In early February, Curatorial Assistant Ingrid Langston and IFA MA Candidate Ashley McNelis toured the MoMA galleries. Langston assisted MoMA PS1 Curator Peter Eleey in organizing the exhibition Sturtevant: Double Trouble at MoMA, which runs from November 9, 2014 to February 22, 2015. Double Trouble is timely not just in light of the artist’s recent passing, but also because it is only Sturtevant’s second American-organized solo show since the 1970s. The intervening four decades—in which Sturtevant was largely ignored by the art world—have afforded her audience the time and hindsight to catch up with her intelligently penetrating vision. Sturtevant: Double Trouble also juxtaposes traditional art historical narratives (represented by works in MoMA’s permanent collection) against works from Sturtevant’s reactionary oeuvre. The exhibition will be on view in the third floor Special Exhibitions Gallery and the fifth floor Sue and Edgar Wachenheim III Painting and Sculpture Gallery at MoMA until it heads to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles from March 21 to July 27, 2015.

Ashley McNelis: I understand that Sturtevant actively combated the use of curatorial strategies at other institutions. What was working with her at MoMA like?

Ingrid Langston: Unfortunately, I never got to meet her personally. She was working with Peter Eleey closely and was planning to come out for the installation before she passed away in May 2014. Peter went to Paris every few months to meet with her, but by the time I came on the project she was not really traveling much. So I never worked with her directly, which is a shame, but probably also made my life a lot easier. We did work closely with her daughter, Loren, too, who, along with her gallery in Paris, is the executor of the estate and the co-producer of Sturtevant’s video works.

In starting with the long hallway to the exhibition space that we were given, there is a puzzle right off the bat. It can be a challenge to draw people in and to make them understand that there’s an exhibition at the end. One of the very first pieces that Peter and Sturtevant placed was the dog, Finite Infinite (2010). It’s striking, like you’re literally running along with the dog down the hallway to the target at the end [Sturtevant’s Johns Target with Four Faces (study) (1986)]. The dog runs again and again into the wall; it’s endlessly repeating. It sets up the notion of the frustration of progress, related to how her whole project went against the idea of a straight, progressive narrative of art history.

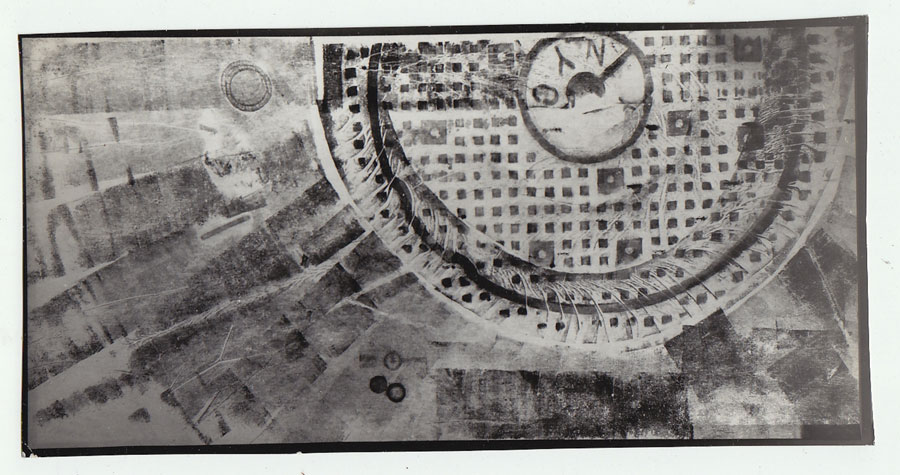

Here, in Study for Muybridge Plate #97: Woman Walking (1966), she strides in front of the lens like in an Eadweard Muybridge, positioned in front of her own versions of Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol, and James Rosenquist. It’s a nod to photography, the most “copying” medium. It’s about action, the circulation of images and the frustration of circular motion like this wallpaper of an owl whose head keeps turning. It’s so weird—we’re pretty sure she just grabbed it off the internet for her 2013 Serpentine show. The exhibition is trying to speak to the consistency of her project. It’s almost shocking how she stuck to her guns pretty much from 1964 when she began recreating the works of other artists.