“The real issue is not to make another scientific toy, but how to humanize the technology and the electric medium.” – Nam June Paik, 1964

The staircase at the Asia Society Museum leads to an enlarged, transparent image of Nam June Paik sitting between two illuminated globes, contemplatively with chin in hand, wearing miniature televisions inset in a pair of eyeglasses. The image exemplifies the artist’s prescient thinking and his futuristic worldview wherein today’s technological advancements could exist. It is a fitting introduction to Nam June Paik: Becoming Robot (through January 4, 2015), the first solo exhibition of the artist’s work in New York in over a decade. The exhibition, designed by Clayton Vogel and curated by Michelle Yun, is an effort to broaden the understanding of Paik’s practice beyond his legacy as the originator of video art in the 1960s, and to situate his use of technology as a medium within the wider framework of late twentieth- and early twenty-first-century art.

Paik, born in Seoul in 1932, studied music and aesthetics at Tokyo University and went on to continue his musical studies in Germany, where he met visiting composer John Cage, who largely inspired Paik’s experimentation in avant-garde music and art. Moving to New York in 1964, Paik began working mainly on music-based live performances until his experimentation with televisions catalyzed the shift in his practice to object-based work.

The exhibition at the Asia Society spans the entirety of the museum’s two floors. Moving thematically through Paik’s oeuvre, the show begins with a section dedicated to Robot K-456, a twenty-channel radio-controlled robot created in 1964 and crafted with aluminum, wire, wood, electrical divide, foam material, and control-turn out. Based in human proportions, the biomorphic assemblage was programmed to walk and talk and was the subject of numerous performance-based projects. Presented on a simple screen set into the gallery wall (which successfully differentiates it from Paik’s own TV-based works) is a news account of First Accident of the Twenty-First Century, which was performed in 1982 on the occasion of the artist’s major exhibition at the Whitney Museum. The choreographed piece subjects the robot to a car accident while crossing Madison Avenue at 75th Street. As the robot falls to the ground in the footage, the beholder hears distressed shouts, proving that Paik has created a subject biomorphically familiar enough as to incite empathetic reactions. At a time when technology was advancing into a more pervasive component of daily life, humanizing the medium was Paik’s attempt at making it more approachable. The work’s reception in television media muddied the line between art and popular culture, and the piece itself reiterates Paik’s intention of manifesting the human condition through the mediums of science and technology.

Each section of the exhibition includes ephemera related to Paik’s projects: drawings for robot repairs, postcards, performance posters, notations, and working drawings. The materials give context to the realized works, and lend the exhibition the feel of a retrospective. The second section, TV as Medium, focuses on Paik’s collaborations with avant-garde cellist Charlotte Moorman (a relationship that would last until Moorman’s premature death in 1991), and works created with modified home electronics. Light Bikini for Opera Sextronique (1966/1975), a piece comprised of plastic netting with light bulbs on Plexiglas, cable, and a control box with toggle switches, demonstrates Paik’s pursuit to unite technology with the human body. Worn in a darkened auditorium during a 1967 cello concert, the bikini lights would intermittently flash as programmed by an offstage remote control. Similarly, in TV Bra for Living Sculpture (1969), which projected live TV, closed circuit footage, or prerecorded material activated by the optical waves from the cello, Moorman’s body was used as a means of humanizing technology. In its own room, a recreation of Paik’s tribute to Moorman at the 1993 Venice Biennale continues the theme; it is an homage replete with photographs and articles of her clothing. Showcasing the collaborative effort between Paik and Moorman makes explicit the collapsing distinction between human and technological “bodies,” which in turn weighs into the postmodern tradition of defiance toward boundaries.

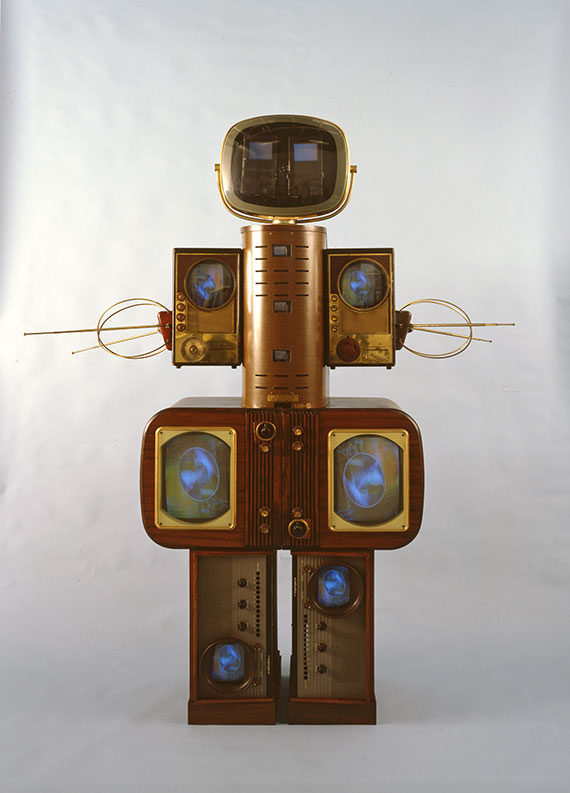

The next thematic section presents Paik’s return to robots in the 1980s. It includes a sampling of toy robots from Paik’s own personal collection of electronic equipment, as well as the larger-than-life Family of Robot series (1986) comprised in part by three single-channel video sculptures, Mother, Father, and Baby. The sculptures, made of stacked vintage TV sets, are installed alongside corresponding working drawings and an etching of a traditional Korean family structure (1984). Though stationary, each becomes anthropomorphized through its form and the movement of the looped, re-contextualized, and reformatted imagery playing on their many screens. In comparison to the dynamic robot family, the display case of Paik’s toy robot collection seems out of place, and with a lack of textual material explaining their function, one is left wondering what the artist’s relationship to the objects was.

The second floor galleries embody the theme of Transmissions, works that focus on Paik’s further experimentation with technology by altering video imagery through manipulation of the polarity of television cathode-ray tubes. In constantly looking toward technological advancement, he solidified a connection between art and mass media by using public broadcast systems in Boston and New York in the 1970s and 80s as a platform for presenting his work with magnetic picture interference. Golden Buddha (2005) explores the relationship between technology and human spirituality with a statue of a meditating Buddha contemplating his own image on-screen. Paik, himself a Buddhist, examines the interaction between eastern philosophy and western technology, as well as notions of what constitutes a past and a present in an age of technological immediacy. The work is underlined by instantaneous digital feedback when the viewer walks past the camera, interrupting the capture of the stationary Buddha’s image with a part of his or her own body.

The final component of the exhibition resides in a separate room with an interactive work, Three Camera Participation/Participation TV (1969/2001), which involves the closed-circuit technology seen in Golden Buddha. Playing with the idea of feedback, Paik subverts the distinction between receiver and transmitter with a video signal delivered directly through a cable link and projected onto a screen by three cameras that transmit the imagery with a nearly imperceptible time lapse. The work, essentially nonexistent without the viewer’s participation, proves Paik’s commitment to creating work that connects technology and the body.

The exhibition successfully underlines Paik’s contribution to avant-garde multimedia art and the contemporary use of technology, both as medium and network. Its installation at the Asia Society makes us consider the national identity of an artist who spent almost his entire working career in New York. We are left wondering if it is perhaps more fitting to consider him as belonging not to a particular place, but within the wider context of his practice, which exists amidst a complex, interconnected system, an unlimited world accessible through transmission. Paik expresses this notion with a drawing on a postcard entitled Invitation, Daadgalerie, Berlin (1984), in which two anthropomorphized televisions, one labeled “N.Y.” and another “Paris” are connected via a ringed planet marked with the year “’84.” A similar sentiment of interconnectedness is perhaps best described by Buckminster Fuller’s concept of our “fantastically real spaceship – our spherical Spaceship Earth.”[1] Fuller’s observation is contemporaneous with philosopher Marshall McLuhan’s writings that theorize media as an extension of the human body. He comments on the effects of particular media on humans, and the ways in which the adoption of new media consequently alters worldviews. While these concepts may seem natural today, in a society so saturated by technology that one’s cell phone seems literally to be an extension of his or her hand, McLuhan’s observations and Paik’s work demonstrate their impressive foresight for technology’s enduring ubiquity. Additionally, Paik’s involvement with distribution systems and his techno-utopian desire to integrate within a communicative mass medium devalue the need for cultural distinctions, and open up notions of connectedness to universal platforms.

“Nam June Paik: Becoming Robot” continues at Asia Society Museum through January 4, 2015.

[1] (R. Buckminster Fuller, Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1969), 46-7)

Be First to Comment