Like the three fantastic realms of the afterlife in Dante’s Divine Comedy, the New Museum’s current exhibition, Chris Ofili: Night and Day (on view until January 25, 2015), is divided into three distinctly different gallery spaces that challenge viewers to interact with each work in intensely visual, meditative, and thought-provoking ways. The retrospective traces Ofili’s trajectory as a painter over the past two decades, demonstrating his development as an artist who masterfully creates technically complex compositions to address ideas of black culture, female stereotypes, and history. Via the use of controlled environments, curators Massimiliano Gioni, Gary Carrion-Murayari, and Margot Norton have proven that the impact of a work of art is often determined by the setting in which it is displayed.

This isn’t the first time Ofili’s work has been exhibited in New York City. Much to then-Mayor Rudolph Giuliani’s outrage, Ofili’s The Holy Virgin Mary (1996) was displayed at the Brooklyn Museum of Art in 1999 as part of Charles Saatchi’s exhibition Sensation. The former mayor, who called Ofili’s work “sick,” wasn’t alone in his protest; many visitors were deeply offended by Ofili’s daring representation of the Virgin Mary, whose right breast is formed of the now-infamous elephant dung and whose body is surrounded by magazine clippings of female buttocks. In his ire, Dennis Heiner, a seventy-two-year old Catholic Brooklynite, vandalized the work by smearing white paint over it. Fifteen years later, in his first major solo museum exhibition in the United States, Ofili proves that rather than hinder his artistic career, the controversy helped to establish him as one of the most provocative artists of his day.

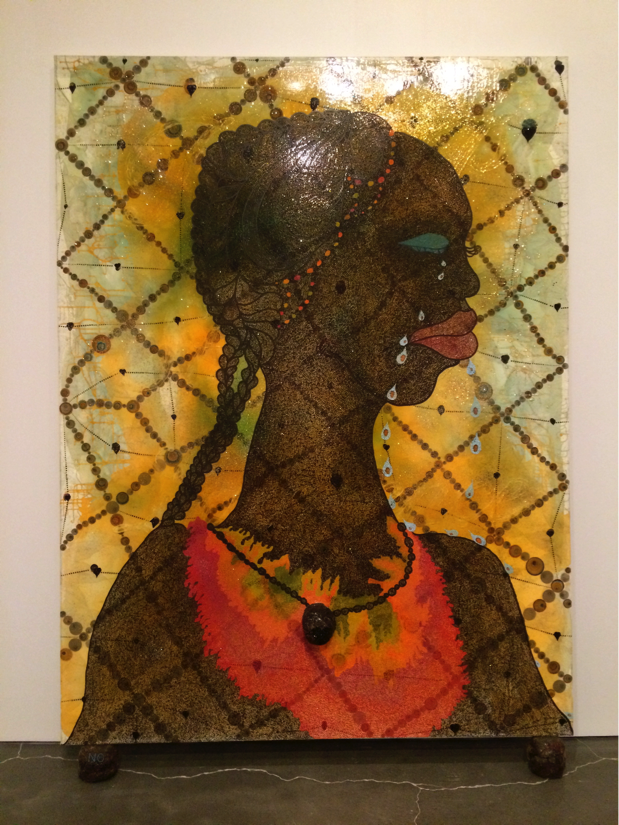

Night and Day occupies floors two, three, and four of the New Museum – nearly the entire building. Organized chronologically, the exhibition begins on the second floor and presents some of Ofili’s most eccentric (as the titles suggest) canvases from the early nineties, including Afronirvana, Pimpin’ Ain’t Easy, Monkey Magic — Sex, Money, and Drugs, and the fully restored The Holy Virgin Mary. Depictions of some of Ofili’s idols, both real and fictional – like the imaginary superhero, Captain Shit – star in these paintings. Here, the more conventional galleries (brightly lit with white walls and sleek polished concrete flooring) are challenged by the intensity of Ofili’s subject matter and media. His paintings are densely layered with brilliant pigments, paper collage, polyester resin, magazine cutouts, glitter, and perhaps his most notorious medium, elephant dung (he first started using the material in Zimbabwe in 1992).

The wild colors and psychedelic patterns of his compositions – inspired by sources as diverse as hip-hop music, the Bible, and Zimbabwean cave paintings – lend the space a lively quality that leans toward happy, even celebratory. But the connotation is misleading. For example, the use of radiant reds, pinks, and gold tones in No Woman, No Cry (1998) belie its poignancy. The painting refers to Doreen Lawrence, the mother of Stephen Lawrence, a teenager who was stabbed to death in London in 1993 and whose murderers were never convicted. She mourns the unjust loss of her son with head elegantly held high; the tears she cries are comprised of pictures of her son, indicating the emotional weight of each drop.

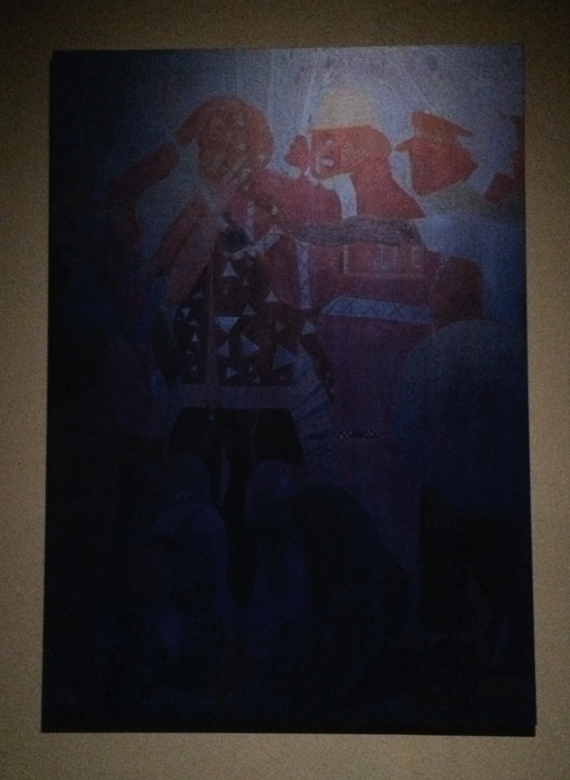

Disorienting. Such is the transition to the third floor of Night and Day. Emerging from neon and glitter, the visitor requires a moment to acclimate to unexpected submersion in darkness. As one’s eyes adjust, nine canvases from Ofili’s The Blue Rider series (2005-2006) slowly materialize on the walls of a dimly-lit room that once again reflects the nature of the works it houses. This time, the artist designed the environment himself. Eight grey walls, a padded grey carpet, and low lighting create a tranquil, meditative setting. Significantly, the octagonal architecture of the space, which recalls the Rothko Chapel, allows for viewers to better see the deep blue hues, hidden forms, and flattened picture planes unique to The Blue Rider paintings.

In this selection of canvases, Ofili abandons the sparkles, excrement, and kaleidoscopic surface patterns that transfixed the visitor on the previous floor. Here, using only silver and blue paint (later adding shades of purple, indigo, and black) Ofili creates scenes and characters that are difficult to parse. Lighting plays a crucial role in the visitor’s understanding of these works; too much causes the paintings to look like over-exposed negatives, but as exhibited at the New Museum, the lighting—or lack thereof—allows the viewer to be lost in a nocturnal sea of blue, black, red, indigo, and even green. As she focuses more intently on the scene before her, she delves deeper into Ofili’s historical imagination. Once the silhouettes emerge, the potency of Ofili’s subject matter begins to register.

In Blue Devils (2014), Ofili depicts a young black man wearing a hooded sweatshirt as he is stopped and searched by police officers in blue uniforms. The artist draws inspiration from the old pre-Lenten rite of Trinidadian carnivals in which men cover themselves with blue paint in order to play the devil and terrorize townspeople. By linking the blue “devils” to the blue uniforms of the British officers the artist makes a powerful (and timely) statement on the historically-contentious relationship between black men and the police. Ofili masterfully elicits increasing horror in the viewer as she falls ever further into the paintings and struggles to come to terms with the (his)tories they tell.

Despite the sudden immersion into the umbra of Ofili’s inky hues in his dimly-lit, meditative-until-shocking third floor gallery, it isn’t until the beholder ventures to the fourth floor that the full extent of the show’s curatorial scenography is realized. Between floors, the museum’s architecture augments the visitor’s anticipation of reaching the final phase of the show. A long, narrow stairway transports the visitor from the darkness still upward to the dazzling spectacle that awaits her on the fourth. Ascending toward the purple calico walls, she is fazed by the vague sensation of slipping into a dream.

The installation is spellbinding. Ofili’s artistic capacities explode across a group of canvases that demonstrates his familiarity with and obvious affinity for the great masters of painting, namely Paul Gauguin and Henri Matisse. The artworks are mounted on walls adorned with tropical foliage in varying hues of purple and lavender. Executed by Scenic Art Studios, Inc., this is a far cry from the sterile white cubes of most contemporary art galleries. The beautifully painted backdrop enraptures the viewer without detracting from Ofili’s canvases. On the contrary, the opulent ornamentation seems to complement Ofili’s work, enticing the viewer to engage more closely with the bright colors, elongated Matisse-like figures, and Art Deco-inspired backgrounds that characterize the compositions. Between the fantastical-yet-naturalistic painted walls and Ofili’s own bold colors, the gallery feels ethereal. It is fitting, given that some of the works were inspired by Ovid’s Metamorphoses and portray mythological scenes of gods and humans, such as Ovid-Actaeon (2011-2012).

The experience is akin to journeying through Dante’s realms; the carefully designed environments of each gallery reflect the stories and figures captured in the paintings that line the walls. The viewer is made to withstand startling transitions from one noticeably-different space to the next. Changes in lighting and architecture heighten the visitor’s awareness of her surroundings, and rhyme with aesthetic and thematic shifts in Ofili’s practice. Rather than take away from the visitor’s appreciation of Ofili’s highly orchestrated compositions, the controlled environments foster emotional and visceral connections to individual works. The use of such purpose-built settings is not only successful, but it is also necessary. Over the past two decades Ofili has created compositions as dissimilar to one another as, well, night and day. Simultaneously displaying these contrasting works – which vary in subject matter, technique, and most obviously, aesthetic – was jeopardous. The curatorial team at the New Museum met the challenge of presenting the disjointed phases of Ofili’s diverse body of work in a unified way. With Night and Day the curators have allowed viewers not only to trace, but more importantly, to experience the variegation of Ofili’s oeuvre.

Be First to Comment