All photographs date from the early 1960s through 1966.

In 1990, the South African court justice Albie Sachs famously penned an essay called “Preparing Ourselves For Freedom” in which he argued for a return to beauty in the arts, and an expansion of creativity beyond the decades of revolutionary cultural work aimed at supporting the anti-apartheid struggle. While the lifelong activist knew firsthand that political engagement had long been a matter of survival, he asserted that the repeated imagery of “fists, spears, and guns” might limit the creative imagination of the new South Africa, that “the range of themes is narrowed down so much that all that is funny or curious or genuinely tragic in the world is extruded. Ambiguity and contradiction are completely shut out.”[1] Be that as it may, there will always be those rare, inspired cases in which the political and the beautiful need not be mutually exclusive, where complexity and ambivalence are found in the most seemingly black-and-white circumstances. The work of South African photojournalist Ernest Cole (1940-1990) offers one such example. His work betrays a deep commitment to both social and aesthetic engagement, which come together in a stunning portfolio of photographs that documents life under apartheid and pays homage to the persistence of humanity through struggle.

Ernest Cole: Photographer, organized by the Hasselblad Foundation and currently on view at NYU’s Grey Art Gallery through December 6th, is the first museum retrospective of Ernest Cole’s work, and one that is long overdue. The artist risked his life and ultimately sacrificed his citizenship in order to produce his seminal photobook House of Bondage, which remains one of the most visually powerful and politically incisive documents of the apartheid era.

Cole considered it his life’s work to chronicle the black experience from every angle: public and private, at work and at home, and inclusive of the perspectives of men, women, children, and families. He envisioned his target audiences to be foreigners – Europeans and Americans – both in the hopes of revealing the horrors of apartheid to the outside world, and in full knowing that he would never be able to distribute his work domestically (even today, the book is less known in South Africa than it is in the West, having only been published in New York and London in 1967). Across this presentation of over one hundred images, shot throughout the 1960s, we bear witness to not only the gross indignities inflicted on black South Africans by the apartheid system, but also a collection of more intimate, everyday moments that humanize and honor Cole’s subjects.

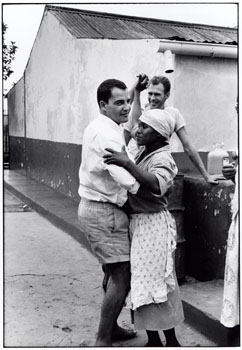

The political heavy-hitters of his oeuvre are displayed at the entrance to the exhibition – including a striking image of miners lined up for medical examination, arguably one of his most famous shots – while later in the installation we come to witness vignettes that speak to a wider range of experiences. Near the back wall of the Gallery hang photographs of impromptu dances between whites and blacks, both in suburban driveways in broad daylight and within the underground spaces of shebeens, or illegal nightclubs, where South Africans often socialized across racial boundaries. In his shots of domestic workers caring for the children of their white employers, Cole manages to capture an ambiguous emotional spectrum in the eyes of his subjects, who express maternal love for these children as well as contempt for the system that will soon turn them against one another.

While his photographs narrate a collective story of resistance, many also engage with personal experiences that shaped the artist’s own life. Cole was born in 1940 in the black freehold township of Eesterust, but his family was later relocated to a town called Mamelodi in 1960 under the Group Areas Act, when the entire neighborhood was bulldozed within the space of a few hours. One series of images on view relates to this traumatic experience, documenting the razing of a township community of two thousand residents. In one, we face a looming bulldozer pushing the remnants of a wall into the foreground, as dust rises from the debris at the bottom edge of the picture; elsewhere, Cole expands his frame to span a sprawling tent city that became home to thousands of displaced families who had been, as he explains, “uprooted before the new township was ready for them.”[2]

Another haunting suite of images documents the inhumane conditions of black hospitals, in which patients huddle together on the floor or lay on soiled mattresses in rooms filled well beyond capacity. One photograph shows a patient tending to his head bandage; behind him, a dark hospital corridor recedes sharply towards the back wall. The low lighting and severe compositional angles create a level of suspense that rivals Lewis Hine’s infamous photographs of child factory workers. While undeniably impactful as a documentary series, these photographs, too, engage with Cole’s biography. He had once been treated at Baragwanath, the hospital depicted in this series, after a motorcycle accident that fractured his knees. As he told his colleague Struan Robertson, he waited in the “dumping ward” for nearly a month, and was discharged with sustaining injuries to his joints that never fully healed. At Baragwanath, Cole witnessed “the appalling state of black health-care,”[3] and later wove this personal experience into a larger narrative of life under apartheid.

Several of the photographs on view at the Grey were included in House of Bondage; However, Cole was known to have felt dissatisfied with the cropping and formatting of images that occurred in the process of its publication, resulting, in his view, in their complete loss of integrity. The current exhibition offers an opportunity to see his prints exactly as the artist would have intended: unaltered, uncropped, and faithful to the circumstances in which each was taken, whether carefully composed or shot clandestinely through his coat pocket or a paper bag. His insistence on maintaining the aesthetic integrity of each negative is a testament not only to his artistic philosophy – which he owed to a careful study of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s photobook People of Moscow, lent to him by a friend – but also to his rare ability to capture the elusive ‘decisive moment’ under such trying circumstances.

For instance, one photograph depicts the chaos of boarding blacks-only trains, whose destinations and schedules were often unmarked or unannounced, resulting in last-minute confusion as passengers were forced to dash across the tracks. The image is divided by a straight vertical axis running from top to bottom edge, just left of center, which separates the bright concrete platform from the gravel-filled track yard. Converging at a single point that intersects with this vertical seam, a series of dramatic orthagonals designate a pair of steel tracks and a train parked several yards from the boarding platform. Men race across empty tracks; Cole captured one figure mid-leap, his right hand still gripping the platform’s edge as he thrust his body forward toward the train. Fields of light and shadow alternate in almost perfect sequence around the radial axis created by that single recessional point. This is one of the most brilliant and poetic pictorial compositions in the entire exhibition, yet the image also serves to document the difficulties faced by black South Africans in light of the inhumane conditions of their segregated amenities.

Directly above this image, the Grey has hung another that documents the interior of the traincar, creating a kind of “before and after” study of this hectic commute. Yet the two could not be more stylistically opposed: here, everything is compressed into the foreground of the image, with figural subjects tightly packed in the lower and middle registers, their faces reflecting the flash of Cole’s camera in a darkly lit, overcrowded car. The ceiling hovers just above the heads of commuters and the entire space is foreshortened, resulting in a claustrophobic pictorial field. The contrast between these images highlights Cole’s versatility more than it does inconsistency, as well as his great amount of dedication.

Cole’s colleagues describe him as having been hardworking and determined, but eventually his work began to attract unwanted attention from the police. After he shot a series of photographs documenting gang muggings in Pretoria, he was accused of taking part in the crime, then later asked to become an accomplice in the arrest. Caught between the potential repercussions of either betraying his subjects or disobeying the police, he grew paranoid and sought to leave the country altogether. He was able to secure a passport and left South Africa in 1966, moving between Europe and the United States for several years; once abroad, he was finally able to pursue the publication of House of Bondage.

Ernest Cole: Photographer stages Cole as an artist who remained aesthetically innovative while giving primacy to the social content of his work. In opening his lens to the complex emotional lives of fellow South Africans, and in telling stories of love, loss, and the persistence of culture within a repressive society, his work serves as a timely reminder for viewers to search for a common sense of humanity and beauty even in the most difficult of times.

[1] Albie Sachs, “Preparing Ourselves For Freedom: Culture and the ANC Constitutional Guidelines,” TDR (35:1, Spring 1991): 187.

[2] From the image caption for the exhibition, itself pulled from the original publication of House of Bondage, 1967.

[3] Struan Robertson, “Ernest Cole in the House of Bondage” in Ernest Cole: Photographer, (Göttingen: Steidl and Hasselblad Foundation, 2010): 25

Be First to Comment