On December 2, 2014, University of Maryland Professor Joshua Shannon delivered a lecture entitled “Photorealism: A History of Surfaces” as part of the Institute of Fine Art’s Daniel H. Silberberg Lecture Series. (A recording of his talk can be viewed here.) The theme of the Silberberg lecture series this year is “failure,” and Professor Shannon’s presentation on photorealism took the failure of credibility suffered by humanist painting in the late twentieth century as a point of departure. IFA Ph.D. Candidate Claire Brandon interviewed Professor Shannon following the lecture.

In the beginning of your lecture, you mentioned 1968 as the starting point for your study. What was happening with the practice of photorealism during that moment? How do you see it as marking such a major shift in painting?

Photorealism made a rather sudden appearance in painting in 1967-68. Most of the photorealists had been making other kinds of realist painting in the years just before then, but it is amazing to see how suddenly—and simultaneously—many of them began to make paintings that acknowledged, even exaggerated, the fact that that they were based on photographs. This struck me as a fact needing some historical explanation.

Why have you chosen to focus on Robert Bechtle? How can his work be differentiated from the other photorealists you brought up, such as Chuck Close, Richard Estes, and Ralph Goings?

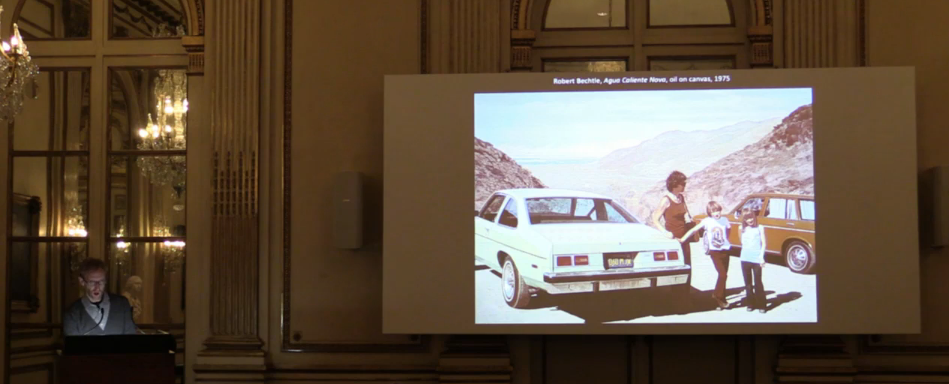

I just think Bechtle made many of the richest and most revealing paintings. The photorealists are united by the fact that they all make clear that they have painted from photographs, but the kinds of photographs they work from are actually quite diverse. While Estes, for example, uses urban architectural photography and Close uses portrait photographs, Bechtle works from snapshots. His paintings are deliberately exploring amateur photography, even mediocre amateur photography. Bechtle is interested not so much in precision or in dryness as he is in posing. His paintings are about self-presentation, and about what counts as a good or meaningful picture. As such, Bechtle has his fingers on many of the most important problems in visual representation over the past several decades. We have so much to learn from his paintings.