On Kawara—Silence, organized by Guggenheim Senior Curator Jeffrey Weiss with Assistant Curator and IFA PhD Candidate Anne Wheeler (on view February 6 through May 3, 2015), bears the distinct imprint of the artist’s own logic. This is not unexpected given Kawara’s role in determining the exhibition’s structure. Still, following the artist’s death this past summer, viewing Kawara’s work on his own terms is deeply gratifying. Early in the planning process the artist proposed a number of “chapters” or sections that would inform the composition of On Kawara—Silence. Collectively, these chapters include all of Kawara’s artistic production since 1963: notebook sketches known as the Paris—New York Drawings, paintings from the artist’s first years in New York, Code drawings, One Million Years, One Hundred Years Calendars, Pure Consciousness, Journals, as well as the Today, I Got Up, I Went, I Met, and I Am Still Alive series. In the eponymous exhibition catalogue, Weiss explains the genesis of the show’s unique organization: “In choosing these groups of artworks, On Kawara was generously responding to a curatorial proposition: to attempt to represent his practice as a practice rather than assemble a more exclusive selection of individual objects.”[1] In the Guggenheim’s exhibition, hallmarks of Kawara’s practice—repetition and duration—are easily distinguishable, while other connections in and amongst various bodies of work also come to the surface.

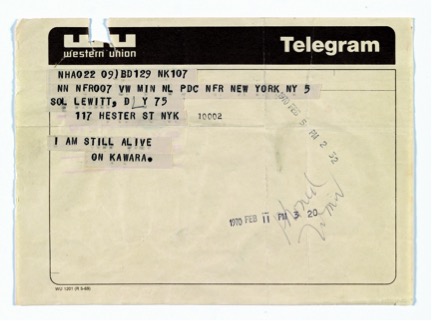

From 1966 until his death in June 2014, Kawara assiduously monitored and recorded his own passage through time and space in serial bodies of work, each of which was developed over the course of a number of years. Collectively, Kawara’s work accounts for time in various units: minutes, hours, days, years, centuries, and millennia. The legibility of Kawara’s chronicling activity is reliant upon the repetition of certain activities (mailing, listing, telegramming, painting) according to the self-imposed restrictions and conditions that limited the production of each distinct body of work: a Date Painting had to be completed within the span of twenty-four hours, the maps comprising I Went charted the artist’s movement in a given day, and each page included in One Million Years contained five hundred years typed into a grid formed by rows and columns.

On January 4, 1966 Kawara coated a small canvas in blue acrylic paint. That same day he brushed white paint in the form of “Jan. 4, 1966” in the center of the blue surface. Inscribing red, blue, and dark gray canvases with the current date was an act Kawara repeated thousands of times over the course of forty-eight years. The complete process involved hand mixing paint colors, applying several layers of ground, penciling the outline of the inscription onto the center of the monochrome canvas (aided by a ruler, but carried out sans stencil), and filling the outlined letters and numerals with white acrylic. Sometimes he repeated this process, creating up to three canvases in one day. In each painting the language and abbreviation of the inscription bears the customs of the country in which Kawara found himself when he produced the work (he executed the inscription in Esperanto when in a country with a non-Roman alphabet). Through this rigorously structured practice, initiated in 1966 and refined throughout his lifetime, he produced paintings linked to the exact time and place in which they were made. However, it is precisely in the neatness and consistency of the Today series that a fundamental paradox exists. Like many of his contemporaries, Kawara eschewed a positivist understanding of time and stylistic progress. As unrelentingly as the Date Paintings record time’s chronological advance, the formulaic production of the series fought against stylistic evolution.[2]

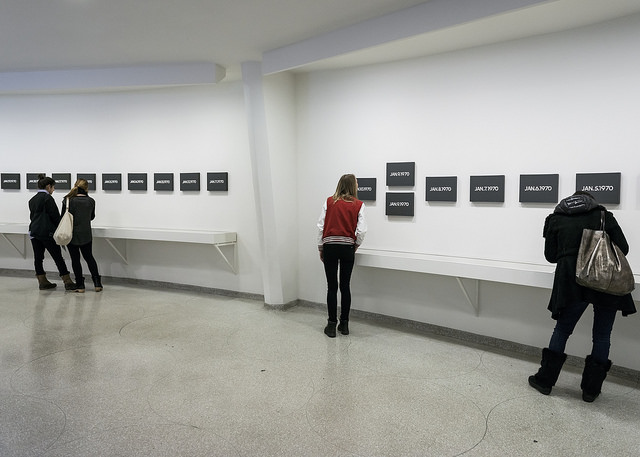

In the Guggenheim show, the chapters defined by Kawara, executed by Weiss, and listed at the start of the exhibition vary greatly in size and scope. Some sections consist of single works, and others such as Journals, I Read, Codes, and One Million Years represent the work or series for which they are named. Other chapters such as Everyday Meditation, Self-Observation: 12 Years, and 48 Years focus on different sets of parameters internalized within specific bodies of work. For instance, Everyday Meditation includes only some of the Date Paintings featured in the exhibition. The ninety-seven paintings included in this chapter were produced daily over the course of three months in 1970. Highlighting an astonishing and singularly intense period of production in Kawara’s oeuvre, Everyday Meditation also invites viewers to consider the day as a unit of time, which is part of a continuous progression of days/time. 48 Years, another chapter comprised of Date Paintings, features canvases in varying shades of red, blue, and gray and includes one painting from every year Kawara worked on the series. Framed in this context, the Date Paintings stand in for a longer temporal period—each canvas acting as synecdoche for the year in which it was created.

In the first tower gallery off the rotunda, the exhibition’s earliest works are grouped according to the following chapters: Paris—New York Drawings, Title, and Location. Also on view in this space is Kawara’s first Date Painting. Shown in a cluster, the Paris—New York Drawings (1964) include a variety of notebook sketches for future works (most of which were not executed, and none of which exist today). In the selections on view Kawara vacillates between the figurative—which defined the Surrealist works he produced while in Japan—and a growing interest in language, mapping, and communication that would dominate his later practice. In 1965 Kawara painted coded and English language inscriptions onto variously sized and colored monochrome canvases. In the gallery, the two extant paintings from 1965 (Kawara destroyed the others), Title and Language, form a discourse with the Paris—New York Drawings and further expand our view of the formative pre-Date Painting period. The installation of Kawara’s prescient early works alongside the prototypical Date Painting in this unique space—simultaneously separate and connected to the rotunda— forms an effective and instructive prelude to the bulk of the exhibition, which wraps around the museum’s spiraling exhibition space.

The ninety-seven 10 x 13 inch dark gray canvases and handmade storage boxes comprising Everyday Meditation are displayed in chronological order in the curved bays just outside of the tower gallery. Along with the exhibition’s final chapter, 48 Years—installed at the top of the exhibition space in reverse chronological order—Everyday Meditation serves as a sort of bracketing device. In other words, the beholder’s journey up the rotunda ends close to where it began: the first canvas in Everyday Meditation was created on January 1, 1970, while the last 48 Years canvas on view dates to 1966. Along our trek back to the beginning (1966), Weiss highlights the stunning dearth of stylistic development that defines the Today series, while simultaneously revealing correspondences within Kawara’s lifelong oeuvre.

Between Everyday Meditation and 48 Years one finds the full breadth of the artist’s production. In this expertly organized middle ground, the logic of each chapter is distinct but conversant with the show’s other component parts. Moving through Self Observation: 12 Years, Journals, I Read, Monologue, Moon Landing, Pure Consciousness, 20th and 21st Centuries, and One Million Years, viewers weave in and out of each section’s distinct chronology. The postcards, maps, and lists included in Self-Observation: 12 Years are relics of the artist’s daily life, which bring us close to a personal timeline of events that unfolded in the recent past. However, in spite of the plentitude of these materials, the artist and his experiences remain elusive.

Further up the ramp, Kawara’s mingling of time and form occurs on a different scale, and is contained in twenty-four black leather binders. Neatly typed on the pages comprising the series One Million Years (1970–1988) are lists of one million years in the past and one million in the future: each binder contains two hundred pages. Examining vast stretches of time—unfathomable on a human scale—as banal sequences of typed numbers, and imagining the quantity of distant millennia encompassed in each of the closed binders, Kawara renders time abstract in both form and concept. The separation of the typed numbers from historical reference and meaning is reinforced by the entrancing live reading of One Million Years (every Sunday, Wednesday, and Friday from 11am to 5pm), in which the typed dates are read alternately by one female and one male volunteer. As the viewer progress through the exhibition, the utterance of distant dates fades into white noise—sound disemboweled of meaning through repetition.

The emphasis of each chapter’s discrete chronology is particularly effective in the rotunda galleries, which possess their own temporal character. Following the natural upward trajectory of the ramp, museum visitors move forward through time as they move forward through space. The interaction of this fluid relationship between space and time with the distinct chronologies of the exhibition’s many chapters invoke us to see the dense network of operations at play in and among the serial bodies of work comprising Kawara’s oeuvre. Moving through the Guggenheim’s installation of Kawara’s work is an odyssey in and out of time—one that echoes the artist’s own mindful and constant observation of his own mutable position in time.

[1] Jeffrey Weiss, “Introduction,” in On Kawara—Silence, Jeffrey Weiss (New York: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2015), 19.

[2] Ibid, 29–30.

Be First to Comment