Tucked amidst a spate of current shows featuring work in a particular vein of modernist painting—Stella, Olitski, Noland—Paul Barlow’s paintings, primarily of colorful frames, might seem little more than over-literal riffs on the medium’s ontology: canvas, stretcher bars, paint. And they are, undeniably, all those things, but close scrutiny reveals something else besides.

Blind Spots (on view January 14 – February 20, 2016) at Ana Cristea Gallery is a thirteen-work show of modestly-sized canvases by two painters: British artist Barlow and Norwegian artist Linne Urbye, both of whom are exhibiting in the United States for the first time. Urbye covers her canvases with repeating, often empty, abstract forms—chevrons, overlapping arcs, fleurs-de-lis, quarter-moons—in cool blues, greys, and whites. Often, her paint application discloses a prior composition below, laying bare the material’s twin function as both veil and window while simultaneously marking the support as a palimpsest of gestural maneuvers. These operations entail a certain resistance of vision on the part of the viewer, who must double down to visually excavate the logic of the marks beneath the uppermost layer. Through the interlocking arches, filled in to varying degrees in Untitled (12) (2015) we catch a glimpse of process, and wonder if we are seeing the work in an unfinished state. This transports the viewer from the space of the gallery to the space of the studio, a shift in register from the optics of viewing to the haptics of making. It is Barlow, however, who seizes most productively on the exhibition’s titular blindness as an operative term. This review, then, focuses primarily on his work.

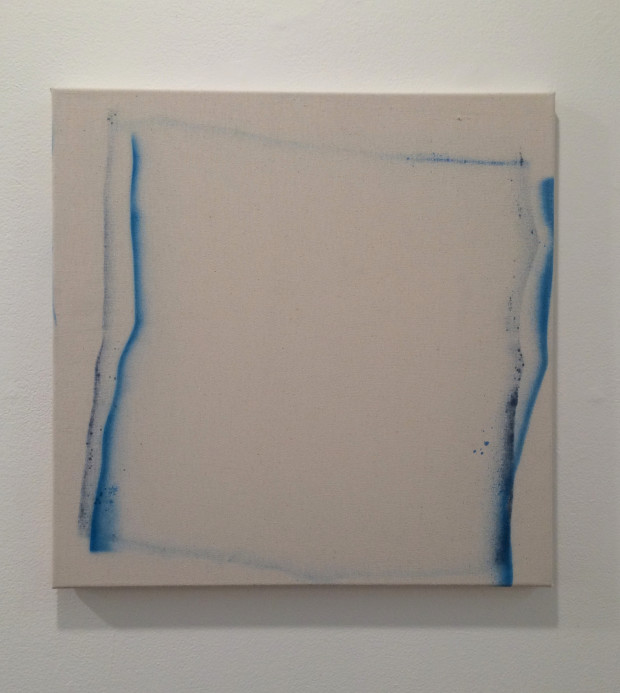

All of six of Barlow’s paintings on view at Ana Cristea engage the shape of the square as support. (The only canvas that isn’t a perfect square, Sink (Stretched Painting) (2015), derives its shape from two squares stacked atop each other.) In each case, bright hues hug the equilateral edges of the frame to varying degrees of crispness, recalling a hierarchy of pictorial viewing that regurgitates familiar discourses around the flatness and legibility of the picture plane. Yet, close examination of these works raises innumerable questions about process that defy these concerns, starting with the most basic: how were they painted? And, further, which side did Barlow paint? In Double Glazed (Stretched Painting) (2014), what initially reads as a painted frame emerges, after sustained looking, as a reverse indexical mark, like the auburn halo left on an album’s verso by an old photograph’s acidic trace. Indeed, Barlow paints, literally, from behind. With the canvas flipped over, he covers the stretcher bars and an adjacent margin of the canvas in an industrial, highly-pigmented spray paint. Where applied heavily enough, it bleeds through; each repetition provides another square form on the front. With each restretching, and the inevitably uneven surface tension resultant in the process, the rectilinear forms begin to wobble. Barlow, one suspects, also applies paint to the front, as evidenced by white passages that partly mask saturated areas beneath, or by the heavily abraded quality of the surface, as in Untitled (Stretched Painting 1) (2015), suggesting a vigorous scraping or brushing. To paint in this way is not a blinding, but it is a destabilizing of the artist’s access to vision in the physical act of mark-making.

All of this is vexingly hard to discern. We feel we can’t quite know how the works are made, because we intuit the main event is taking place—hiding—just beyond the reaches of our vision, amounting to something, we might even say, like sightlessness. The paintings stage a visual disjunction, refusing the beholder a stable, totalizing view of the whole. Unlike the instantaneous apprehension of a high modernist canvas, or even of a Judd sculpture, Barlow’s paintings spurn our visual and mental grasp. In this, they call to mind Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s description of embodied knowing: all human experience is lived in orientation to space, with a head above, feet below, and a front fundamentally different from a back it cannot see.

Barlow suggests that the colors used in his work stem from branding, sign-making, and peripheral vision—those hues just outside our line of sight. One recalls those pesky on-screen ads that flash, blindingly-hued, across a laptop while trying to read the news. With these paintings, peripheral vision redoubles as a kind of blindness, or at least an unconscious act of seeing. But it also proffers other means to probe the concept of periphery: where does the aesthetic experience begin or end? Is it contained in the object or contained in space? This brings to mind the way Robert Irwin recently described Stella’s copper paintings: that you might look more at the wall than at the painting (which he didn’t necessarily mean as a criticism). Barlow’s Stretched paintings reject such presentness. They argue that to look is not necessarily to understand.

Much contemporary painting is bound up with the concern of medium specificity. It is, after all, the material components that historically have made painting painting. Identifying a move away from Greenbergian credo toward the sublimation of other mediums and a flexibility in the materiality of painting’s signifiers, Lilly Lampe has recently argued that “what’s most vibrant in today’s painting is not about a break with time but a break with material, a break with two and three dimensionality into a fourth, an expansion into multiple art practices which could be called painting.” Barlow concomitantly distances his work from the impossibly narrow strictures of what Lampe calls the “lingering specter of Greenberg,” but at the level of discourse rather than at the level of medium. After all, “opticality” punctuates the critic’s writings with the force of few other words. It is this humanist take on vision that Barlow’s work questions. To be sure, Barlow isn’t the first to restretch or reverse a canvas (André Valensi and Steven Parrino come to mind, among others), but to do so now, while some of America’s top art museums squabble over abstract painting’s place, feels particularly apposite.

By word of mouth I heard that Cristea found Urbye’s work by paging through Instagram, and this strikes me exactly as the kind of seeing (or looking) that Barlow’s work resists. The anecdote is, perhaps improbably, a propitious way to make sense of the two artists’ work side by side. The Internet, and especially smartphone photographs of artworks, orients toward emphatic frontality, which, in this company, we might read as another kind of blindness. Rather than a rearguard call to anachronistic notions of painting, Barlow’s works might be understood instead as a call to challenge vision—that most prized of human faculties—in favor of a learning that is not about seeing or knowing but about the uncertainties in between.

Blind Spots: Paul Barlow and Linne Urbye is on view at Ana Cristea Gallery, 521 West 26th Street, New York, NY 10001, through February 20, 2016.

Be First to Comment