The Usable Past: “The concept that a self-conscious examination of historical figures, moments, and symbols can shape current and future political formation.”[1]

This is how the Whitney defines the title of one of five galleries in their ongoing permanent collection exhibition An Incomplete History of Protest. The works in the gallery present memory and nostalgia as both powerful and yet often insufficient vehicles to re-experience the past. Sharing tropes of obfuscation and anonymity, the works materialize the incomplete nature of memory and documentation.

Annette Lemieux’s painting Black Mass (1991), in which she replaces the protest signs in a civil rights march with black, empty squares, hangs across the room from Glenn Ligon’s Untitled (Speech/Crowd) #2, a photograph of the Million Man March which Ligon has blurred and layered with coal dust. These works recall acts of censorship and evoke the fading hope of social change in a world where battles for civil rights must be repeatedly fought. However, the works in the exhibition that truly express the concept of “the usable past” are those which feature the museum as their main subject.

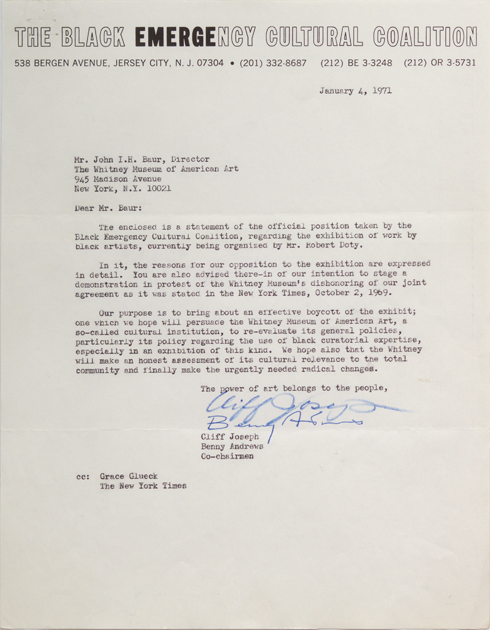

Lining the walls of the museum’s new Meatpacking building, a multiplicity of letters of protest written to the Whitney by artists and organizations related to the institution emerge from the Whitney’s archives. In a letter from 1971 addressed to former director John I.H. Baur, the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition announced their opposition to the 1971 exhibition Black Artists in America and declared their plans to demonstrate on the museum’s premises. Their initial discontent stemmed from the Whitney’s seemingly empty promise to hire and consult with black art leaders for the curating of the show. The BECC’s correspondence with the Whitney attests to the fact that the institution has dealt with issues surrounding the cultural agency of marginalized groups in an art context. Alongside this letter, dozens of other requests from artists implore the museum to remove their work as acts of protest or solidarity during moments of political unrest, and urge the museum to take a stance on current socio-political debates.