Selfie stick: in hand. Move through the museum; photograph any object that piques one’s interest; apply filter; glance at wall labels if conveniently nearby. Some artworks become sites for group portraits while others—contours carefully (or not) framed within the familiar rectangle of the iPhone screen—warrant a photograph of their own. Lack of discrimination is fine: 16GB of storage can surely hold this many digital files. Move on.

The experience is a familiar one, one certainly known, if not first hand, through inadvertent observation. The facility of digital photography, via the ever-present smartphone, has accelerated the act of looking in the museum. The discourse around this phenomenon is often presented in negative terms, terms frequently indebted to Walter Benjamin’s essay on mechanical reproduction, terms which remind us to be self-critical about the cultural baggage of outmoded concepts like the “original” or “authentic,” and to consider carefully the status of the replica.

The medium of painting, sitting comfortably atop the hierarchy of artistic production, is an obvious lodestone and conceptual linchpin here. To take a single work as an example, artist Ken Okiishi’s commission for Frieze Projects London in 2013—a Perspex walled space with windows on all sides containing visitor-activated paintball guns spewing fuchsia and saffron orbs—was conceived to function both in temporary installation as well as in endless proliferation on the web, as representation. As Okiishi put it:

On a technical as well as on a formal level, it’s a piece that is designed to be photographed, posted and reposted rapidly and with great enthusiasm […] These explosions and smears and drips that happen will become very desirable to be photographed, to be videoed, to be sent on Instagram or Vine or whatever.

As two poles of a conceptual spectrum (unique site of creativity on the one hand; ultimate proliferator on the other), painting and the screen become, paradoxically, easy bedfellows. In the Frieze installation, paint splats multiply across transparent windows and layer atop those on the walls behind; the screen of a smartphone creates yet another layer. Meaning is both lost and gained. Click and run.

This summer, two museum shows grapple more broadly with the implications of repetition, the archive, and digital technologies of replication. The Jewish Museum’s Repetition and Difference (on view through August 16, 2015) and the Utah Museum of Fine Arts’ salt 11: Duane Linklater (on view through August 2, 2015), open up for questioning, from two different angles, the ontology of the museum object vis-à-vis artistic techniques of replication, whether eighth-century BCE or contemporary, analog or digital. Most striking is the extent to which both shows welcome the issue of replication—understood as both material process and conceptual construct—as an opportunity to be transparent and self-critical about aesthetic assumptions, colonial influences, and, ultimately, collecting biases. Said differently, repetition, sameness, difference, and authorship are bared as the gatekeeper’s invisible hands.

In four galleries at the Jewish Museum curated by Susan L. Braunstein and Jens Hoffmann, historic, ritual objects sit alongside contemporary works. Ancient fertility figurines juxtaposed against bronze casts of cheap polystyrene mannequin heads, for example, prompt questions about individuality, uniqueness, and intransience. Elsewhere, vast stylistic divarication of dozens of gold and silver spice containers, with dates spanning a hundred and fifty years, attest to the prototype’s status as concept rather than physical model. Each one’s components—leaves, stem, filigreed fruit, with an animal atop (here an eagle, there a squirrel)—are only nominally alike; in form, contour, and pattern, they demonstrate delightful variation. Acting as a foil to the artisanal imitation of the spice container’s conceptual ideal are a series of Polish and Ukrainian menorahs from the eighteenth through the twentieth centuries. Taken from the Jewish Museum’s permanent collection, some of these Hanukkah lamps, many comprised of the same motif, are direct ancestors of others on display. Acquiring dings and losses through years of use, a well-loved menorah might then be used to cast new models, which in turn retain the flaws of its parent. Here, we confront preconceptions about aesthetics over function, high over low.

c. 1800–1939. Silver and gold. The Jewish Museum, New York. Gifts of Dr. Harry G. Friedman and Mr. and Mrs. Albert A. List; the Rose and Benjamin Mintz Collection. Image courtesy the Jewish Museum.

In Salt Lake City, the Utah Museum of Fine Arts invited artist Duane Linklater as the eleventh participant in its salt exhibition series, which features work by international emerging artists. Linklater, who is Omaskêko Cree from Moose Cree First Nation in Ontario, Canada, selected eight three-dimensional and nine two-dimensional ethnographic artworks from the museum’s permanent collection for replication through digital technology. Clay pots, masks and headdresses, totem poles, and a kachina doll—all with unknown makers—were scanned and 3D printed in collaboration with University of Utah library’s 3D printing facility; images of textiles Linklater selected remotely from the museum’s collections database were printed on linen.

Both processes reveal the limits of technology. Linklater never saw the Museum’s textile works; instead of using an extant, high-resolution file, he exploited the weaknesses of digital technology by photographing an image of the work as it appeared on his computer screen. Forced through a series of cyber transfers, the image is degraded, and information—resolution, saturation, scale, orientation—is lost. The textiles are literally flattened, losing the peaks and valleys of warp and weft while gaining moiré-pattern optical illusions. Such distortions are byproducts of the photographic process; they are not present in the ethnographic object. The reproduced sculptures, 3D printed in milky-white plastic, are drained of color. Due to the imperfect translation of pixelated data through technological leaps, they are bumpy—materially built-up—where the prototype wasn’t, and seams attest to their very different modes of production.

Though salt 11: Duane Linklater comprises only one gallery, it packs a big punch, not least because some of the objects that inspired Linklater’s project are on view in an adjacent gallery, such as a Navajo or Diné Chief’s blanket. As curator Whitney Tassie—who admits she was “a little apprehensive” about opening the museum to criticism—notes in her smart catalogue essay, the artist’s “copying process physically expresses the loss of information that occurs as American Indian objects transform into Westernized ethnographic objects.” Linklater makes visible this complex and often invisible process, drawing attention to the museum’s history of power relations, its colonial legacy, and its collecting biases. As philosopher Roland Barthes put it in 1963,

…to reconstruct an “object” [is] to manifest thereby the rules of functioning (the “functions”) of this object. Structure is therefore actually a simulacrum of the object, but a directed, interested simulacrum, since the imitated object makes something appear which remained invisible, or if one prefers, unintelligible in the natural object.

Linklater’s process of reconstruction, repetition, or replication produces a second physical object alongside the first. This not only forces consideration about the museum’s past archival choices (and all the obscured motivations therein), but also—inevitably, by comparison—about the museum’s contemporary collecting practices. Will Linklater’s 3D sculptures, credited as courtesy of the artist and Catriona Jeffries Gallery, be acquired by the Utah Museum of Fine Arts? (If not, why? How would they signify in a different museum collection, prized from proximity to their sources? Would this reenact, on another level, the initial loss of context endured by the ethnographic objects when they entered the museum in the first place?) At stake is the ontology of the object in the wake of digitization’s ongoing collapse between things and information. These are matters of classification (is it a work of fine art, a facsimile, a reprint?) and quantity (can more be printed on demand, and if so, how many and under what conditions?). Asking these fundamental questions about the status of the artwork brings us to the heart of the museum’s function and the subjective collecting decisions it makes. Inviting the practice of replication into its living room, the museum can’t help but be frank with visitors about navigating these issues.

Bottom: Duane Linklater, UMFA981.016.002, 2015. 3D-printed sculpture. Courtesy of the artist and Catriona Jeffries Gallery. Image courtesy Utah Museum of Fine Arts.

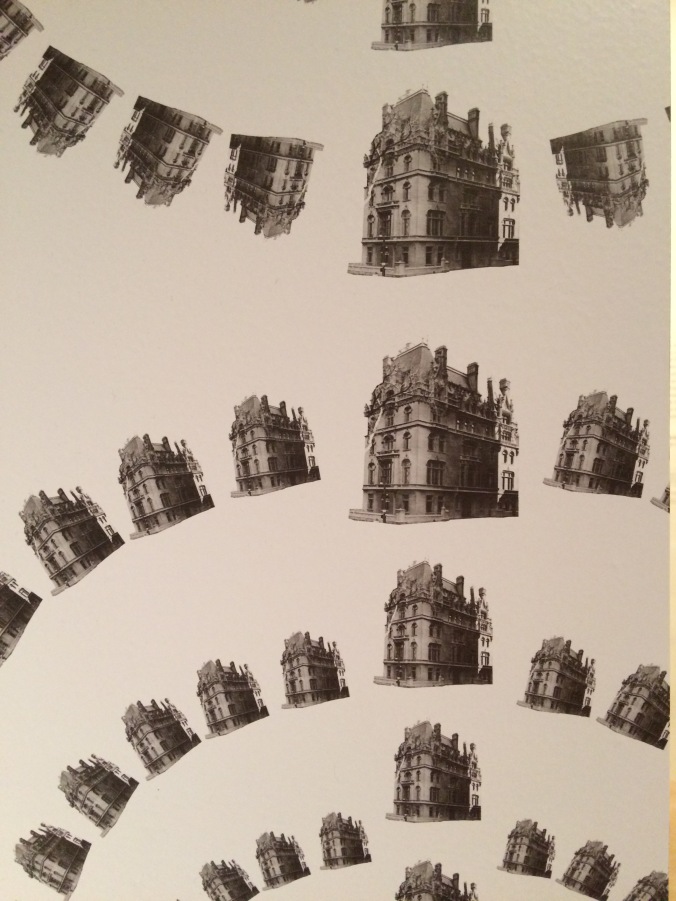

This is true at the Jewish Museum, too. Despite the fascinating and conceptually-thorny questions its ritual objects invite, the show’s real revelation came tucked in an unexpected corner. There, an inconspicuous label, unadorned and not proximate to any artwork, relays the logic of a bespoke wallpaper created for the exhibition. Hung so high in each gallery of Repetition and Difference so as to be nearly impossible to see, the wallpaper, the label tells us, depicts miniature photographs of the Jewish Museum’s Warburg House at different moments in its history. The text continues:

These wallpapers evoke the way pictures circulate in reproduction, and point toward the concept of the museum as a repository of art and culture. Culture itself is an archive: humans collect objects that (we think) have taken art and ideas to new places, artistically and intellectually, aesthetically and politically. Our process relies on the principal [sic] of difference and repetition: we affirm what came before and we deviate from it. When we affirm too much we are conservative; when we deviate too much we are radical. The museum is a collection of objects that represents this process of affirmation and deviation.

The museum is not exempt from this critical investigation of repetition. By papering its own walls with images of itself, the Jewish Museum not only acknowledges its role as place of inquiry, but also subjects itself to the same conceptual scrutiny as any other object in the exhibition. A glimmer of institutional self-criticality among a slew of otherwise clever scenographic or design choices—reflective surfaces adorn gallery passageways, signage indicates “Exhibition repeats” (rather than continues)—this moment of transparency underscores that the intellectual pursuit of repetition, which permeates so many aspects of our lives, cannot be contained to the aesthetic or art historical realms. Repetition provokes self-reflexivity.

Artists, to be sure, have been critiquing the museum for decades. Andrea Fraser/Jane Castleton, Louise Lawler, and Fred Wilson, among others, immediately come to mind. It seems, however, that there is something specific about the contemporary ease of digital reproducibility that compels institutional self-consciousness; in other words, that this self-criticality is built into the curatorial conceit, and implicates one’s own museum rather than museums in general. (Another project in this vein was Triple Canopy’s installation, Pointing Machines, for the 2014 Whitney Biennial.) One often hears the caution that museums must fight to stay relevant alongside the rise of digital image proliferation—as if iPhone photos could become suitable substitutes for physical experience. Indeed, if visitor statistics are a valid metric, the opposite is true: the Metropolitan Museum announced a record for 2014 (6.3 million), a figure dwarfed by the Louvre’s 9.3 million. If this popularity is related to the accelerated rate of viewing—snap and run—that actually occurs in the gallery, it also seems to map onto a culture of the subsequent curating of those images on social media. A simple Internet search along these lines yields over half a million results: a whole cottage industry of suggestions and tips on how to present one’s best self on the web. That curating is the word attached to this organizational enterprise is not coincidental. Cognizant that the taking, editing, shuffling, and sharing of visual information—an act of replication and repetition par excellence, or what David Joselit calls “saturation through mass-circulation”—has become a crucial part of contemporary existence, museums are transforming their spaces into sites that invite audiences to think critically, with them, about the considered presentation of visual information and all of its underlying motivations. It is at this level that the museum calls on the hermeneutics of repetition—slyly, and by tipping its own hand—to slow us down.

Be First to Comment