One of the major advantages of studying at the Institute of Fine Arts at NYU is that our school is situated in New York City. A course that I’m currently taking with Helen Gould Sheppard Professor in the History of Art Edward J. Sullivan is held off-site every week in a different archive, gallery, or museum located in the city. There we have the opportunity to speak one-on-one with museum directors and curators. Being a part of these intimate conversations compelled me to attend the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s 2018 Career Insights event for college and university students (held on October 26) to learn more about being a curator of contemporary art at such a large and important museum only a block away from my classes at IFA.

There I met Kelly Baum, the Cynthia Hazen Polsky and Leon Polsky Curator of Contemporary Art at the Met. She graciously agreed to let me interview her about her role in organizing Odyssey: Jack Whitten Sculpture, 1963-2017, an exhibition that she co-curated with Katy Siegel, Senior Programming and Research Curator at the Baltimore Museum of Art and Thaw Chair in Modern American Art at Stony Brook University. Currently on view at the Met Breuer through December 2, 2018, the show is a retrospective of the late African-American artist Jack Whitten (1939–2018).

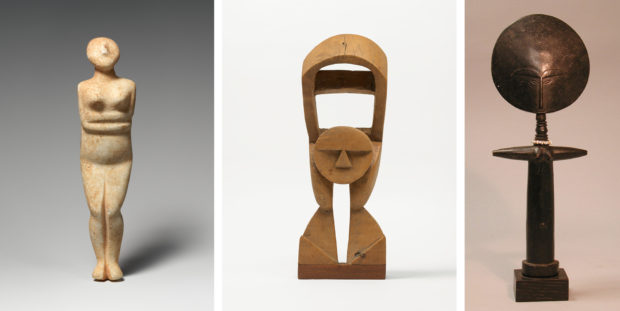

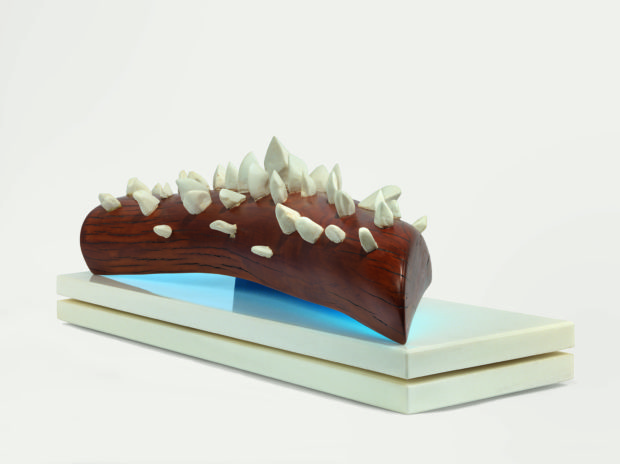

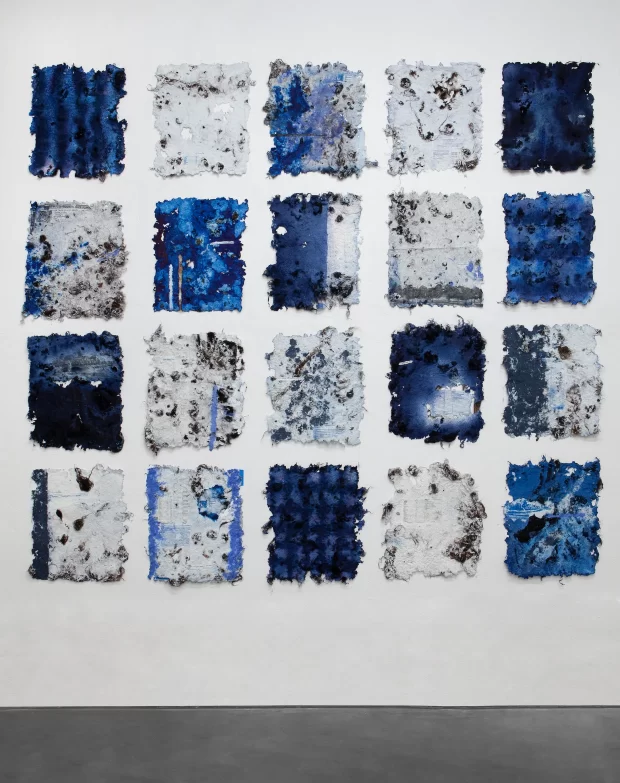

While looking at Whitten’s sculpture Door to Manhattan (1990), I began to imagine the odyssey he undertook when he came to New York City from Alabama in the 1960s, escaping the Jim Crow South. His arrival in New York opened the door for him to travel the world, engage with art of disparate cultures, and develop as an artist. While studying at Cooper Union, he dug into the African art archives at the Met and the Brooklyn Museum. Whitten was greatly influenced by African art, which he felt directly impacted the “DNA” of his sculptures. In the exhibition, Whitten’s sculptures and paintings are displayed next to objects from the Met’s collection of African art, as well as artifacts from Mycenaean, Minoan, and Cycladic cultures, showing how Whitten’s work is in dialogue with art from the ancient world. I spoke with Baum about how she, the artist, and her co-curator chose to contextualize Whitten’s work in the exhibition, and about her role more broadly as a curator at the Met.

Kasalina Nabakooza: Why did you become a curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art?

Kelly Baum: It was my choice to apply for the position, but it was the museum’s decision to offer me the job. I decided to apply for the job in 2015 for a few reasons: 1) I was very excited about the program that the new chairman of Modern and Contemporary Art, Sheena Wagstaff, was creating. It was experimental and global in scope. 2) I have always enjoyed curating modern and contemporary art in the context of broad, comprehensive collection’s like the Met’s. 3) I looked forward to the possibility of helping program the Met Breuer. 4) I was ready to move from a university art museum, with its relatively limited audience, to a large civic museum.

KN: Can you describe how your interaction with Jack Whitten influenced your curation of his exhibition at the Met Breuer?

KB: Jack supported the idea of exhibiting his sculptures, which he had never done before outside of his second home on Crete, at both the Baltimore Museum of Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Jack helped us assemble an archive of information about the sculptures and detailed their proper manner of installation. He also endorsed the inclusion of some of his paintings and a range of historical objects. Had Jack not passed away in January 2018, while the exhibition was still being finalized, especially the venue at the Met, he would have been even more intimately involved in its details.

KN: How does the breadth of Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection impact your ability to contextualize art within exhibitions?

KB: With an incredible breadth of collections comes an incredible breadth of not only curatorial expertise, but scientific and conservation expertise. I work with over 100 curators who belong to seventeen different departments. I relish the opportunity to learn from and collaborate with them, as I did in the Jack Whitten exhibition. Working with the curators of African art, Greek art, and American art, as well as their teams of collections specialists and conservators, we selected sixteen works of art from the Met’s collection to appear alongside Whitten’s sculptures. These former represent the art historical DNA for the latter. Important too is the fact that Jack drew inspiration for his paintings and sculptures directly from the Met’s collection.

William W. Brill, 1963

KN: How do you collaborate with other curators and artists to develop exhibitions?

KB: There are many ways to co-curate an exhibition. In the case of Odyssey, my co-curator and I worked with some of the same material—specifically the 40 sculptures and the 11 Black Monolith paintings—but presented them in very different ways. I also added some additional paintings and utilized historical objects that belonged to the Met. Other times, I have worked with another individual to conceptualize an exhibition from the ground-up, with every object being chosen together.

KN: Is collaboration an essential skill for curators?

KB: Yes! Curators must be able and willing to collaborate, and to collaborate with a wide range of individuals, from fundraisers and educators to technicians, artists, framers, conservators, mount-makers, and graphic and exhibition designers. One needs empathy and flexibility in order to collaborate successfully. Virtually everything I do for the museum is a collaborative venture. This stems from the nature of the curator’s role: curators serve the institutions for which they work. No decision is made in a vacuum, without the input and consent of many others, especially the department chair, the deputy directors, the director, and the president.

KN: Can you describe the writing your research assistant did on the legacy of curator Lowery Stokes Sims at the Met?

KB: My summer intern, Taylor Montague, researched Lowery’s tenure at the Met, her background, her political activism, especially in the 1960s, and the works of art whose acquisition she championed over the course of her long career at the museum.

KN: Are there primary materials available regarding Sims’ development as a curator at the Watson Library in the Met?

KB: There are currently no primary documents related to Lowery in the Met’s archives. (Our own research was conducted in the curatorial files and through the library’s databases.) However, the Archives of American Art is currently editing an oral history interview with Lowery. It should be available in the coming months.

KN: What is on the horizon for collaboration between NYU and the Met?

KB: The Met has revamped its Curatorial Practice Program, and NYU belongs to our consortium of participating universities and colleges. The Met had a close working relationship with NYU for decades.

KN: What is the most satisfying part of your job as a curator at the Met?

KB: One of the most satisfying aspects of my job is the degree of physical access I’m granted to incredible works of art on a daily basis. It is a true privilege. And with it comes a special kind of knowledge. I also love installing works of art: it is a way of telling stories in space, with objects, for the benefit of the public.

KN: Are there other curators that you consider to have been ahead of their time or are presently pushing the boundaries of what is possible?

KB: There are incredible curators working across the globe, but I’m most familiar with those based in the US. I always love seeing what Rita Gonzalez, Connie Butler, and Anne Ellegood are curating in LA, what Naomi Beckwith is doing in Chicago, what Valerie Cassel Oliver is up to in Richmond, and what Eva Respini is organizing for the ICA Boston. Today I just learned about a new space downtown called Assembly Room that provides opportunities for female curators to collaborate on curatorial projects—I find this very exciting, likewise Project Row Houses in Houston, which has a ground-breaking curatorial agenda that focuses on the local community and social justice. And in New York there are incredible curators at every institution, big and small—including the Met. I’m lucky to work here with nine outstanding curators of modern and contemporary art.

KN: What have been your most challenging and rewarding exhibitions throughout your career?

KB: The most rewarding exhibitions of my career were Nobody’s Property: Art, Land, Space, 2000-2010 and New Jersey as Nonsite, organized for the Princeton University Art Museum, as well as Delirious: Art at the Limits of Reason, 1950-1980 and Odyssey: Jack Whitten Sculpture, 1963-2010, both for the Met. All of these involved taking intellectual and art historical risks. Some of these shows were also among the most challenging of my career, either for logistical or political reasons. I think it’s important to curate exhibitions that engage pressing and provocative political subjects, but when you do so, you open yourself up for a great deal of push-back.

KN: I’m beyond thrilled that you agreed to be my mentor as I study at the IFA. Why is mentorship important to you?

KB: As I’ve grown as a professional, and as I meet with more and more undergraduate and graduate students, I’ve come to realize the importance of mentorship. It’s not in my official job description, but I still consider mentoring students an integral part of what I do. I’ve had a few great mentors over the last 20 years, some from the museum world and some from academia, and their support has made a world of difference to my own development. Every student deserves an advocate. This becomes even more important as the job market grows increasingly competitive. Mentorship is also an important way of making the art world, which tends to operate like an insider’s club, more inclusive and diverse.

Be First to Comment