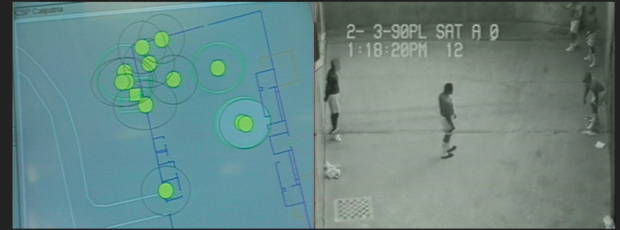

Cover image: Julia Scher, Vigilance, 1991. Photograph of exhibition. Image courtesy juliascher.com.

Since the revelations of Edward Snowden in 2013, it has become impossible to avoid the topic of government spying, data privacy and mass surveillance. It’s in the news, on our screens, and affects how we think about and engage with today’s digital world. But what does surveillance mean for art and the practice of art history? Given its reliance on image-making and other image-capture technologies, does surveillance affect how we understand the meaning and function of images—today and in the past? As these technologies become increasingly ubiquitous, seamlessly integrating into the environments we inhabit without notice, do we interact with images in a different way than before? Has the nature of images themselves transformed since they’ve been called upon not only to represent things, but to perform actions in the world—becoming “operational images”?

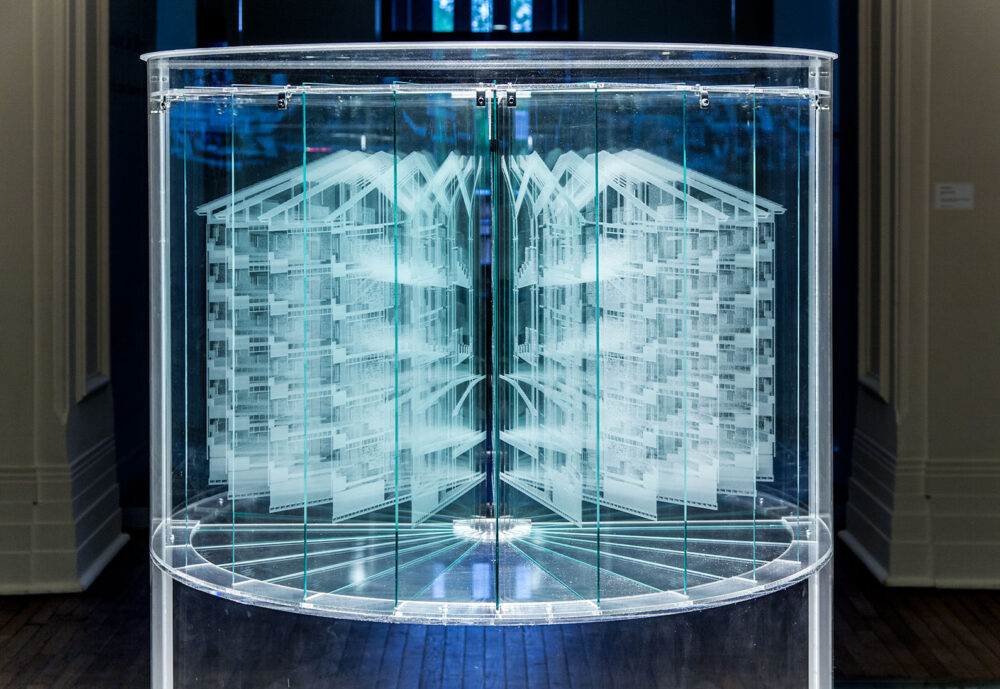

Artists such as Harun Farocki, Julia Scher, Jonas Dahlberg, Aernout Mik, Hito Steyerl, Trevor Paglen, David Spriggs, and James Bridle have in various ways engaged the perceptual, technical, and social problems embedded in surveillance through their work in film, video, installation, and photography. Some of these artists draw on the historical and theoretical work of Michel Foucault, who popularized Jeremy Bentham’s late eighteenth-century “panopticon,” a circular prison design organized around a central watchtower. David Spriggs’s 2014 work, Logic of Control, for example, invokes this legacy by staging Bentham’s prison in a semi-circular display of engraved glass sheets. What Logic of Control brings to the fore is the way that surveillance is a question of power over vision and control over access to it. In Bentham’s original design this dynamic of power is arranged by the architecture and the lines of sight it imposes and prohibits. The prisoner’s confinement in a cell whose barred door faces the interior guard tower limits the surveilled’s ability to see, while at the same time making him or her visible to the surveillant at all times.

The generalization of this inspection-function across nineteenth-century institutions—the school, the army, the factory—is the subject of Foucault’s work and the source of many artists’ engagement with a long history of surveillance with roots in the industrial revolution and Western modernization. Exploring this long view of surveillance, these artists interrogate the ways that the progress of technology still variously furthers the logic of modernization inaugurated in the nineteenth century and its need for the elaboration of more and more refined “systems for the management and control of human beings,” as art historian Jonathan Crary has claimed [1].

In what ways, then, does surveillance affect the modes of visibility of society—the kinds of images it produces and the uses it has for them? How does contemporary mass surveillance build upon and/or depart from these uses? From the Romantics to the present day, art’s capacity to grapple with the problem of modernization and the modes of visibility and power it brings about is a continuing legacy of nineteenth- and twentieth-century art. Contemporary artists have responded in turn to recent developments.

It may be that many of the concepts that art historians use to talk about images are not appropriate to the characterization of images and their function in contemporary society. Hito Steyerl, for instance, has identified a predominant shift away from pictures with a vanishing horizon, organized according to traditional linear perspective, to pictures of vertical or aerial perspective used by a wide variety of images today—from Google Maps to attack drones.

Trevor Paglen has similarly challenged traditional concepts coming from photography theory and visual culture like Guy Debord’s “spectacle” and Roland Barthes’s semiotics. For Paglen these models don’t quite capture the current use of images which is no longer tied to problems of objectivity, interpretation, or indexicality that once dominated the discourses of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Rather, Paglen suggests, today’s images are designed to “do” something, to actively perform or enact a function rather than to classify or confirm.

For both Steyerl and Paglen, rethinking the role that images play in the age of mass surveillance and the ways that art can be brought to represent it also means creating new theoretical models capable of articulating and thinking about the problem. Indeed, for art history to come to terms with this transformation of images in today’s surveillance societies—and the deployment of visibility it entails—would be for it to align itself with one of the major political tasks of our time: to understand the meaning of surveillance, what it does, what it has the ability to do, and in what ways it can be resisted.

Footnotes:

[1] Jonathan Crary, 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep (New York: Verso, 2013), 36.

Be First to Comment