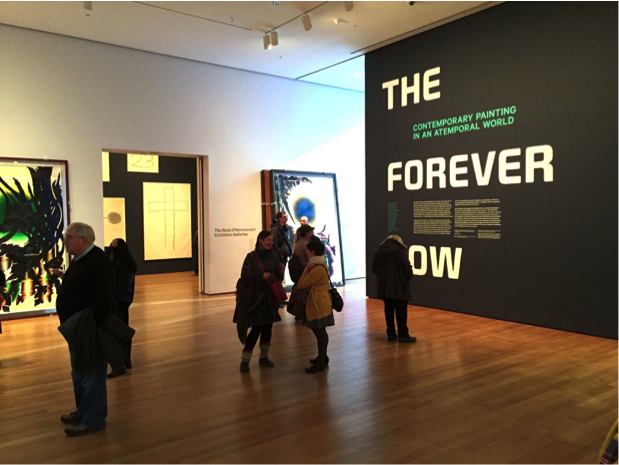

Proclaiming the current cultural moment as one in which all historical eras coexist, The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World (on view December 14, 2014 to April 5, 2015) constitutes the Museum of Modern Art’s first survey of contemporary painting in over thirty years. Occupying half of the museum’s uppermost floor, The Forever Now presents works by seventeen international living artists that is grounded in art historical references but shuns the constraints of art historical chronology. While vibrant and engaging, an exhibition of such stature merits criticism concerning the market-driven nature of much modern-day painting. The show asserts a-temporality as its theoretical basis, appearing first and foremost as MoMA’s unwavering and bold (though risky) attempt to take seriously—and defend—painting when its integrity is severely undermined by the whopping demands of the ever-expanding contemporary art market.

The Forever Now presents painting in the wake of the proliferated image and Internet culture, drawing its thesis from the definition of “a-temporality” (or timelessness) first proposed by science fiction writer William Gibson. In the words of curator Laura Hoptman, the artists represented in the show relieve their art of “modernism’s burden of progress.”[1] The exhibition features predominantly abstract works in diverse media. Striving to present a multitude of inspirations and styles in an a-temporal world, the curators (Hoptman with curatorial assistant Margaret Ewing) provide the viewer an opportunity to experience timeless art in full scale. There are, among other works, Joe Bradley’s crude drawings on canvas, Julie Mehretu’s grey scribble paintings, Oscar Murillo’s colorful patchworks, and Mary Weatherford’s striking neon works. All of them are large, vibrant, and audacious, as if openly making the declaration: painting is alive and well.

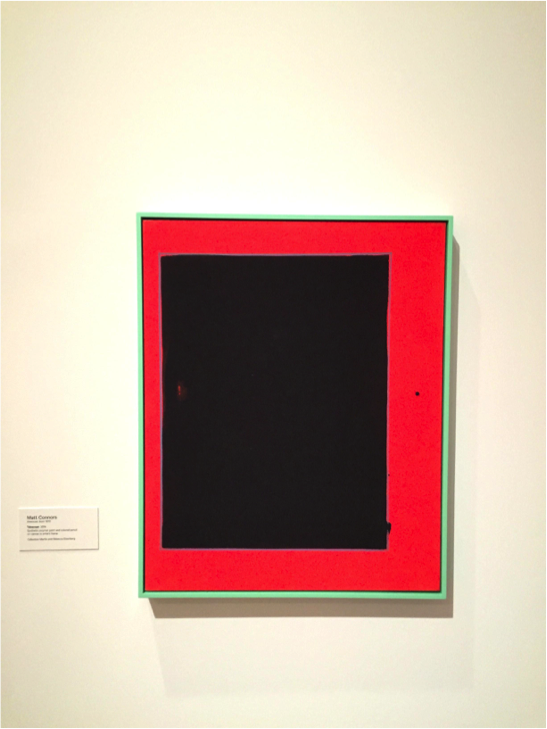

Indeed, a quick stroll through the galleries is likely to intrigue even the skeptic. But as with any show that ventures to declare something new (the paradox here is that to understand the exhibition’s premise, one must, in fact, engage in chronological thinking in order to consider old alongside new), The Forever Now features both a large number of great works as well as some less successful ones. Most of the artists represented are American, and a majority of them are men. Nonetheless, female artists lead the show. Amy Sillman’s oil paintings astound, demonstrating their refined compositions and her remarkable awareness of color. In the catalogue entry on Sillman, Hoptman compares her bold brushwork to the Abstract Expressionist techniques used by Philip Guston and Willem de Kooning. Although Abstract Expressionism is nearly five decades behind us, Sillman’s richly colorful work shows great compositional skills and thus provides a grippingly fresh insight into abstraction. Likewise, Mary Weatherford’s landscape-inspired Flashe and neon paintings mesmerize the viewer. Inspired by the striking contrast the artist observed between privileged and disadvantaged neighborhoods in New York and Los Angeles, these works evoke the bucolic sublimity of the Hudson River School through their reference to the American landscape and combine it with the painterliness of postwar Color Field painting (Morris Louis’s Veils from the late 1950s and Helen Frankenthaler’s abstractions come to mind). Dianna Molzan’s vigorous, three-dimensional works in fabric and wood as well as Matt Connors’ take on Minimalism are similarly engaging. Molzan’s work proves that spatial experiments with abstraction are far from dead, while Connors’ beautifully-crafted monochromes provide a striking example of contemporary investigations in color theory.

The dark abstract pieces by Michaela Eichwald, psychedelic portraits by Nicole Eisenman, and gray Twombly-like scrawls by Julie Mehretu appear emotionally troubling and visually captivating. Also on view are Laura Owens’ paintings, which synthesize figurative forms and sharp colors, as are Oscar Murillo’s works, which bring vibrant colors into the third dimension by allowing viewers to fold and unfold his fabric patchworks. Among the least successful works are those of Joe Bradley and Rashid Johnson. Bradley’s archetypal, Pollock-inspired naïve drawings feel dull. Made with grease pencil on canvas, Bradley’s works appear as a series of unsuccessful attempts to re-invent an early twentieth-century interest in primitivism. It is a shame, because Bradley is capable of attaining much more. Johnson’s black soap and wax works seem oddly incomplete and fail to represent the socially- and politically-oriented efforts of this otherwise provocative African American artist.

The Forever Now not only forces a debate about the significance of painting in today’s world, but also proposes a possible solution. By theorizing a-temporality, the exhibition strives to demonstrate that painting might still be considered culturally relevant and that, at least for a while, one has the ability to disregard the inflated contemporary market. It does its best to circumvent the commercial nature of much modern-day art. By endeavoring to build a solid theoretical grounding for twenty-first century painting, the show does its best not to present the artists as “brands.”[2] “What characterizes our cultural moment at the beginning of this new millennium is the inability — or perhaps the refusal — of a great many of our cultural artifacts to define the times in which we live,” reads the introduction to the exhibition catalogue.[3] Undoubtedly, the Internet has irrevocably changed our perception of and access to art by proliferating images infinitely. For this reason, I am grateful that MoMA makes an attempt, however grandiose its declaration might first appear, to incorporate a-temporal painting into the history of art.

Yet, despite its a-chronological declaration, The Forever Now is strongly grounded in history. The exhibition’s detailed catalogue makes numerous references to the past, looking as far back as Titian. According to Hoptman, a-temporal artists do not replicate or re-appropriate styles, but instead use “signifiers of styles — gestures, languages, and strategies” as motifs.[4] This “art-historical baggage,” as the curator calls it, is pertinent to the artists and artwork featured in The Forever Now. More than ever, artists are culling from a plethora of visual references to create new dialogues with the past, unhindered by chronology. In the catalogue, Hoptman also focuses on the far-ranging issues that arise when tackling a-temporality in contemporary painting. Among them: questions of reanimation, reenactment, nostalgia, and artistic cannibalism characteristic of a world that is identified by a surplus of visual content, each analyzed with reference to art history and art historical theory. Following post-modernism, a-temporality seems, then, to be both saluting the past and welcoming a new era in which cultural and stylistic references are expected to arrive from all possible directions.

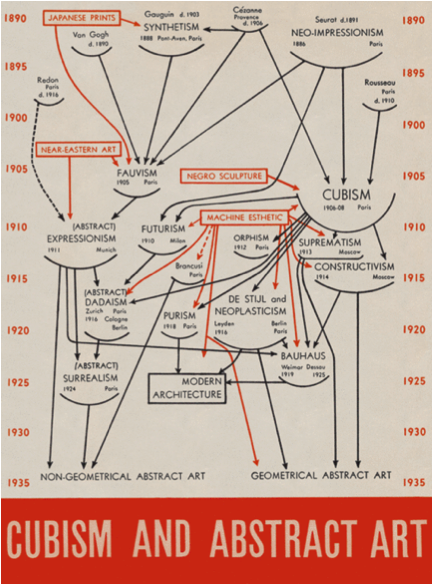

Such a realization illuminates at least one motivation for The Forever Now’s placement in MoMA’s flagship building and not at PS1, the institution’s main outlet for contemporary art. Rather than exist in isolation, the dense web of cultural, stylistic, and, indeed, historical connections seen in The Forever Now are able to resonate with their referents displayed throughout the building. Consequently, the exhibition amounts to more than a mere curatorial examination of the current state of painting, and instead represents a resolutely historical statement made by an institution famous for giving visibility to new developments in the course of modern art (Alfred Barr’s famous “Cubism and Abstract Art” from 1936 is but one example). Perhaps, then, this is just the latest blip on MoMA’s grand, sweeping, teleological narrative. But if The Forever Now insists on timelessness, is it also capable of asserting its place in the history of painting? Although the art on view in The Forever Now — as well as the question of its possible historical significance — has yet to stand the test of time, the exhibition has already succeeded at encouraging the viewer to reconsider the excess and proliferation of images that characterize the age of the Internet, thus identifying an important aspect of modern visual culture. With contemporary painting’s viability at stake (if this exhibition does not defend its integrity, then what will?), the curators’ a-temporal effort appears both risky and commendably courageous.

[1] Laura Hoptman, The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2014), 66.

[2] The term “brand” refers specifically to Don Thompson’s book The $12 Million Stuffed Shark: The Curious Economics of Contemporary Art, in which the author describes how contemporary art galleries effectively publicize their artists and how such publicity efforts might result in “branding” similar to commercial branding of a luxury car manufacturer. See “Branded Dealers” in Don Thompson, The $12 Million Stuffed Shark: The Curious Economics of Contemporary Art (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010).

[3] Ibid., 13.

[4] Ibid., 19.

Be First to Comment