Resident Evil, Sondra Perry’s first solo institutional exhibition, fills the second-floor gallery of The Kitchen with a handful of video works made in the past year. Each is “immersive” in one way or another, deploying tactics of spatial activation and coercive, embodied viewing to force visitors into visceral engagement with the screens and their troubling content. These strategies of discord and discomfort mirror the works themselves, which center themes of police brutality and other racialized violence, examining how images and narratives of these issues circulate, distort, and abstract in the digital realm.

The first work one encounters in the exhibition is netherrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr 1.0.3 (2016), set into its own tiny black box. In the video, Perry draws a provocative parallel between the “blue screen of death”—the infamous error screen in Windows operating systems—and the “blue wall of silence,” an unwritten oath among police officers not to incriminate one another in cases of excessive force, brutality, or even murder. At one point in the video, footage of Bill Gates and other Microsoft executives dancing on a convention stage is dubbed over with a deadpan, computerized description of the unwritten officer’s code of conduct (perhaps a double entendre with the computer code that later scrolls by). Another passage features images of women killed by police set to the same voice describing the blue error screens in banal terms. Though intentionally ambiguous, the video uses montage to suggest that capitalist systems and their technological agents are intimately connected with, if not responsible for, the violence wrought against black bodies in neoliberal America.

Having established the color as anything but neutral, Perry has had every wall in the remaining gallery space painted the same hue of royal blue from this video. The effect is claustrophobic and profoundly disorienting.

Inside the main gallery space, two video works are installed on exercise machines such that viewers must mount the apparatuses and put on enormous headphones to experience them fully. Graft and Ash for a Three Monitor Workstation (2016) comprises three screens atop a stationary bicycle. At close range, viewers are greeted by a digitized avatar based on Perry’s face, who hovers on the monitor and describes the various ways in which being black in America taxes the body. The almost-but-not-quite-human character is disturbing, joining us straight from Freud’s Uncanny Valley. “Just being who we are is extremely risky,” she says.

There’s a biting, dark humor to many of the pseudo-Perry’s statements. “We are not as helpful or Caucasian as we sound,” she informs at one point. “We have no safe mode.” The video is set to a lush soundtrack of soothing synth tones that gradually soar to a climax. The effect is intensely contradictory and discordant, at least for the white viewer faced with the brutal reality of daily life for black Americans in a police state, communicated by a soothing, self-help robot guru. The labor invoked by the exercise machine suggests that white people (presumably most of The Kitchen’s audience) must put in physical work to truly understand and begin to dismantle these oppressive racist systems.

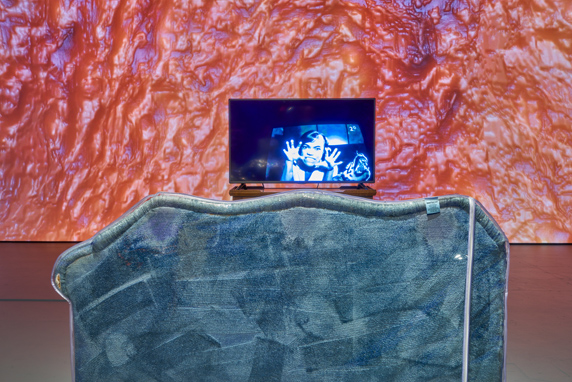

The centerpiece of the exhibition is Historic Jamestowne: Share in the Discovery and Take Several Seats (2016), an installation that recreates a classic suburban living room mise-en-scène. A television set plays from atop a credenza, while viewers watch from an ugly, vinyl-covered sofa. The video itself includes footage of the Baltimore demonstrations in the wake of Freddie Gray’s death in the back of a police van, shot both from an on-the-ground protester’s cellphone and Fox News cameras; audio of a Democracy Now interview with Ramsey Orta, the man who filmed Eric Garner’s death; and low-res footage shot inside a drab interior not unlike the one in which the video work itself is viewed. Viewers are coerced to “take a seat” and watch the difficult montage—a literalization of the phrase often used to direct white people, especially well-meaning ones, in conversations surrounding anti-black violence that should foreground the voices of those most affected by it.

Behind the TV, a large projection fills the entire far wall of the gallery. Titled Resident Evil (2016), its distorted, undulating imagery was created with close-up footage of Perry’s skin. It is grotesque, engulfing the space in a biomorphic, oozy substance. The work is Perry’s most literal exploration of the interaction between technology and blackness. As the Resident Evil of both the work’s and exhibition’s titles suggests, Perry seems to present this visceral, amorphous substance as a virus that could infect all of the white supremacist technocratic systems on display in the exhibition. Black can be beautiful, but it can also be nasty; it can be weaponized against the systems that devalue it. As a vampy Earth Kitt sings in I Wanna Be Evil—a clip of which has made its way into Historic Jamestowne—perhaps the only way to fight these evil systems is with evil itself. To hell with respectability politics.

Perry’s brilliant companion publication to the exhibition is distributed to gallery-goers by an animate Roomba vacuum cleaner. It ends with a passage from a 1971 speech by Sun Ra. “I can’t go around telling you I’m right or good when the dictionary is telling everyone around the world that everything black is evil and wicked,” he says. “So then I come and say yes, so what? Yes I’m wicked. Yes I’m evil. I’m not going to be converted. I’m not going to subscribe to righteousness… Good folks don’t ever do nothin’ but be good, and they always failin’, and they always getting killed, and they frustrated.”

Editor’s Note: Sondra Perry: Resident Evil at The Kitchen closed on December 10, 2016.

Be First to Comment