Contemporariness is, then, a singular relationship with one’s own time, which adheres to it and, at the same time, keeps a distance from it. More precisely, it is that relationship with time that adheres to it through a disjunction and an anachronism.[1]

– Giorgio Agamben

Although Sharon Hayes is a contemporary artist, reviewers of her work almost always discuss it in relation to American art and culture of the 1960s and ’70s. Critics such as Quinn Latimer and Paul David Young write of Hayes’s “plaintive missives [that] recalled songs from the ’60s and ’70s by Marvin Gaye and Nina Simone”[2] and that her art “speaks of a longing for the golden era of artistic and political radicalism of the late 1950s through the ’70s.”[3] During the Q&A following Hayes’s February 24, 2015 talk at the Institute of Fine Arts (part of the Artists at the Institute lecture series), Professor Robert Slifkin addressed this theme, asking the artist about any sense of nostalgia in her work: either for that period of American history, or for the radicality the era offered.

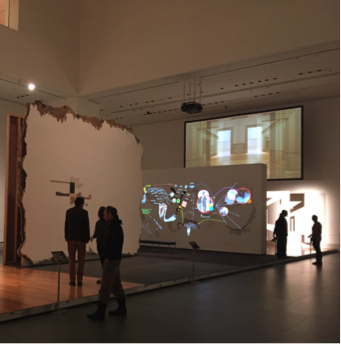

The question followed naturally from the artworks Hayes chose to highlight, which included Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA) Screeds #13, 16, 20 & 29 (2003), Everything Else Has Failed! Don’t You Think It’s Time for Love? (2007), Parole (2010), An Ear to a Sound in Our History (2011), and Ricerche: three (2013). Many of these were exhibited in her 2012 solo show at the Whitney Museum of American Art, and Hayes presented them as examples of engagement through video art. Of these five works, four explicitly reference or build upon art and events of the 1960s and ‘70s, from Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Comizi d’amore (1964) to Patty Hearst’s kidnapping by the Symbionese Liberation Army (1974). Hayes explained that, having been born in 1970, she had a “temporal” relation with that decade, but could not at the time process that moment’s politics and culture in which she finds such rich inspiration now. She told the audience that she does not mourn the loss of that era, but uses it as “the past that exists in the present,” or the “near past.” For Hayes, this “near past” has an unfinished relationship to our present moment, and sets the parameters for the questions and issues with which we still contend.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ExBCbpAHEpM

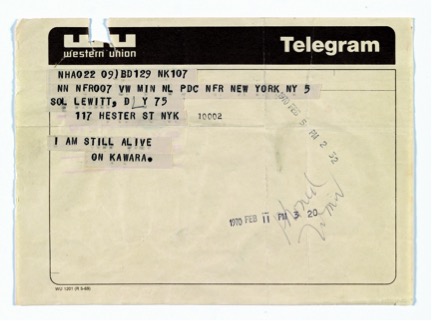

Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA) Screeds #13, 16, 20 & 29 (2003) was Hayes’s MFA work at UCLA. In it, she “re-speaks” the words of Patty Hearst on the videotapes released by the SLA, but without any of the fidelity of a reenactor, which is a purposeful distinction. Hayes explained to the audience that she finds the concept of “reenacting” problematic because such endeavors attempt to make whole the past, without its natural ruptures.[4] Instead, in the Screeds, the “notness” of the work is foregrounded: she is not Patty Hearst, it is not 1974, the camera crew is not the SLA. As Hayes stumbles through her partially memorized monologue, the audience eagerly jumps in to correct her mistakes, emphasizing the video’s disjunctures—not continuities—with the 1974 tapes. In 2006, Julia Bryan-Wilson astutely described Hayes’s approach as “investigations into the stutters of history, its uncanny reoccurrences and unexpected recyclings.”[5]

Hayes then screened Ricerche: three, a video of her interviewing Mount Holyoke students about gender- and sex-related topics, directed by Brooke O’Harra. I was surprised by Hayes’s blunt, direct, and leading questions, which contrasted so starkly with her usual careful speech, and often derailed the conversation or stymied the students. After the video, Hayes explained that the piece was formulated on director Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Comizi d’amore, and her interviewing style mimicked his, sometimes using the same questions. As did Pasolini, Hayes talked to the students in a group, “as their social selves,” and as they developed debates about feminism, identity politics, and trans issues, rifts formed: between the students who found “feminism” a welcoming label and those who didn’t, or those who saw sex as central to their identity and those who didn’t. During a lively and often provoking debate about current understandings of sex and gender, the transposition of Pasolini’s 1960s method and questions was often jarring and frustrating. And this fidelity to her source material displayed what Hayes called “disrupted time,” emphasizing, as in the Screeds, the distinctions (not the similarities) between the two contexts.