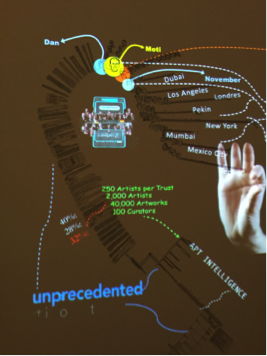

In the first minutes of Walid Raad’s Walkthrough, a performance given throughout the run of his survey show at MoMA, the artist appears approachably nervous. Dressed down in jeans, a black t-shirt and baseball hat, he prefaces his hour-long talk by confessing that he suffers from panic attacks that often lead him to pace back and forth while speaking. Vulnerability suggests sincerity, and the works in this show—full of facts and figures about topical political and cultural issues—support the viewer’s first impression of earnestness. Nearby, an elaborate, colorful tableau visualizing years of research into the history of art in the “Arab world” uncovers connections between the Artist Pension Trust (ATP), a private enterprise offering financial security in the fickle commercial art world, its parent company MutualArt.com, and Israeli military intelligence. All of this data, part of an ongoing project called Scratching on things I could disavow (2007- ) is verifiable, Raad assures us. Yet he says the links revealed are so expected and banal that they are undeserving of an artwork. Oscillating between researcher and artist, Raad not only blurs distinctions between fact and fiction, but also implies that distilling truth from storytelling is entirely beside the point: the real end is engendering a greater awareness of the means by which history is constructed.

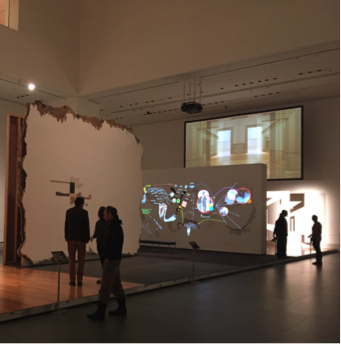

Moving through MoMA’s second-floor atrium as he gradually loses his composure, Raad’s dynamic performance activates many of the issues raised by Scratching …, which makes up half of his first American survey, curated by Eva Respini and Katerina Stathopoulou. Ultimately, however, the performative strategies of this project speak for themselves. The installation is comprised of stage sets where the visitor can experience the art world’s different physical spaces. A parquet floor inspired by the Metropolitan Museum’s period rooms abuts the poured concrete base of a contemporary kunsthalle; the unfinished wall of a Middle Eastern gallery adjoins a pristine white section from the Arab Museum of Modern Art in Doha. Euro-American structures have been imported wholesale to frame regional art at a moment when cultural identity is often defined from without. As his title suggests, Raad has spent the last nine years “scratching” at the interconnections between financial, military, and cultural interests in the Arab world. This institutional critique—simultaneously irreverent and meticulous—brings a new reflexivity to the world’s growing interest in Middle Eastern art in the twenty-first century. MoMA is well-positioned to mount such an exposition as an influential platform for modern art that has, at least thus far, resisted the move among major Western museums like the Guggenheim and Louvre to export its brand into the area.

Raad’s installation foregrounds the consumption of art in present and forthcoming institutions—what art historian Barry Flood, in the exhibition catalogue, calls a “meta-curation.” Unsurprisingly, given its central role in Middle Eastern culture today, Abu Dhabi features prominently in Raad’s environments. Digital and built renderings imagine Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim, which will open next year in Saadiyat (Arabic for “happiness”), an island off Abu Dhabi’s coast housing outposts of several museums and universities (NYU included). For years, Raad has been involved with Gulf Labor, an organization of artists that lobbies for the rights of migrant workers on such Western construction projects. His focus on the region recognizes the paradox that retrograde labor conditions facilitate such cultural progress: the Gulf’s rampant growth in the arts comes at a human cost that the resulting immaculate spaces quite literally whitewash.

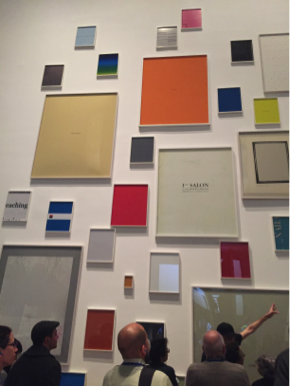

Fetishizing the visual arts transcends the physical realm, also extending to the discourses that develop a canon. Language frames the reception of this art as much as walls and floors do: a misspelled list of artists’ names, which Raad claims to have received telepathically from the future, is inscribed across a gallery wall; a salon-style hanging mixes excerpts of auction catalogues with academic papers intending to offset commercialization with rigorous analysis. Taken in concert with Raad’s architectural platforms, these texts explore the possibilities, and limits, of writing a history of contemporary art in the Middle East—a hot-button task that is as intellectually challenging as it is politically fraught.

Beneath the surface of Raad’s work lies an insistent question: how do we document a living history? In his performance, Raad hints at an answer when he divulges that an ATP founder sought to trademark the words “September 11, 2001” mere hours after the towers fell. Marveling at what he calls this “presence of mind” and “foresight,” Raad draws attention to the financial incentives underlying acts of remembrance, the calculations behind tragedy. Of course it was this very historical event—the terrorist attacks in New York and Washington, D.C. in 2001—that helped expand American interest in the Middle East in the first place, and Raad’s work is in many ways a meditation on the culture industry’s role in moderating the Islamic and Western worlds during a time of heightened political sensitivities.

Alongside the immersive installations housed in MoMA’s atrium, Raad also produces an architectural space in miniature. A model of a gallery in Beirut displays tiny versions of works from The Atlas Group (1998-2004) on view full-scale in MoMA’s third-floor temporary exhibition galleries. These images represent Raad’s best-known project: a fictional archive that documents the Lebanese Civil War as a way of confounding the viewer’s preconceptions about the factuality of the photographic medium. Growing up in Beirut, Raad experienced the trauma of the war firsthand before moving as a teenager to the U.S., where he received his BFA from the Rochester Institute of Technology and his Ph.D. in Visual and Cultural Studies at the University of Rochester. The Atlas Group’s imaginary archive, comprised of photographs and films appropriated from original sources but mediated by Raad’s first-person narratives and the exhibition strategies of conceptual art, recalls Mike Mandel and Larry Sultan’s seminal photo-book Evidence (1977). By intermingling one of their own images with photographs culled from scientific, corporate, and institutional archives, Mandel and Sultan’s book destabilized photography’s informational authority. This outlier was the exception that proved the rule: what could the “real” photographs be said to verify if any of them could merely be a figment of the artistic imagination?

Raad has taken this logic to an extreme by weaving found images into his narratives. The ease of photographic manipulation in the digital era—a new set of technological conditions emerging while the Lebanese Civil War was drawing to a close—further muddles the desire for permanence and stability underwriting the archival impulse. In the exhibition, large close-ups of explosives, for example, are attributed to a woman who used these photographs to help her remember the names of thousands of weapons as part of her assignment in the Lebanese Army. The crudely shot photographs would appear to be useful only for such visual recall. The wall text reveals, however, that they failed to serve their mnemonic purpose and that their maker actually blames the images for her eventual release from the Army. Raad’s story highlights how the photograph and the archive it constructs are poor substitutes for real memory.

Underlining the failure of the archive to serve as a stable cultural repository during periods of crisis, these monumental color enlargements counter the miniature scale of The Atlas Group mock-up gallery downstairs. Raad’s Atlas Group images are either too small to be legible or too large to be useful: both shrink from the task of presenting their contents at anything resembling actual size. Downstairs, Raad recounts an imaginary gallerist who justified the reduced scale of the images by claiming they are more effective when you can’t see them. This glib statement, made by a fictional character driven by commercial interests, is in many ways a fitting epitaph for Raad’s survey as a whole. Perhaps all we can expect of collected information and imagery, whether from the historical archive or the museum, is their actual, material existence as selected traces of significant events. But this is not to diminish the importance of external scaffoldings for collective memory, manifested in various forms in Raad’s provocative displays, which offer a compelling investigation into some of its inherent difficulties.

Be First to Comment