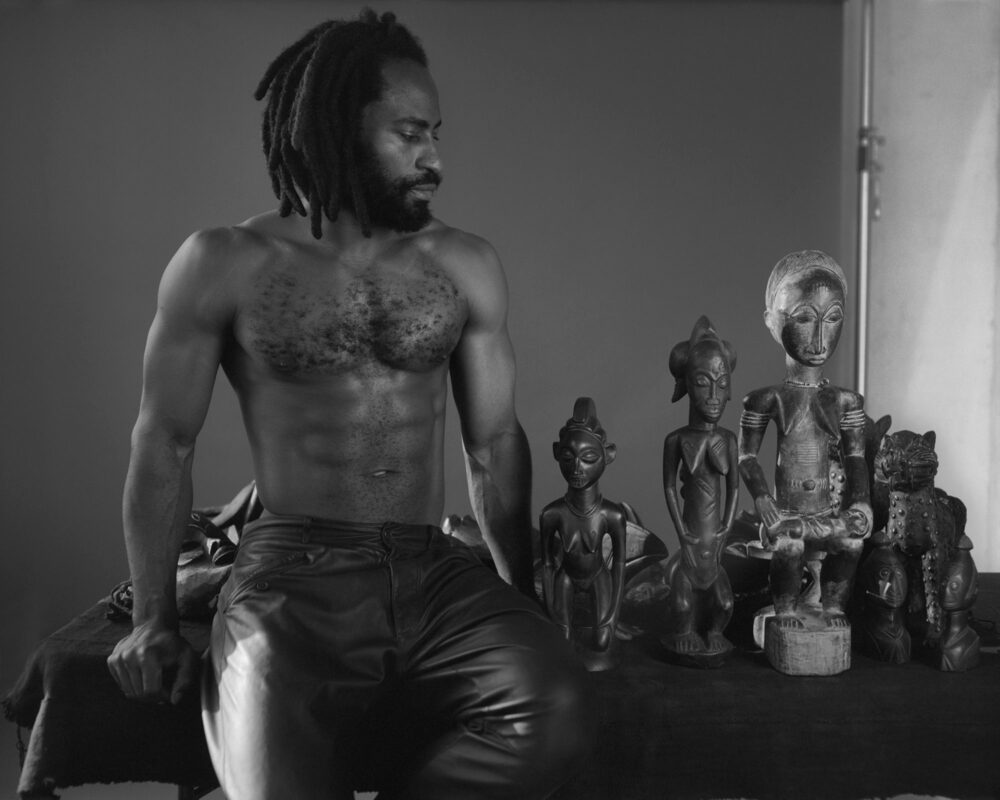

A sidelong glance reveals as much as a direct gaze—which Hans Holbein the Younger humorously demonstrated in The Ambassadors (1533) by depicting a skull at… Continue Reading John Edmonds Gives Us Some Serious Side Eye

Posts published in “African Art”

When visitors step into the Whitney’s first-floor gallery, which currently houses Toyin Ojih Odutola: To Wander Determined, they risk forgetting that they are standing in a museum. There is a softness to the space that distances it from the rest of the building, its warm lighting and the pink color of the walls evoking a feeling of intimacy that is both inviting and disorienting. A proclamation near the entrance, signed by artist Toyin Ojih Odutola in her role as “Deputy Private Secretary,” alerts viewers that the sixteen arresting works spread throughout the gallery are from the private collections of two aristocratic Nigerian families, the UmuEze Amara and Obafemi, connected through the marriage of the Marquess of UmuEze Amara, TMH Jideofor Emeka, and his husband, Lord Temitope Omodele. With this information, the intimate atmosphere is given context: it feels as if visitors have been transported to a private, family portrait gallery.

If not for the aforementioned, rather official wall text bearing the families’ crests, viewers would not know that Ojih Odutola’s subjects were of such prestigious social standing. Even armed with this knowledge, they are confronted with an incomplete narrative, left to question the identities of the elaborately fashioned figures in each portrait. No names are provided, nor are there any indications of the lineage from which each subject descends. What remains in their absence is a vague understanding that the subjects are related, as well as a desire to know how. Perhaps in other circumstances it would not occur to visitors to scrutinize the figures presented to them, but the context both provided and omitted by the artist’s proclamation incites a curiosity that may never fully be satisfied. This is the challenge that Ojih Odutola sets forth for her audience.

Okwui Enwezor gave his first talk of the Kirk Varnedoe Lecture Series on Tuesday, February 21, called “Setting the Stage: From Postcolonial Utopia to Postcolonial Realism.” His series is titled “Episodes in Contemporary African Art,” which foreshadows a methodology centered not on grand narratives but on case studies that can enliven our understanding of an emerging field behind which Enwezor himself has been the driving force.

Today, we are all well aware that contemporary art has become a “global” phenomenon; from Chelsea to Venice we confront cutting-edge works by non-Western artists. William Kentridge, El Anatsui, Yinka Shonibare MBE, and Ghada Amer have all held significant retrospectives in recent years, in addition to countless others featured in group exhibitions. However, the “globalization” of contemporary art didn’t happen overnight, and as art historians we still lack a comprehensive understanding of the transition from “traditional” to “contemporary” in many parts of the world, especially Africa. Hence, Enwezor’s inaugural lecture, aptly titled “Setting the Stage,” offered a timeline against which the emergence of contemporary African art can be set.

Enwezor premised his talk around an inversion of the dictum that begins E.H. Gombrich’s The Story of Art—“There is no art as such, there are only artists”—proposing that when it comes to Western reception of African art, the reverse is often assumed; namely, that there are no African artists as such, only African art. African art has often been associated with ritual and collective production, in opposition to Western art history’s preoccupation with artistic genius, the “Master,” and individual oeuvres.