In lock step with a series of cross-country exhibitions showcasing the marginalized work of African American abstract painters (Sam Gilliam at David Kordansky and Norman Lewis at The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, to name two) The Studio Museum in Harlem has mounted a much needed, if small, monographic show titled, simply, Alma Thomas (on view July 14 – October 30, 2016). Alongside urgent contemporary debates spotlit by Black Lives Matter, such a recasting of (art) history challenges the hermeticism of academic discourse, art magazine glosses, and white-walled galleries; indeed, a New York Times feature story brought the trend to the attention of a broader public late last year. Timely, even-keeled, and sensitive without descending into hagiography, Alma Thomas presents the paintings of an artist who has emerged as a latter-day star, with her tangerine and carmine Mars Dust featured alongside Elizabeth Murray and Cy Twombly in the Whitney Museum’s inaugural downtown exhibition, and with a sunny mid-1960s circle painting on view in the White House dining room. As such, she exemplifies the latent power of repressed or silenced narratives.

Alma Thomas unfolds over the period of 1959 to 1976, roughly apace with the artist’s career. Born in Columbus, Georgia in 1891, Thomas’s family moved to Washington, D.C. in 1907 due to increasing racial tensions in the southern United States, and she remained in the capital until her death in 1978. Thomas’s commitment to education exceeded her own academic pursuits: after receiving a fine arts degree at Howard University, an MA at Columbia Teachers College, and an MFA at American University, she worked as an art teacher at Shaw Junior High School. Only upon retirement in 1960 did she turn her attention wholly to her own practice. Although almost entirely comprised of abstract work, the exhibition includes two early representational paintings, both titled Sketch for the March on Washington (c. 1964). In them, white rectangular forms atop a cool-hued mass of standing figures read almost as blunted mountains in an otherwise innocuous landscape. Only upon realizing that they are, instead, wordless protest posters do the paintings’ gravity and titular historical referent register.

This solemnity is offset by the joyful tone of the remaining works in the show, which addresses Thomas’s output in four thematic sections: Move to Abstraction, Earth, Mosaic, and Space. In the first of these, End of Autumn (1968) inaugurates what would become her signature style: short brushstrokes of varying lengths stacked one atop the other in linear sequences, packed tightly across the canvas. It is a tentative, uncertain painting, as if Thomas is testing out new ideas. In it, a field of fleshy peach daubs is interrupted by a hovering circular form, replete with rainbow-hued vertical stripes. More often than not, she seems to have begun her strokes from the top, pulling her paint downward. This is difficult to confirm, however, as closer scrutiny reveals that Thomas took a smaller brush loaded with a white acrylic (here as elsewhere of a slightly different tone from that of the primer) and painted over, and across, the multicolored upright bands. The overall effect is twofold: up close, it amounts to slighter, more bifurcated, and more jagged forms, while from further away it adds to the central motif a craquelure reaching inward from perimeter to center, like asymmetrical wheel spokes. Graphite lines peeking through (and sometimes on top of) Thomas’s clustered forms confirm that she laid down a preconceived compositional map. Breeze Rustling Through Fall Flowers (1968) demonstrates Thomas’s transposition of these same techniques onto a rectangular, rather than circular, format. It is one of many places in the exhibition where we feel we can see Thomas thinking via formal experimentation.

Save for the earliest four paintings on view, Thomas works in acrylic throughout. Given her longtime role as an arts educator, this puts me in mind of the jugs of like paint crammed in junior high classroom closets. Indeed her handling has nothing to do with that of her contemporaries, Washington Color Field painters like Thomas Downing, Sam Gilliam, and Kenneth Noland, who soaked diluted acrylics into unprimed cotton duck without ever touching brush to canvas. In so doing (according to their ringleader, the critic Clement Greenberg) painting could subvert illusionism’s unsavory implication of space and therefore absence (of the figure), opting instead for utter flatness and an attendant metaphysics of presence. Thomas’s marks, by contrast, sit resolutely atop a primed layer, the foremost among them cohering into a perforated curtain that appears to conceal another space behind. Her paintings reward close and sustained looking, but her vertical stripe works, especially, defy the “one-shot” motifs—polka dot sequences, pours, chevrons—of the artists listed above, instead edging closer to Gene Davis’s even-width stripe paintings. (In fact, my drawing such comparisons at all only underscores the extent to which Greenbergian discourse was erected for and around those painters exclusively, and reifies it in turn.) One senses that Thomas paid little heed to Color Field’s narrow strictures; her paintings could even be said to define themselves against such doctrines in a measured vote of defiance or non-participation.

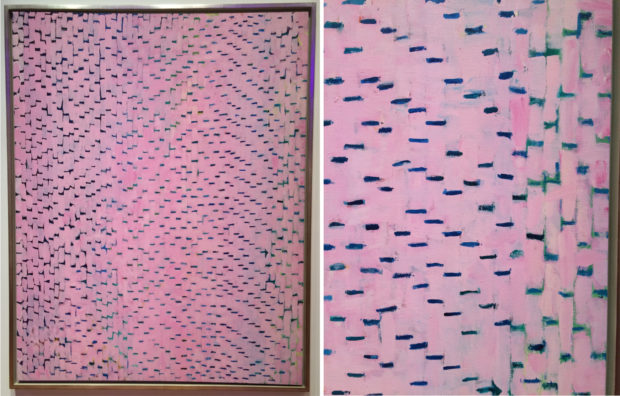

The early 1970s paintings included in the Studio Museum’s Earth section are the most masterful in the show. A gallery label informs us that Thomas first realized her commitment to abstraction while watching light shift through tree leaves in her garden, an anecdote that emboldens associative readings encouraged by oft-botanical titles but likewise frustrated by the works’ seeming nonobjectivity. In these pictures, such as the knockout Arboretum Presents White Dogwood (1972) or Cherry Blossom Symphony (1973), foreground and background swap roles: the shimmering veil of vertical brush marks becomes monochromatic (here, white and bubblegum pink, respectively), with the previously-vacant ground now full of chromatic variety, like a luminescent magical world only just hidden from view. Careful scrutiny of a columnar passage near Cherry Blossom Symphony’s right side demonstrates a nearly uniform application of pink, punctuated by short horizontal blues, here confounding the relationship between fore- and back-ground within a single painting. With brushstrokes in diagonally a- or de-scending sequences—so no adjacent brush stroke breaks at the same point as the one next to it, but instead toward its neighbor’s middle—these two paintings have the astonishing effect of an optical flicker or of vertical movement, like film strips reeling up or down at varying speeds. The late 1970s heralded a breaking apart of Thomas’s linearly-stacked forms into constellated zones interspersed with glyphs and squiggles, as in Scarlet Sage Dancing a Whirling Dervish (1976). These so-called Mosaic paintings are the latest in the show, truncated by her death in 1978.

A final, smaller section, Space, groups works resulting from Thomas’s fascination with air travel and NASA missions. Departing from the chronological sweep of the main gallery, this group dates between 1969 and 1972, and has the most interpretative potential. With titles like A Glimpse of Mars (1969), Snoopy Sees Earth Wrapped in Sunset (1970), Apollo 12 “Splash Down” (1970), and Starry Night and the Astronauts (1972), Thomas’s circle motifs obtain new valences, reading as planets seen from afar; her fragmented verticals as cratered soil crusts. Contemporaneous with the famed 1972 Blue Marble photograph of the earth seen from outer space, these paintings hint that Thomas was inspired by photographic documentation over and above her imaginative capacities alone. This is instructive because it validates realms of experience (like photography) otherwise not present in her works proper. Thomas’s interest in space travel, with its facility to decenter subjectivity and make room for new subject positions, strikes a chord with discourses of racial justice otherwise absent from the works. One wonders if Thomas’s yoking together via abstraction these two spheres of experience enabled her to bypass the demands placed on black artists for social content in their art, while not discounting it completely. (There is little irony in remembering that by 1969, the Studio Museum had declared abstraction irrelevant to black American life and essentially banned it from its galleries, insisting instead on figuration as a way to liberate audiences from the limited perspectives of white representational art.) In a brilliant and salutary move, Thomas shifts discursive registers, effectively speaking one language to make available another. All the while, her paintings maintain an optimism: a belief in the universal legibility of abstraction over figuration’s more limited range.

Throughout, Thomas’s paintings burst with ebullience, hopefulness, and verve. In 1970, Thomas proclaimed that “through color, I have sought to concentrate on beauty and happiness, rather than on man’s inhumanity to man.” She was a trailblazer through and through: the first person to graduate with a fine arts degree from Howard, and the first African American woman to receive a retrospective, in 1972, at the Whitney Museum. Her resurgence today comes when our country needs different voices—whether young or old—more than ever, a struggle that haunted Thomas, too. As she put it in 1972, “one of the things we couldn’t do was go into museums, let alone think of hanging our pictures there. My, times have changed. Just look at me now.”

Be First to Comment